Updated: 1 October 2024

Welcome to the night skies of

Spring,

featuring

Carina, Crux, Centaurus, Virgo, Boötes, Hercules, Scorpius,

Ophiuchus, Sagittarius, Capricornus, Aquarius, Grus, Aquila, Lyra, Saturn and Jupiter

Note: To read this webpage with mobile phones or tablets, please use them

in landscape format, i.e. the long screen axis should be horizontal.

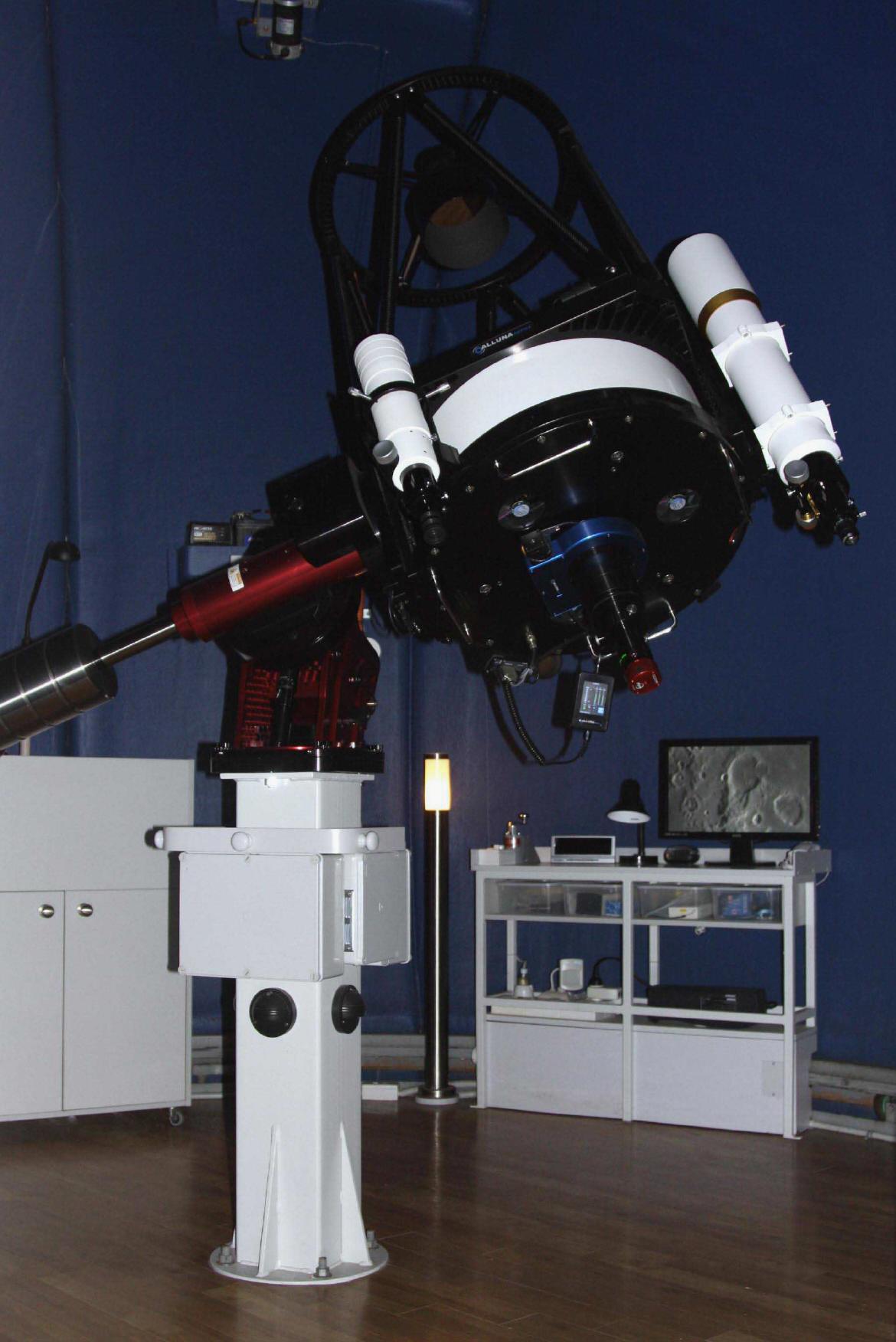

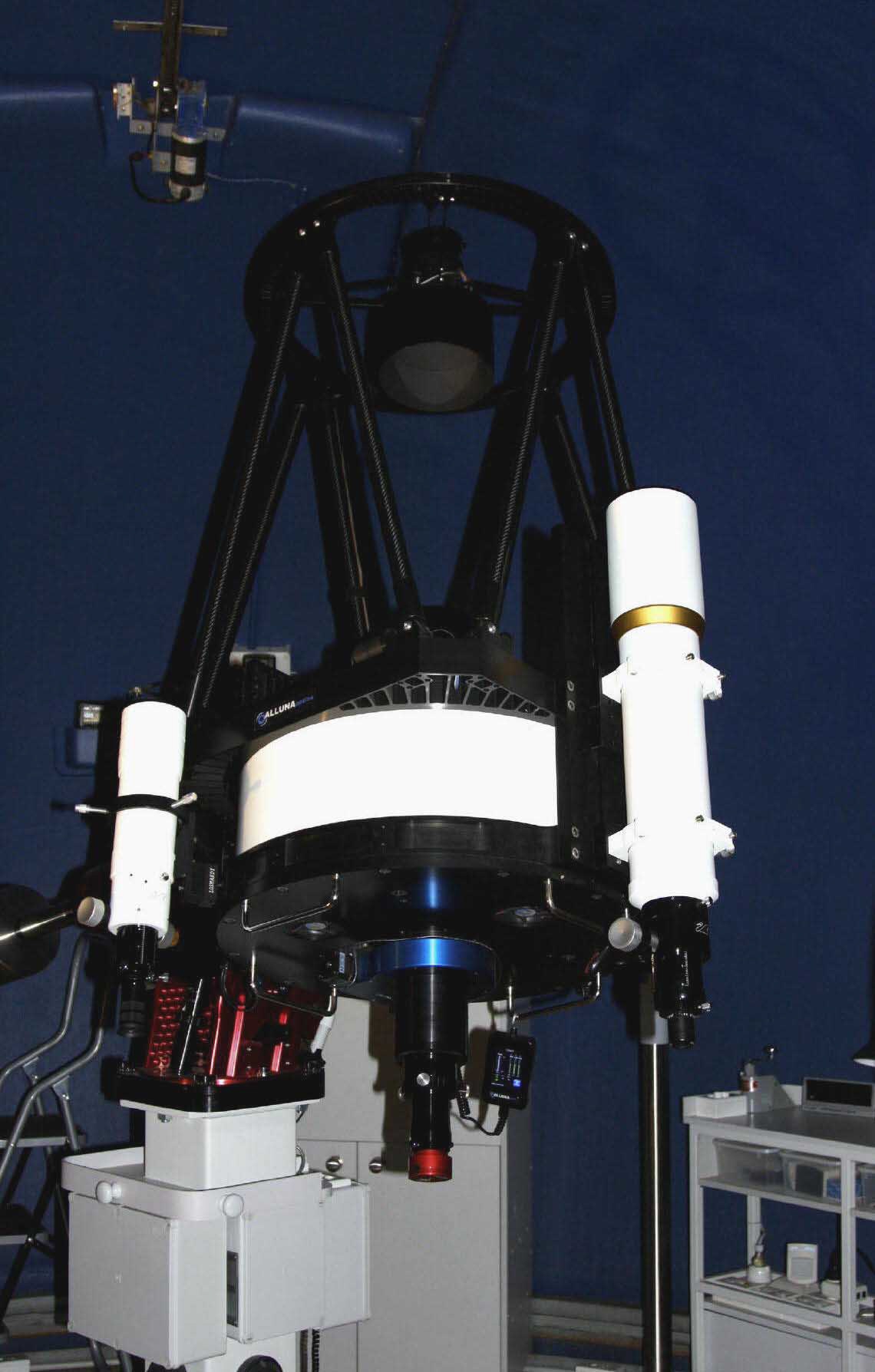

The Alluna RC-20 Ritchey Chrétien telescope was installed in March, 2016.

The 20-inch telescope is able to locate and track any sky object (including Earth satellites and the International Space Station) with software called TheSkyX Professional, into which is embedded a unique T-Point model created for our site with the telescope itself.

Explanatory Notes:

Rise and

set times are given for the theoretical horizon, which is a flat horizon all the

way round the compass, with no mountains, hills, trees or buildings to obscure

the view. Observers will have to make allowance for their own actual horizon.

Transient phenomena are provided for the current month

and the next. Geocentric phenomena are calculated as if the Earth were fixed in

space as the ancient Greeks believed. This viewpoint is useful, as otherwise

rising and setting times would be meaningless. In the list of geocentric events,

the nearer object is given first.

When a planet is referred to as ‘stationary’, it means

that its movement across the stellar background appears to have ceased, not that

the planet itself has stopped. With inferior planets (those inside the Earth’s

orbit, Mercury and Venus), this is caused by the planet heading either directly

towards or directly away from the Earth. With superior planets (Mars out to

Pluto), this phenomenon is caused by the planet either beginning or ending its

retrograde loop due to the Earth’s overtaking it.

Apogee and perigee: Maximum and minimum distances of the

Moon or artificial satellite from the Earth.

Aphelion and perihelion: Maximum and minimum distances of a

planet, asteroid or comet from the Sun.

Eclipses always occur in pairs, a lunar and a solar but not necessarily in that

order, two weeks apart.

The meridian is a semicircle starting from a point on the horizon that is

exactly due north from the observer, and arching up into the sky to the zenith

and continuing down to a point on the horizon that is exactly due south. On the

way down it passes through the South Celestial Pole which is 26.6 degrees above

the horizon at Nambour. The elevation of the South Celestial Pole is exactly the

same as the observer's latitude, e.g. from Cairns it is 16.9 degrees above the

horizon, and from Melbourne it is 37.8 degrees. The Earth's axis points to this

point in the sky in the southern hemisphere, and to an equivalent point in the

northern hemisphere, near the star Polaris, which from Australia is always below

the northern horizon.

All astronomical objects rise until they reach the meridian, then they begin to

set. The act of crossing or 'transitting' the meridian is called 'culmination'.

Objects closer to the South Celestial Pole than its altitude above the southern

horizon do not rise or set, but are always above the horizon, constantly

circling once each sidereal day. They are called 'circumpolar'. A

handspan at arm's length with fingers spread covers an angle of approximately 18

- 20 degrees. Your closed fist at arm's length is 10 degrees across. The tip of

your index finger at arm's length is 1 degree across. These figures are constant

for most people, whatever their age. The Southern Cross is 6 degrees high and 4

degrees wide, and Orion's Belt is 2.7 degrees long. The Sun and Moon average

half-a-degree (30 arcminutes) across.

mv = visual magnitude or brightness. Magnitude 1 stars are very

bright, magnitude 2 less so, and magnitude 6 stars are so faint that the unaided

eye can only just detect them under good, dark conditions. Binoculars will allow

us to see down to magnitude 8, and the Observatory telescope can reach visual

magnitude 17 or 22 photographically. The world's biggest telescopes have

detected stars and galaxies as faint as magnitude 30. The sixteen very brightest

stars are assigned magnitudes of 0 or even -1. The brightest star, Sirius, has a

magnitude of -1.44. Jupiter can reach -2.4, and Venus can be more than 6 times

brighter at magnitude -4.7, bright enough to cast shadows. The Full Moon can

reach magnitude -12 and the overhead Sun is magnitude -26.5. Each magnitude step

is 2.51 times brighter or fainter than the next one, i.e. a magnitude 3.0 star

is 2.51 times brighter than a magnitude 4.0. Magnitude 1.0 stars are 100 times

brighter than magnitude 6.0 (5 steps each of 2.51 times,

2.51x2.51x2.51x2.51x2.51 = 2.515 =

The Four Minute Rule

How long does it take the Earth to complete

one rotation? No, it's not 24 hours - that is the time taken for the Sun to

cross the meridian on successive days. This 24 hours is a little longer than one

complete rotation, as the curve in the Earth's orbit means that it needs to turn

a fraction more (~1 degree of angle) in order for the Sun to cross the meridian

again. It is called a 'solar day'. The stars, clusters, nebulae and galaxies are

so distant that most appear to have fixed positions in the night sky on a human

time-scale, and for a star to return to the same point in the sky relative to a

fixed observer takes 23 hours 56 minutes 4.0916 seconds. This is the time taken

for the Earth to complete exactly one rotation, and is called a 'sidereal day'.

As our clocks and lives are organised to run on solar days of 24 hours, and the

stars circulate in 23 hours 56 minutes approximately, there is a four minute

difference between the movement of the Sun and the movement of the stars. This

causes the following phenomena:

1. The Sun slowly moves in the sky relative

to the stars by four minutes of time or one degree of angle per day. Over the

course of a year it moves ~4 minutes X 365 days = 24 hours, and ~1 degree X 365

= 360 degrees or a complete circle. Together, both these facts mean that after

the course of a year the Sun returns to exactly the same position relative to

the stars, ready for the whole process to begin again.

2.

For a given clock time, say 8:00 pm, the stars on consecutive evenings are ~4

minutes or ~1 degree further on than they were the previous night. This means

that the stars, as well as their nightly movement caused by the Earth's

rotation, also drift further west for a given time as the weeks pass. The stars

of autumn, such as Orion, are lost below the western horizon by mid-June, and

new constellations, such as Sagittarius, have appeared in the east. The

stars change with the seasons, and after a year, they are all back where they

started, thanks to the Earth's having completed a revolution of the Sun and

returned to its theoretical starting point.

We can therefore say

that the star patterns we see in the sky at 11:00 pm tonight will be identical

to those we see at 10:32 pm this day next week (4 minutes X 7 = 28 minutes

earlier), and will be identical to those of 9:00 pm this date next month or 7:00

pm the month after. All the above also includes the Moon and planets, but their

movements are made more complicated, for as well as the Four Minute Drift

with the stars, they also drift at different rates against the starry

background, the closest ones drifting the fastest (such as the Moon or Venus),

and the most distant ones (such as Saturn or Neptune) moving the slowest.

Observing astronomical objects depends on

whether the sky is free of clouds. Not only that, but there are other factors

such as wind, presence of high-altitude jet streams, air temperature, humidity

(affecting dew formation on equipment), transparency (clarity of the air),

"seeing" (the amount of air turbulence present), and air pressure. Even the

finest optical telescope has its performance constrained by these factors.

Fortunately, there is an Australian website that predicts the presence and

effects of these phenomena for a period up to five days ahead of the current

date, which enables amateur and professional astronomers to plan their observing

sessions for the week ahead. It is called "SkippySky". The writer has

found its predictions to be quite reliable, and recommends the website as a

practical resource. The website is at

http://skippysky.com.au and the

detailed Australian data are at

http://skippysky.com.au/Australia/ .

Solar System

Sun:

The Sun begins the month in the zodiacal constellation of Virgo, the Virgin. It leaves Virgo and passes into Libra, the Scales on October 31. Note: the Zodiacal constellations used in astrology have significant differences with the familiar astronomical constellations both in size and the timing of the passage through them of the Sun, Moon and planets.

The Moon is tidally locked to the Earth, i.e. it keeps its near hemisphere facing us at all times, while its far hemisphere is never seen from Earth. This tidal locking is caused by the Earth's gravity. The far side remained unknown until the Russian probe Luna 3 went around the Moon and photographed it on October 7, 1959. Now the whole Moon has been photographed in very fine detail by orbiting satellites. The Moon circles the Earth once in a month (originally 'moonth'), the exact period being 27 days 7 hours 43 minutes 11.5 seconds. Its speed is about 1 kilometre per second or 3679 kilometres per hour. The Moon's average distance from the Earth is 384 400 kilometres, but the orbit is not perfectly circular. It is slightly elliptical, with an eccentricity of 5.5%. This means that each month, the Moon's distance from Earth varies between an apogee (furthest distance) of 406 600 kilometres, and a perigee (closest distance) of 356 400 kilometres. These apogee and perigee distances vary slightly from month to month. In the early 17th century, the first lunar observers to use telescopes found that the Moon had a monthly side-to-side 'wobble', which enabled them to observe features which were brought into view by the wobble and then taken out of sight again. The wobble, called 'libration', amounted to 7º 54' in longitude and 6º 50' in latitude. The 'libration zone' on the Moon is the area around the edge of the Moon that comes into and out of view each month, due to libration. This effect means that, instead of only seeing 50% of the Moon from Earth, we can see up to 59%.

The animation loop below shows the appearance of the Moon over one month. The

changing phases are obvious, as is the changing size as the Moon comes closer to

Earth at perigee, and moves away from the Earth at apogee. The wobble due to

libration is the other feature to note, making the Moon appear to sway from side

to side and nod up and down.

.gif)

ANNULAR, OCTOBER 3 (AEST): This total eclipse of the Sun will not be visible from Australia. It will begin in the northern Pacific Ocean and will head south-east towards Cape Horn in South America. The only places where the eclipse path will cross land are in the far south of Chile and Argentina, and the Falkland Islands.

The next total solar eclipse visible from parts of Australia will occur at 12:56 pm on July 22, 2028, the eclipse track running from Wyndham in Western Australia through Alice Springs to Birdsville and then Sydney, before crossing the Tasman Sea to Dunedin in New Zealand's South Island.

Lunar Phases:

New Moon:

November 1 22:48 hrs

diameter = 29.6' Lunation #1260 begins

Last Quarter:

November 23 11:29 hrs

diameter = 30.0'

Lunar Orbital Elements:

October 16

November

Moon at 8 days after

New, as on October 12.

The photograph above shows the Moon when approximately eight days after New, just after First Quarter. A rotatable view of the Moon, with ability to zoom in close to the surface (including the far side), and giving detailed information on each feature, may be downloaded

here. A professional version of this freeware with excellent pictures from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Chang orbiter (giving a resolution of 50 metres on the Moon's surface) and many other useful features is available on a DVD from the same website for 20 Euros (about AU $ 33) plus postage

Lunar Feature for this Month

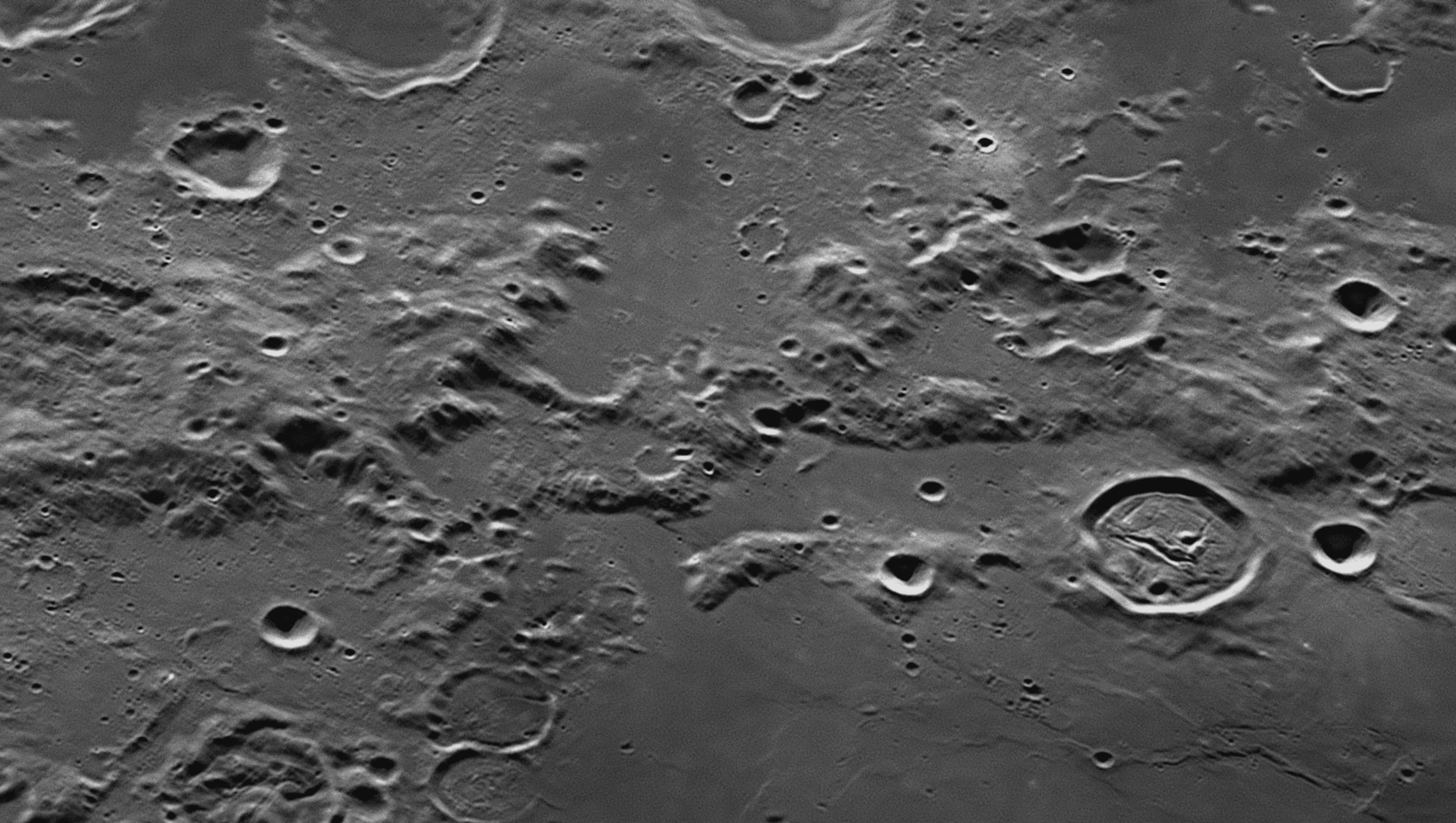

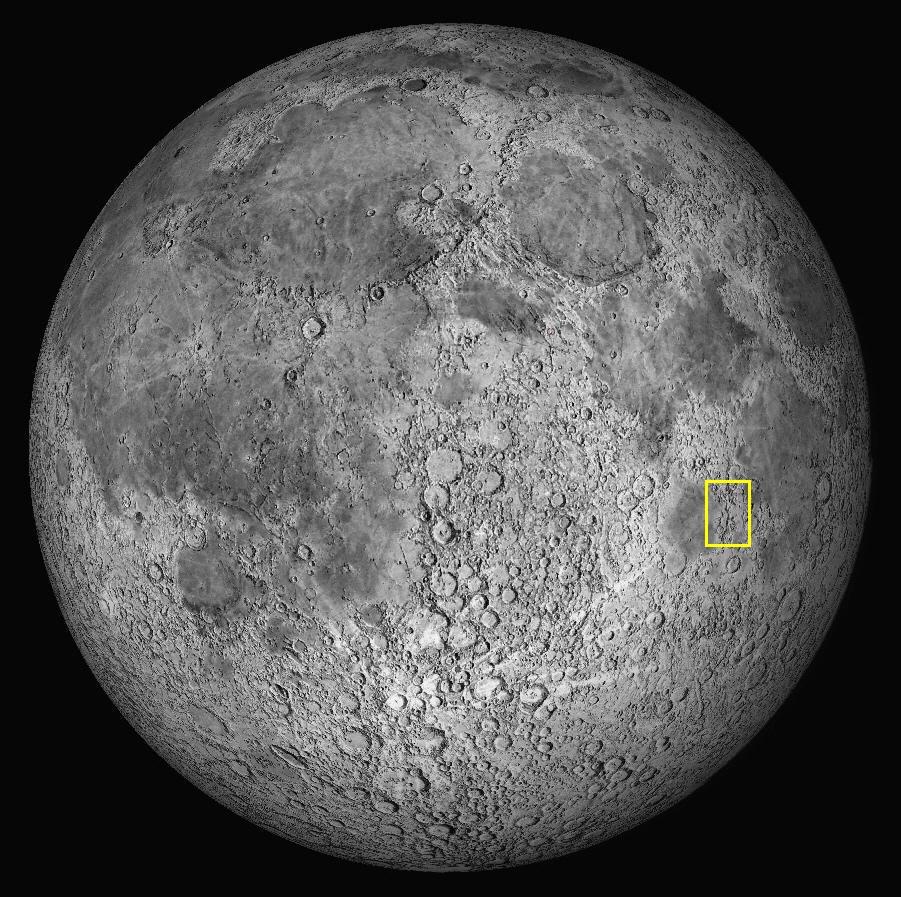

Each month we describe a lunar crater, cluster of craters, valley, mountain range or other object, chosen at random, but one with interesting attributes. A recent photograph from our Alluna RC20 telescope will illustrate the object. As all large lunar objects are named, the origin of the name will be given if it is important. This month we will look at a rugged but disjointed mountain range in the Moon's south-eastern quadrant, the Montes Pyrenaeus (Pyrenees Mountains).

The Montes Pyrenaeus run from north (left margin) to south (right margin) and cover a distance of 250 kilometres. They begin in a pyroclastic area associated with the crater-plain Gutenberg (off image, but see item #25

of the Lunar Feature of the Month Archive ). They occupy an upland area between the Mare Fecunditatis (Sea of Fertility) and the Mare Nectaris (Sea of Nectar). This image was taken at 6:03 pm on 14 August 2021.The Montes Pyrenaeus are composed of mountains that vary in altitude from the highest in the north (3700 metres) to those in the south (up to 2000 metres). A small, parallel range rises abruptly from the Mare Nectaris at the bottom centre of the image, east of which is a level valley running south to a 33 kilometre crater called Bohnenberger which has a severely fractured floor with many rilles and an off-centre mountain. The main range of the Montes Pyrenaeus runs parallel to the valley and extends from the crater-plain Gutenberg (just off the left margin) horizontally across the image to the small craters Bohnenberger G and E. Three crater-plains that are partially shown at the top margin are Goclenius (55 kilometres diameter, at the top-left corner), Magelhaens (41 kilometres diameter, to the right of Goclenius) and Colombo A (42 kilometres diameter, centre of top margin.

A very unusual crater may be seen near the lower-left corner of this image. This is Gaudibert, 33 kilometres in diameter. Its floor has been forced upwards by upwelling magma, and shows numerous fissures and large domes of solidified lava covering the entire interior. Other craters in the area also show fissures crossing their floors, but the spectacular domes in Gaudibert seem unique. There are some ghost craters in this image, created by mare lavas forcing their way into bowl-shaped craters by breaching their walls, and then filling up the floor to the same level as the plain outside, so that only the highest parts of the crater wall remain visible. An example that is easy to recognise may be found near the top right-hand corner, two more are near the centre of the image.

Gutenberg

Christophorus Columbus

October 1: Mercury in superior conjunction at 6:56 hrs (diameter = 4.8" )

October 3: Annular Solar Eclipse at 4:45 am - not visible from Australia

October 3: Limb of Moon 38 arcminutes south of Mercury at 6:59 hrs hrs

October 4: Moon 1º north of the star Spica (Alpha Virginis, mv = 0.98) at 8:32 hrs

October 5: Venus 50 arcminutes south of the star Zuben Elgenubi (Alpha Librae, mv = 2.72) at 4:41 hrs

October 6: Moon 2.1º south of Venus at 3:47 hrs

October 7: Moon 1º north of the star Pi Scorpii (mv = 2.82) at 16:54 hrs

October 8: Moon occults the star Alniyat (Sigma Scorpii, mv = 2.9) between 1:51 and 2:32 hrs

October 8: Limb of Moon 20 arcminutes north of the star Antares (Alpha Scorpii, mv = 0.88) at 4:57 hrs

October 8: Moon 2º north of the star 23 Tau Scorpii (mv = 2.82) at 7:01 hrs

October 9: Jupiter at western stationary point at 16:53 hrs (diameter = 43.3" )

October 10: Moon 2.2º north of the star Alnasl (Gamma Sagittarii, mv = 2.98) at 00:11 hrs

October 10: Moon 1.9º north of the star Kaus Media (Delta Sagittarii, mv = 2.72) at 4:55 hrs

October 10: Mercury 2.4º north of the star Spica (Alpha Virginis, mv = 0.98) at 15:31 hrs

October 10: Moon 1.6º south of the star Nunki (Sigma Sagittarii, mv = 2.02) at 20:31 hrs

October 10: Moon 2.3º north of the star Ascella (Zeta Sagittarii, mv = 2.6) at 23:10 hrs

October 12: Limb of Moon 36 arcminutes south of Pluto at 2:58 hrs

October 12: Pluto at eastern stationary point at 6:41 hrs (diameter = 0.1" )

October 13: Limb of Moon 39 arcminutes south of the star Deneb Algedi (Delta Capricorni, mv = 2.85) at 19:24 hrs

October 14: Mars at western quadrature at 17:53 hrs (diameter = 8.2" )

October 15: Limb of Moon 40 arcminutes north of Saturn at 5:06 hrs

October 16: Moon 2.3º north of Neptune at 1:19 hrs

October 19: Moon 4.8º north of Uranus at 23:10 hrs

October 20: Limb of Moon 32 arcminutes north of the star Alcyone (Eta Tauri, mv = 2.85) at 8:00 hrs

October 20: Venus 45 arcminutes north of the star Dschubba (Delta Scorpii, mv = 1.86) at 15:10 hrs

October 21: Venus 3º south of the star Graffias (Beta1 Scorpii, mv = 2.56) at 3:10 hrs

October 21: Moon 5.7º north of Jupiter at 16:42 hrs

October 21: Moon occults the star Elnath (Beta Tauri, mv = 1.65) between 18:58 and 19:35 hrs

October 24: Mercury at aphelion at 00:43 hrs ( diameter = 5.0" )

October 24: Mercury 1.5º south of the star Zuben Elgenubi (Alpha Librae, mv = 2.72) at 3:28 hrs

October 24: Limb of Moon 38 arcminutes south of the star Pollux (Beta Geminorum, mv = 1.1) at 2:35 hrs

October 24: Moon 4.2º north of Mars at 8:52 hrs

October 24: Venus 2.6º north of the star Alniyat (Sigma Scorpii, mv = 2.9) at 22:45 hrs

October 25: Jupiter 17 arcminutes north of the star 109 Xi Tauri (mv = 4.96) at 11:28 hrs

October 26: Venus 3.1º north of the star Antares (Alpha Scorpii, mv = 0.88) at 14:36 hrs

October 27: Venus 4.5º north of the star 23 Tau Scorpii (mv = 2.82) at 22:36 hrs

October 30: Venus at aphelion at 19:56 hrs ( diameter = 14.1" )

October 31: Limb of Moon 15 arcminutes north of the star Spica (Alpha Virginis, mv = 0.98) at 17:30 hrs

November 3: Moon 1.9º south of Mercury at 18:28 hrs

November 3: Moon 1.6º north of the star Pi Scorpii (mv= 2.82) at 22:48 hrs

November 4: Moon occults the star Alniyat (Sigma Scorpii, mv = 2.9) between 5:36 and 6:22 hrs

November 4: Moon occults the star Antares (Alpha Scorpii, mv = 0.88) between 9:34 and 10:27 hrs

November 4: Moon 1.3º north of the star 23 Tau Scorpii (mv = 2.82) at 15:04 hrs

November 5: Moon 2.6º south of Venus at 7:54 hrs

November 6: Moon 2.5º north of the star Alnasl (Gamma Sagittarii, mv = 2.98) at 3:55 hrs

November 6: Moon 1.6º north of the star Kaus Media (Delta Sagittarii, mv = 2.72) at 9:06 hrs

November 7: Limb of Moon 41 arcminutes south of the star Nunki (Sigma Sagittarii, mv = 2.02) at 1:49 hrs

November 8: Limb of Moon 44 arcminutes south of Pluto at 7:31 hrs

November 9: Mercury 1.5º north of the star Alniyat (Sigma Scorpii, mv = 2.9) at 6:15 hrs

November 10: Moon occults the star Deneb Algedi (Delta Capricorni, mv = 2.85) between 3:35 and 4:14 hrs

November 10: Mercury 2º north of the star Antares (Alpha Scorpii, mv = 0.88) at 20:15 hrs

November 11: Moon has a grazing occultation with Saturn at 10:23 hrs

November 12: Limb of Moon 26 arcminutes north of Neptune at 11:02 hrs

November 13: Venus 1.2º south of the Lagoon Nebula (M8) at 4:15 hrs

November 13: Venus 4.8º north of the star Alnasl (Gamma Sagittarii, mv = 2.98) at 13:15 hrs

November 15: Venus 1.2º north of the star Kaus Media (Delta Sagittarii, mv = 2.72) at 9:06 hrs

November 15: Saturn at eastern stationary point at 23:27 hrs

November 16: Moon 4.3º north of Uranus at 10:12 hrs

November 16: Full Moon occults five stars in the Pleiades cluster (Electra, Celaeno, Merope, Maia and Alcyone) between 15:11 and 16:35 hrs

November 16: Mercury at Greatest Elongation East (22 24') at 19:08 hrs ( diameter = 6.6" )

November 17: Uranus at opposition at 12:16 hrs ( diameter = 3.8" )

November 17: Venus 9 arcminutes south of the star Kaus Borealis (22 Lambda Sagittarii, mv = 2.82) at 18:45 hrs

November 17: Moon 6.3º north of Jupiter ar 23:20 hrs

November 18: Moon occults the star Elnath (Beta Tauri, mv = 1.65) between 7:52 and 8:42 hrs

November 20: Moon 1.8º south of the star Pollux (Beta Geminorum, mv = 1.1) at 13:09 hrs

November 21: Moon 2.4º north of Mars at 10:04 hrs

November 22: Venus 1.1º north of the star Nunki ((Sigma Sagittarii, mv = 2.02) at 22:12 hrs

November 26: Mercury at eastern stationary point at 12:32 hrs ( diameter

= 8.4" )

November 27: Limb of Moon 45 arcminutes north of the star Spica (Alpha Virginis, mv = 0.98) at 22:24 hrs

December 1: Moon 1.8º north of the star Pi Scorpii (mv = 2.82) at 3:03 hrs

Mercury:

Venus:

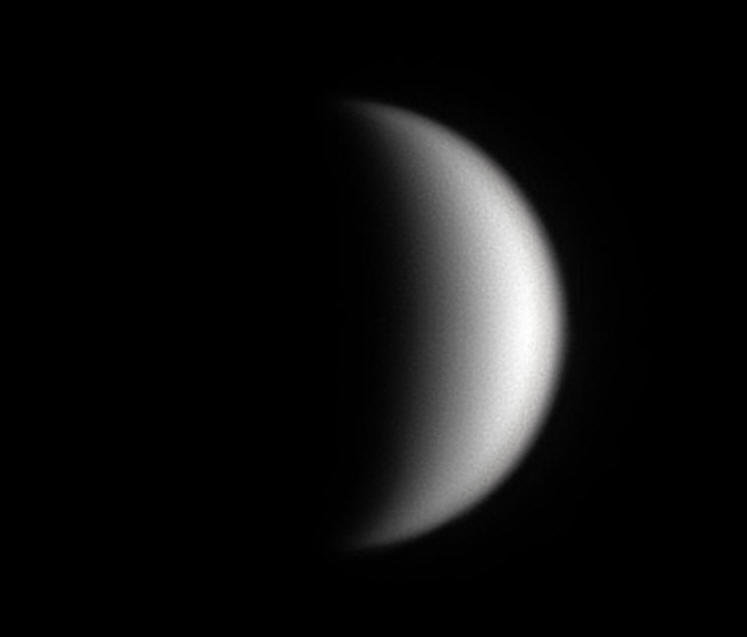

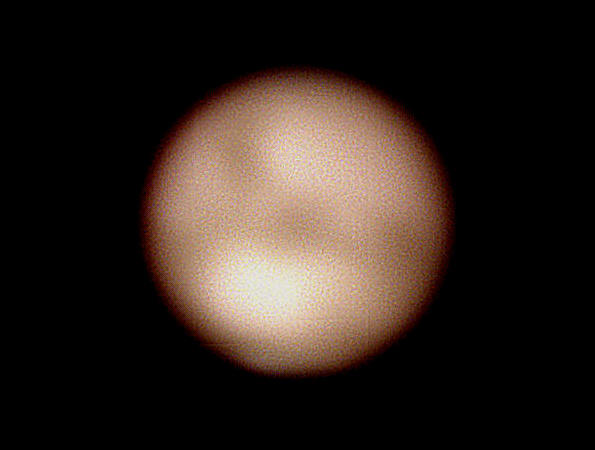

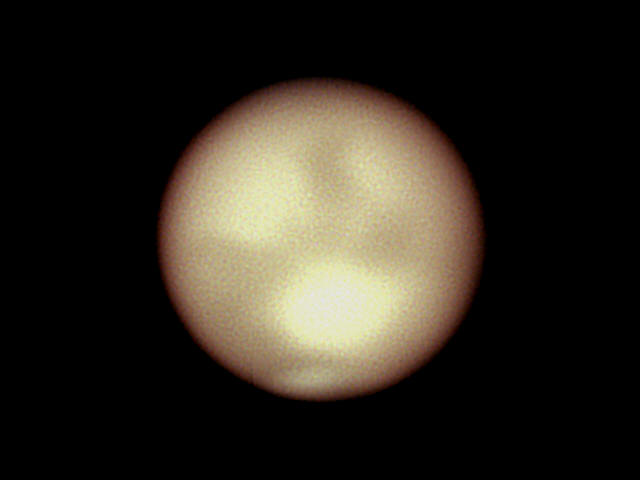

(The coloured fringes to the second, fourth and fifth images below are due to refractive effects in our own atmosphere, and are not intrinsic to Venus itself. The planet was closer to the horizon when these images were taken than it was for the first and third photographs, which were taken when Venus was at its greatest elongation from the Sun.)

October 2023 May-July 2024 January 2025 March 2025 April 2025

C

Because Venus is visible as the 'Evening Star' and as the 'Morning Star', astronomers of ancient times believed that it was two different objects. They called it Hesperus when it appeared in the evening sky and Phosphorus when it was seen before dawn. They also realised that these objects moved with respect to the so-called 'fixed stars' and so were not really stars themselves, but planets (from the Greek word for 'wanderers'). When it was finally realised that the two objects were one and the same, the two names were dropped and the Greeks applied a new name Aphrodite (Goddess of Love) to the planet, to counter Ares (God of War). We use the Roman versions of these names, Venus and Mars, for these two planets.

Venus at 6.55 pm on September 7, 2018. The phase is 36 % and the angular

diameter is 32 arcseconds.

Mars:

At the beginning of October, the red planet is cruising in the centre of the constellation Gemini, and rises in the north-east at about 1 am. It is between the stars Mebsuta

In this image, the south polar cap of Mars is easily seen. Above it is a dark triangular area known as Syrtis Major. Dark Sinus Sabaeus runs off to the left, just south of the equator. Between the south polar cap and the equator is a large desert called Hellas. The desert to upper left is known as Aeria, and that to the north-east of Syrtis Major is called Isidis Regio. Photograph taken in 1971.

Mars photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on June 29 and July 9,

2016, showing two different sides of the planet. The north polar cap is

prominent.

Brilliant Mars at left, shining at magnitude 0.9, passes in front of the dark molecular clouds in Sagittarius on October 15, 2014. At the top margin is the white fourth magnitude star 44 Ophiuchi. Its type is A3 IV:m. Below it and to the left is another star, less bright and orange in colour. This is the sixth magnitude star SAO 185374, and its type is K0 III. To the right (north) of this star is a dark molecular cloud named B74. A line of more dark clouds wends its way down through the image to a small, extremely dense cloud, B68, just right of centre at the bottom margin. In the lower right-hand corner is a long dark cloud shaped like a figure 5. This is the Snake Nebula, B72. Above the Snake is a larger cloud, B77. These dark clouds were discovered by Edward Emerson Barnard at Mount Wilson in 1905. He catalogued 370 of them, hence the initial 'B'. The bright centre of our Galaxy is behind these dark clouds, and is hidden from view. If the clouds were not there, the galactic centre would be so bright that it would turn night into day.

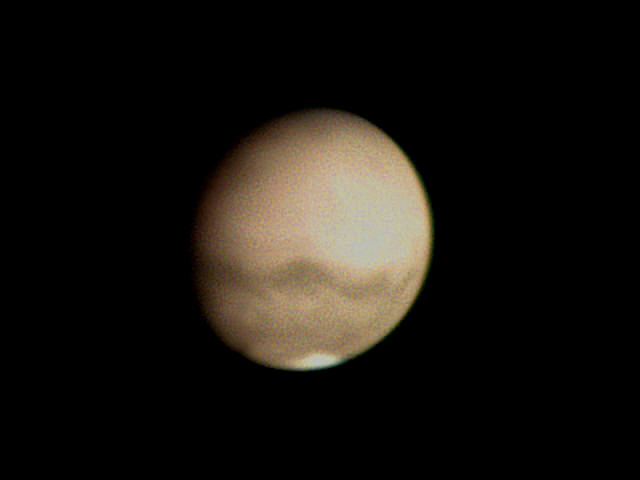

Mars near opposition, July 24, 2018

Mars, called the red planet but usually coloured orange, in mid-2018 took on a yellowish tint and brightened by 0.4 magnitude, making it twice as bright as previous predictions for the July 27 opposition. These phenomena were caused by a great dust storm which completely encircled the planet, obscuring the surface features so that they were only seen faintly through the thick curtain of dust. Although planetary photographers were mostly disappointed, many observers were interested to see that the yellow colour and increased brightness meant that a weather event on a distant planet could actually be detected with the unaided eye - a very unusual thing in itself.

The three pictures above were taken on the evening of July

24, at 9:05, 9:51 and 11:34 pm. Although the fine details that are usually

seen on Mars were hidden by the dust storm, some of the larger features can

be discerned, revealing how much Mars rotates in two and a half hours. Mars'

sidereal rotation period (the time taken for one complete rotation or

'Martian day') is 24 hours 37 minutes 22 seconds - a little longer than an

Earth day. The dust storm began in the Hellas Desert on May 31, and after

two months it still enshrouded the planet. In September it began to clear,

but by then the close approach had passed.

Central meridian: 295º.

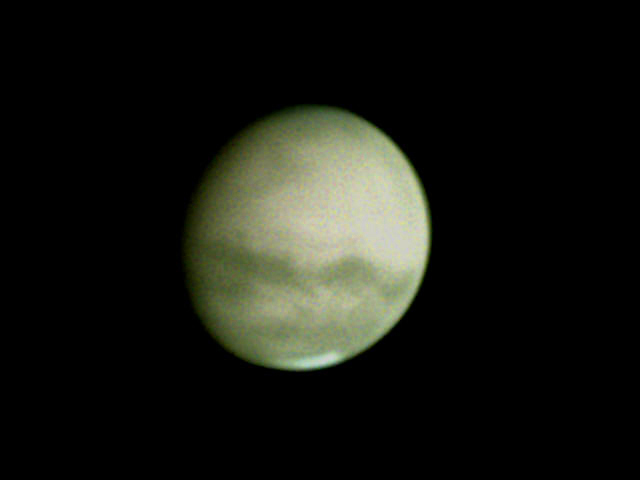

The two pictures immediately above were taken on the evening of September 7, at 6:25 and 8:06 pm. The dust storm was finally abating, and some of the surface features were becoming visible once again. This pair of images also demonstrates the rotation of Mars in 1 hour 41 minutes (equal to 24.6 degrees of longitude), but this time the view is of the opposite side of the planet to the set of three above. As we were now leaving Mars behind, the images are appreciably smaller (the angular diameter of the red planet had fallen to 20 arcseconds). Well past opposition, Mars on September 7 exhibited a phase effect of 92.65 %.

Central meridian: 180º.

Jupiter: Jupiter passed though western quadrature (rising at midnight) on September 12. The waning gibbous Moon will be near Jupiter, close to the north-eastern horizon soon after midnight on October 21. Jupiter will reach opposition with the Sun on December 8.

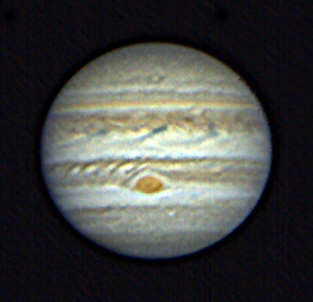

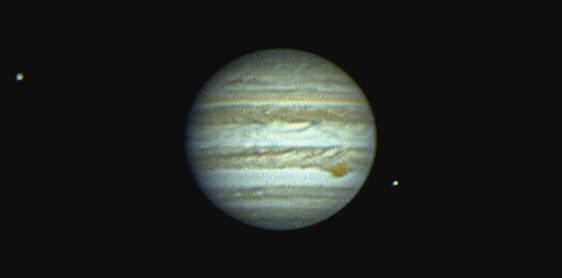

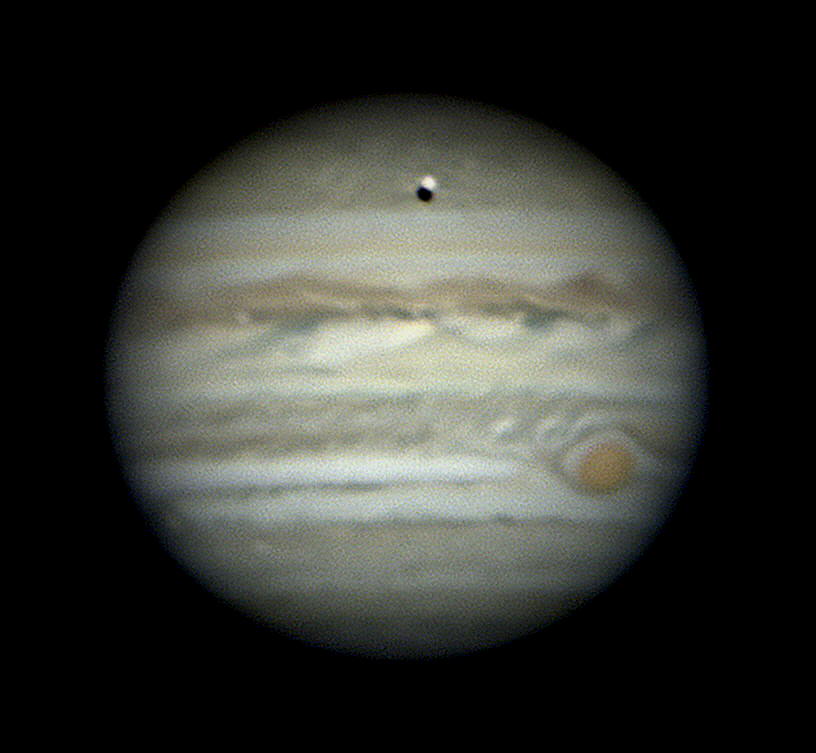

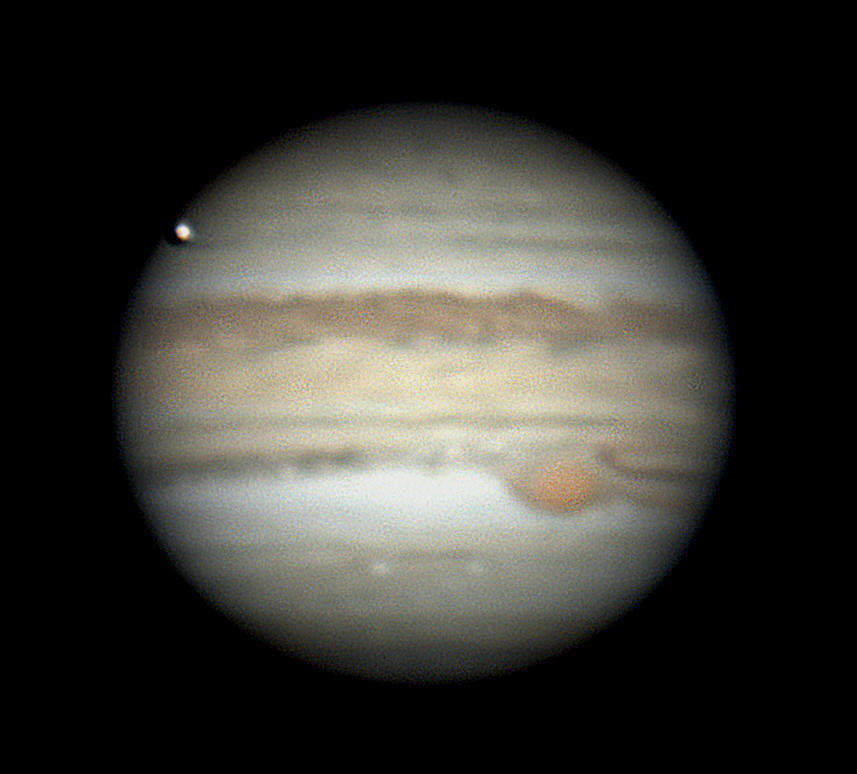

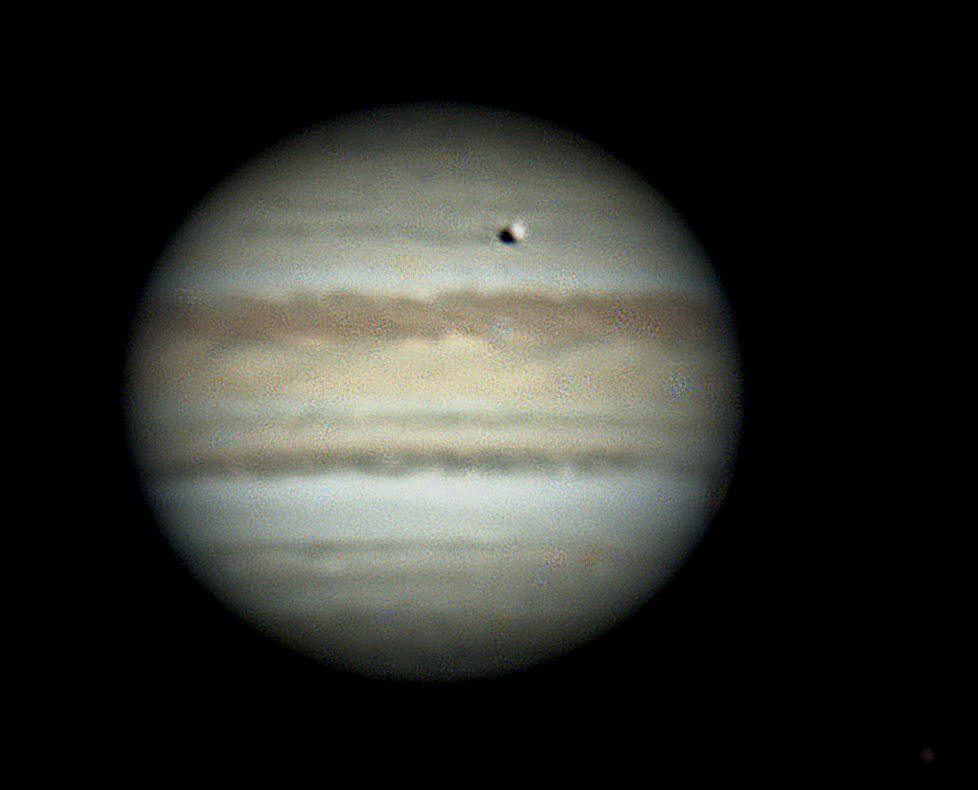

Jupiter as

photographed from Nambour on the evening of April 25, 2017. The images were

taken, from left to right, at 9:10, 9:23, 9:49, 10:06 and 10:37 pm. The rapid

rotation of this giant planet in a little under 10 hours is clearly seen. In the

southern hemisphere, the Great Red Spot (bigger than the Earth) is prominent,

sitting within a 'bay' in the South Tropical Belt. South of it is one of the

numerous White Spots. All of these are features in the cloud tops of Jupiter's

atmosphere.

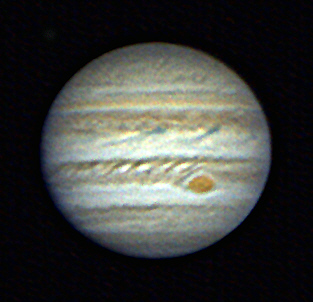

Jupiter at opposition, May 9, 2018

Jupiter as it appeared at 7:29 pm on July 2, 2017. The Great Red Spot was in a

similar position near Jupiter's eastern limb (edge) as in the fourth picture in

the series above. It will be seen that in the past two months the position of

the Spot had drifted when compared with the festoons in the Equatorial Belt, so

must rotate around the planet at a slower rate. In fact, the Belt enclosing the

Great Red Spot rotates around the planet in 9 hours 55 minutes, and the

Equatorial Belt takes five minutes less. This high rate of rotation has made the

planet quite oblate. The prominent 'bay' around the Red Spot in the five earlier

images appeared to be disappearing, and a darker streak along the northern edge

of the South Tropical Belt was moving south. In June this year the Spot began to

shrink in size, losing about 20% of its diameter. Two new white spots have

developed in the South Temperate Belt, west of the Red Spot. The five upper

images were taken near opposition, when the Sun was directly behind the Earth

and illuminating all of Jupiter's disc evenly. The July 2 image was taken just

four days before Eastern Quadrature, when the angle from the Sun to Jupiter and

back to the Earth was at its maximum size. This angle means that we see a tiny

amount of Jupiter's dark side, the shadow being visible around the limb of the

planet on the left-hand side, whereas the right-hand limb is clear and sharp.

Three of Jupiter's Galilean satellites are visible, Ganymede to the left and

Europa to the right. The satellite Io can be detected in a transit of Jupiter,

sitting in front of the North Tropical Belt, just to the left of its centre.

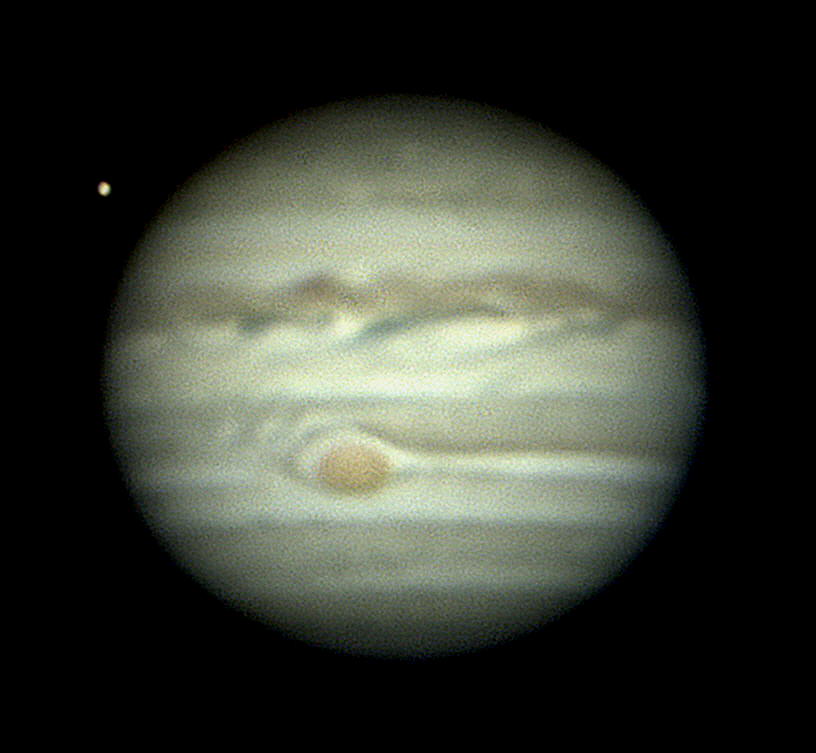

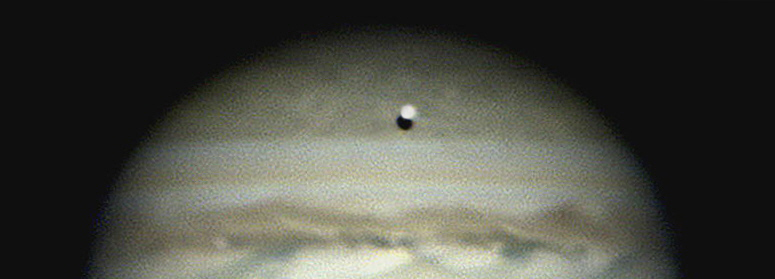

Jupiter reached opposition on May 9, 2018 at 10:21 hrs, and the above photographs were taken that evening, some ten to twelve hours later. The first image above was taken at 9:03 pm, when the Great Red Spot was approaching Jupiter's central meridian and the satellite Europa was preparing to transit Jupiter's disc. Europa's transit began at 9:22 pm, one minute after its shadow had touched Jupiter's cloud tops. The second photograph was taken three minutes later at 9:25 pm, with the Great Red Spot very close to Jupiter's central meridian.

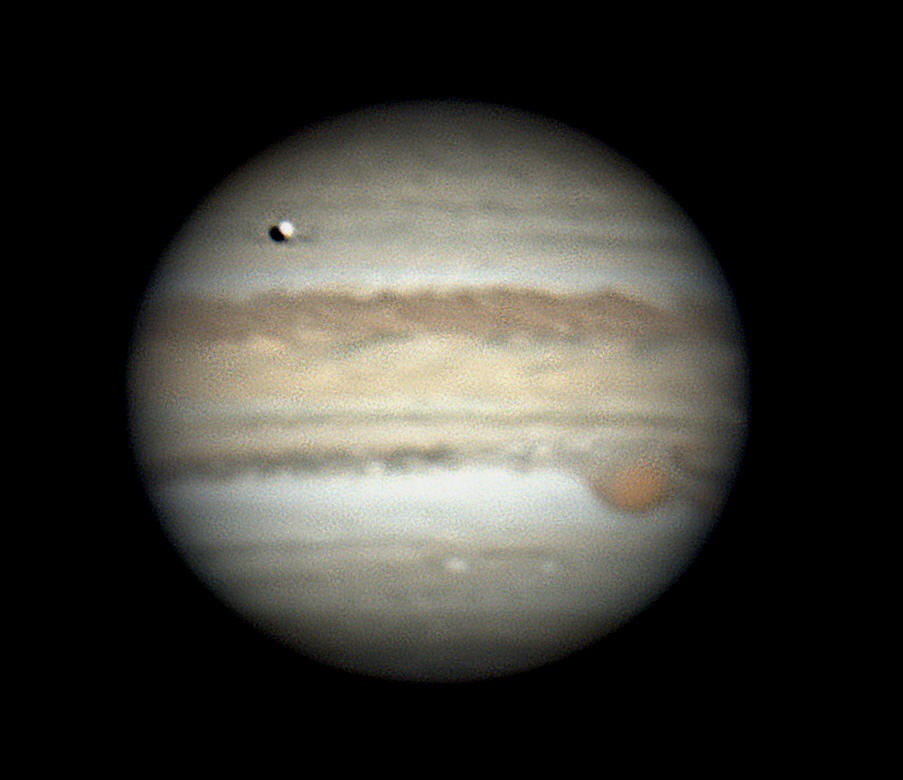

The third photograph was taken at 10:20 pm, when Europa was approaching Jupiter's central meridian. Its dark shadow is behind it, slightly below, on the clouds of the North Temperate Belt. The shadow is partially eclipsed by Europa itself. The fourth photograph at 10:34 pm shows Europa and its shadow well past the central meridian. Europa is the smallest of the Galilean satellites, and has a diameter of 3120 kilometres. It is ice-covered, which accounts for its brightness and whitish colour. Jupiter's elevation above the horizon for the four photographs in order was 50º, 55º, 66º and 71º. As the evening progressed, the air temperature dropped a little and the planet gained altitude. The 'seeing' improved slightly, from Antoniadi IV to Antoniadi III. At the time of the photographs, Europa's angular diameter was 1.57 arcseconds. Part of the final photograph is enlarged below.

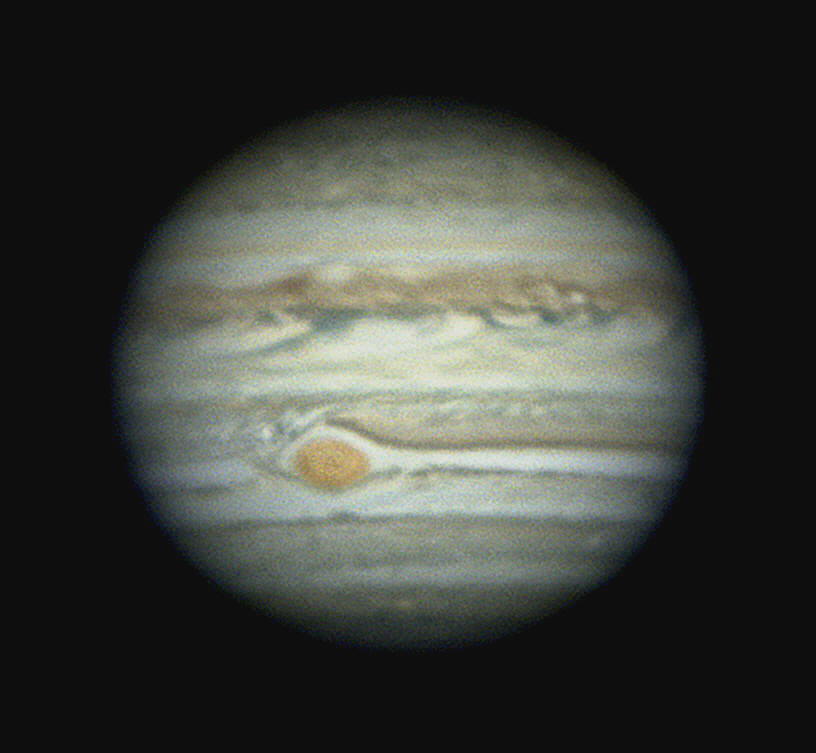

Jupiter at 11:34 pm on May 18, nine days later. Changes in the rotating cloud

patterns are apparent, as some cloud bands rotate faster than others and

interact. Compare with the first photograph in the line of four taken on May 9.

The Great Red Spot is ploughing a furrow through the clouds of the South

Tropical Belt, and is pushing up a turbulent bow wave.

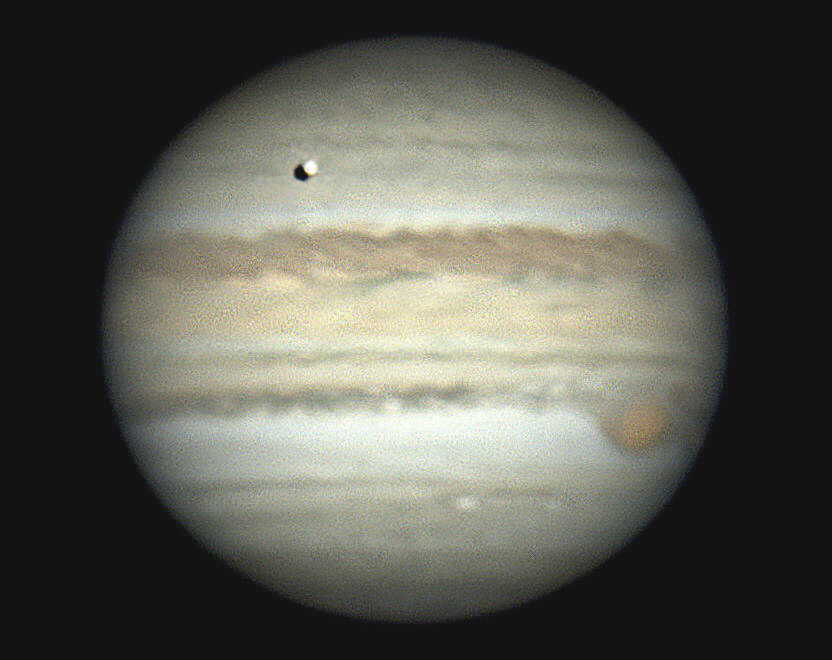

Jupiter at opposition, June 11, 2019

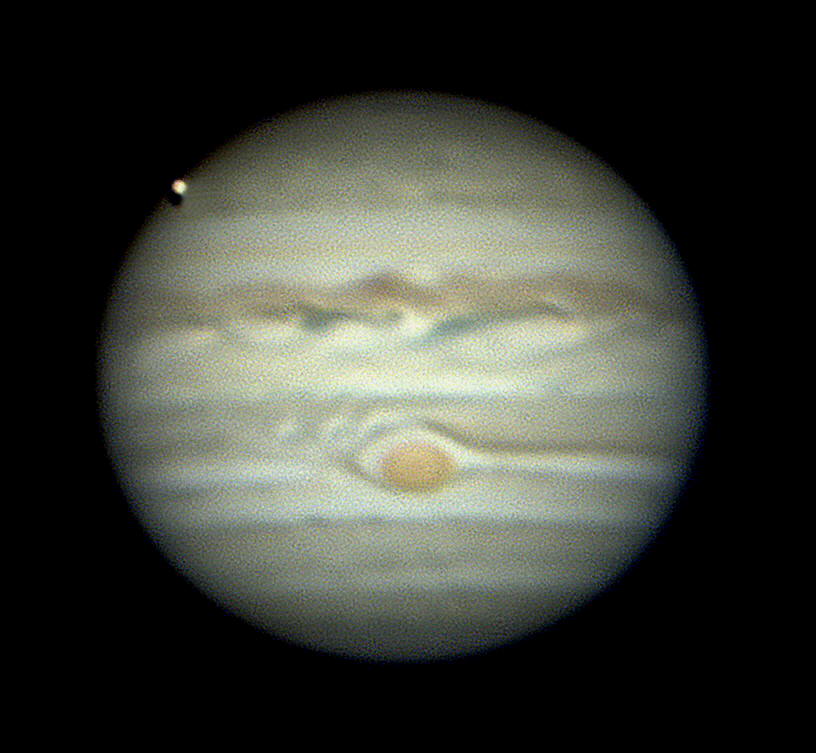

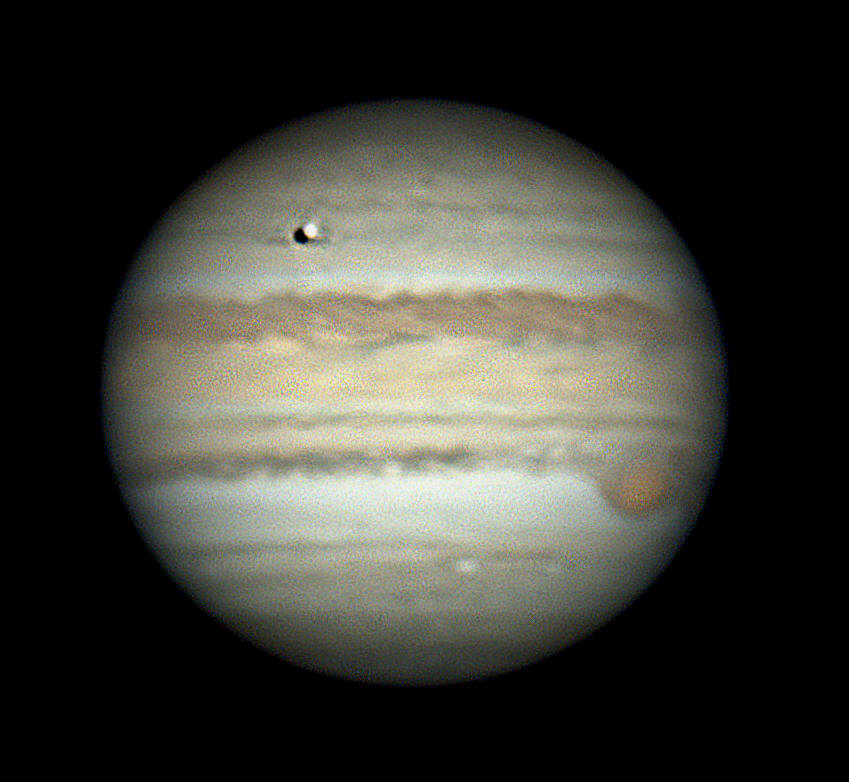

Jupiter reached opposition on June 11, 2019 at 01:20 hrs, and the above

photographs were taken that evening, some twenty to twenty-two hours later. The

first image above was taken at 10:01 pm, when the Great Red Spot was leaving

Jupiter's central meridian and the satellite Europa was preparing to transit

Jupiter's disc.

The third photograph was taken at 10:41 pm, when Europa was about a third of its way across Jupiter. Its dark shadow is trailing it, slightly below, on the clouds of the North Temperate Belt. The shadow is partially eclipsed by Europa itself. The fourth photograph at 10:54 pm shows Europa and its shadow about a quarter of the way across. This image is enlarged below. The fifth photograph shows Europa on Jupiter's central meridian at 11:24 pm, with the Great Red Spot on Jupiter's limb. The sixth photograph taken at 11:45 pm shows Europa about two-thirds of the way through its transit, and the Great Red Spot almost out of sight. In this image, the satellite Callisto may be seen to the lower right of its parent planet. Jupiter's elevation above the horizon for the six photographs in order was 66º, 70º, 75º, 78º, 84º and 86º. As the evening progressed, the 'seeing' proved quite variable.

There have been numerous alterations to Jupiter's belts and spots over the thirteen months since the 2018 opposition. In particular, there have been major disturbances affecting the Great Red Spot, which appears to be slowly changing in size or "unravelling". It was very fortuitous that, during the evenings of the days when the 2018 and 2019 oppositions occurred, there was a transit of one of the satellites as well as the appearance of the Great Red Spot. It was also interesting in that the same satellite, Europa, was involved both times.

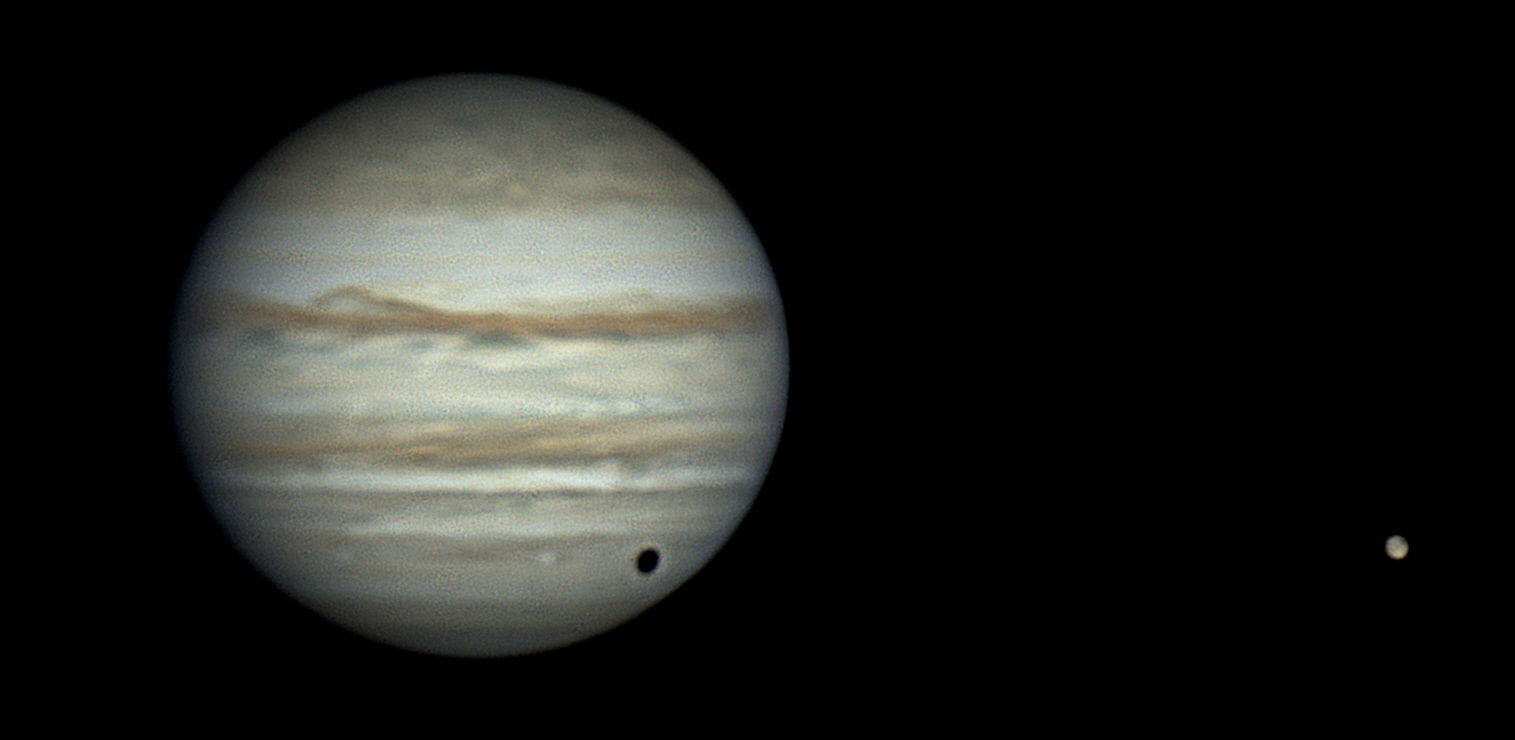

Jupiter's moon Europa has an icy crust with very high reflectivity, which

accounts for its brightness in the images above. On the other hand, the largest

moon Ganymede (seen below) has a surface which is composed of two types of

terrain: very old, highly cratered dark regions, and somewhat younger (but still

ancient) lighter regions marked with an extensive array of grooves and ridges.

Although there is much ice covering the surface, the dark areas contain clays

and organic materials and cover about one third of the moon. Beneath the surface

of Ganymede is believed to be a saltwater ocean with two separate layers.

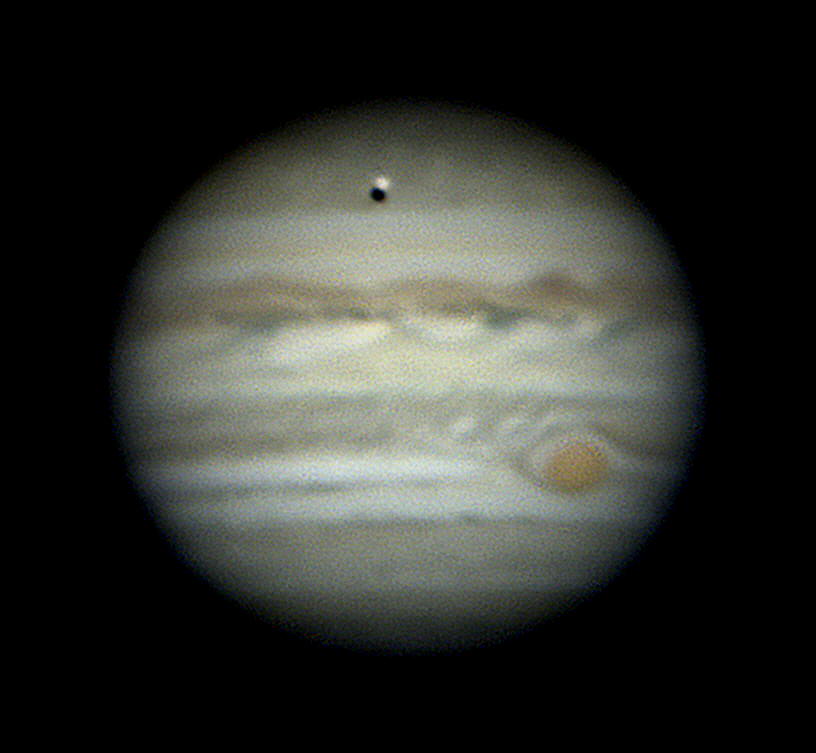

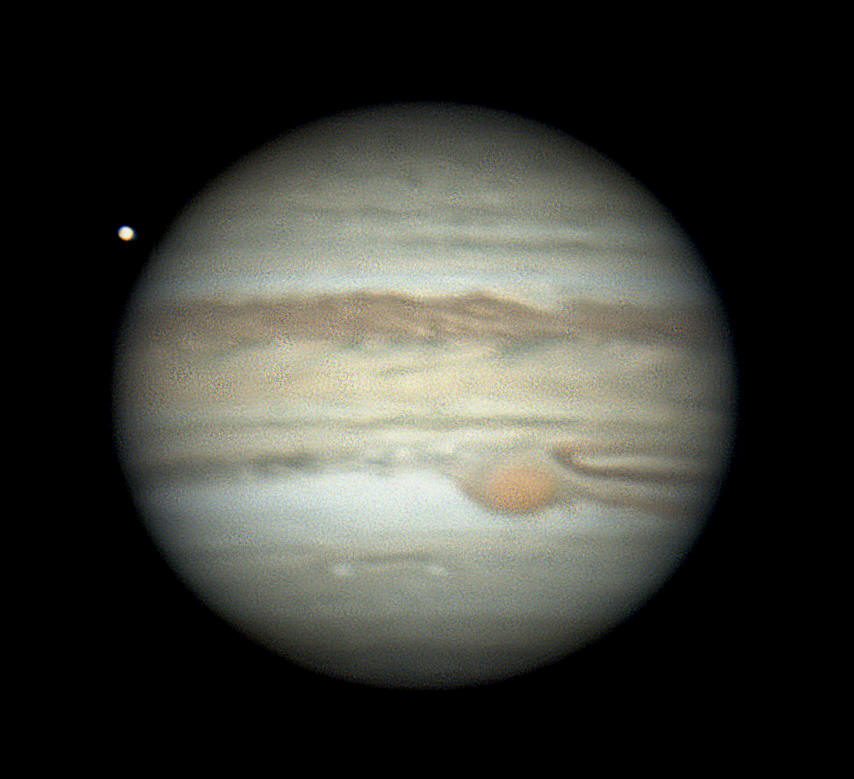

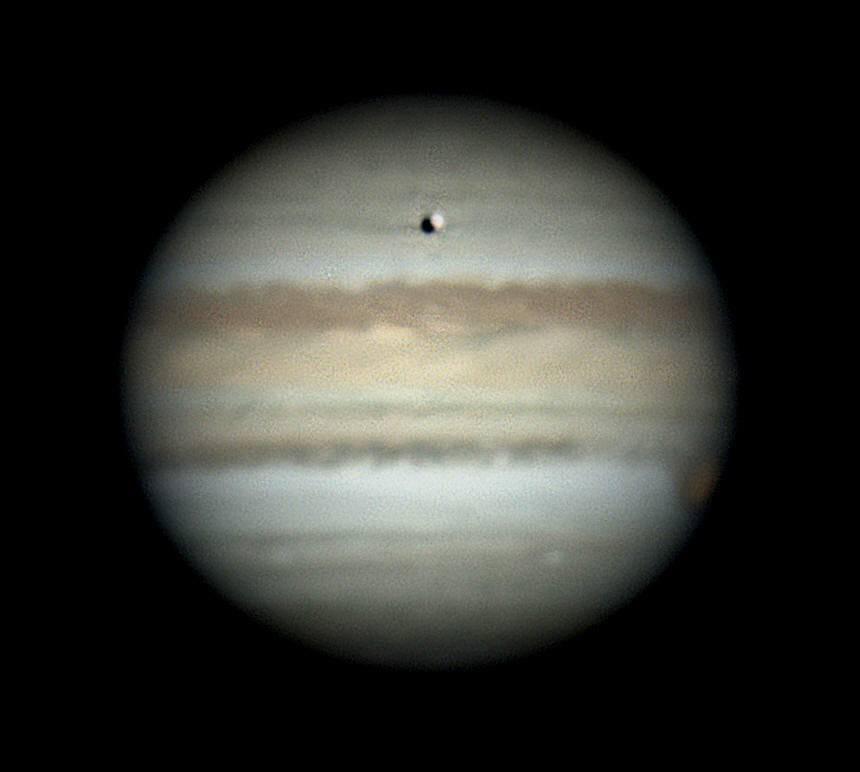

Jupiter is seen here on 17 November

2022 at 8:39 pm. To its far right is its largest satellite, Ganymede. This

"moon" is smaller than the Earth but is bigger than Earth's Moon. Its diameter

is 5268 kilometres, but at Jupiter's distance its angular diameter is only 1.67

arcseconds. Despite its small size, Ganymede is the biggest moon in the Solar

System. Jupiter is approaching eastern quadrature, which means that Ganymede's

shadow is not behind it as in the shadows of Europa in the two sequences taken

at opposition. In the instance above as seen from Earth (which is presently at a

large angle from a line joining the Sun to Ganymede), the circular shadow of

Ganymede is striking the southern hemisphere cloud tops of Jupiter itself. The

shadow is slightly distorted as it strikes the spherical globe of Jupiter. If

there were any inhabitants of Jupiter flying across the cloud bands above, and

passing through the black shadow, they would experience an eclipse of the

distant Sun by the moon Ganymede.

Above is a 7X enlargement of Ganymede, showing markings on its rugged, icy

surface. The dark area in its northern hemisphere is called Galileo Regio.

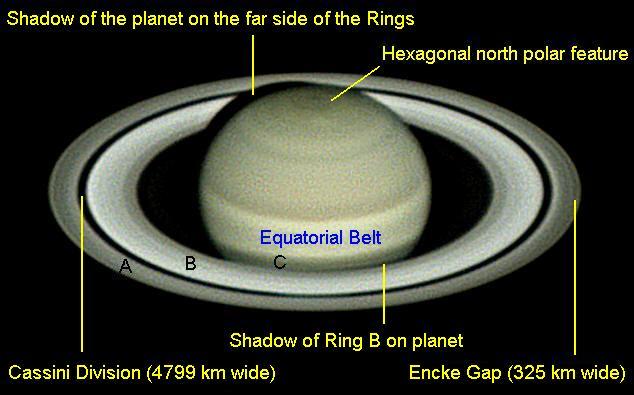

Saturn:

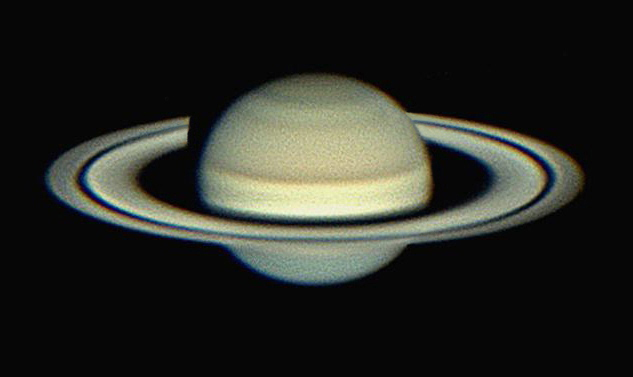

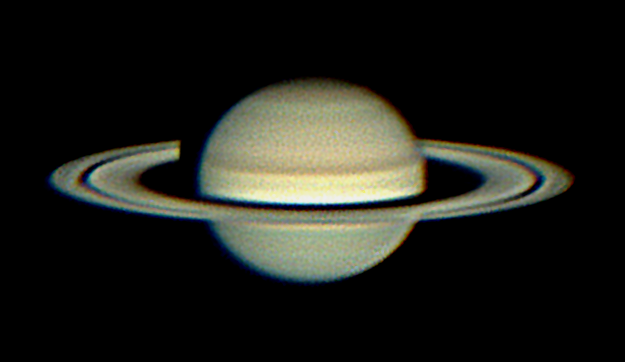

The ringed planet is located in the constellation of Aquarius, and will remain there until it crosses into Pisces on April 19, 2025. Saturn reached opposition with the Sun on September 8. In mid-October it may be found about 54 degrees (three handspans) above the east-north-eastern horizon at 7 pm. Saturn, its rings and its moons will experience a grazing occultation with the almost Full Moon on the morning of November 11, at around 10:21-10:24 am. This event will not be visible from South-east Queensland, as the Moon will not rise until 1:12 pm. The rings of Saturn are nearly edge-on this year. They will be completely edge-on and invisible on March 24 next year.

Left: Saturn showing the Rings when edge-on. Right: Over-exposed Saturn surrounded by its satellites Rhea, Enceladus, Dione, Tethys and Titan - February 23/24, 2009.

The photograph above was taken at 7:41 pm on December 07, 2023, 14 days after

eastern quadrature. The shadow of the planet once more falls across the far side

of the rings, but in the intervening 13 months the angle of the rings as seen

from Earth has lessened considerably. The light-coloured equatorial zone on

Saturn shows through the gap known as the Cassini Division.

The change in aspect of Saturn's rings is caused by the plane of the ring system

being aligned with Saturn's equator, which is itself tilted at an angle of 26.7

degrees to Saturn's orbit. As the Earth's orbit around the Sun is in much the

same plane as Saturn's, and the rings are always tilted in the same direction in

space, as we both orbit the Sun, observers on Earth see the configuration of the

rings change from wide open (top large picture) to half-open (bottom large

picture) and finally to edge on (small picture above). This cycle is due to

Saturn taking 29.457 years to complete an orbit of the Sun, so the complete

cycle from

"edge-on (2009) → view of Northern hemisphere, rings half-open (2013) →

wide-open (2017) → half-open (2022) → edge-on (March 2025) → view of Southern

hemisphere, rings half-open (2029) → wide-open (2032) → half-open (2036) →

edge-on (2039)"

takes 29.457 years. The angle of the rings will continue to reduce until they

are edge-on again in 2025. They will appear so thin that it will seem that

Saturn has no rings at all.

Uranus:

Neptune:

T

Neptune, photographed from Nambour on October 31, 2008

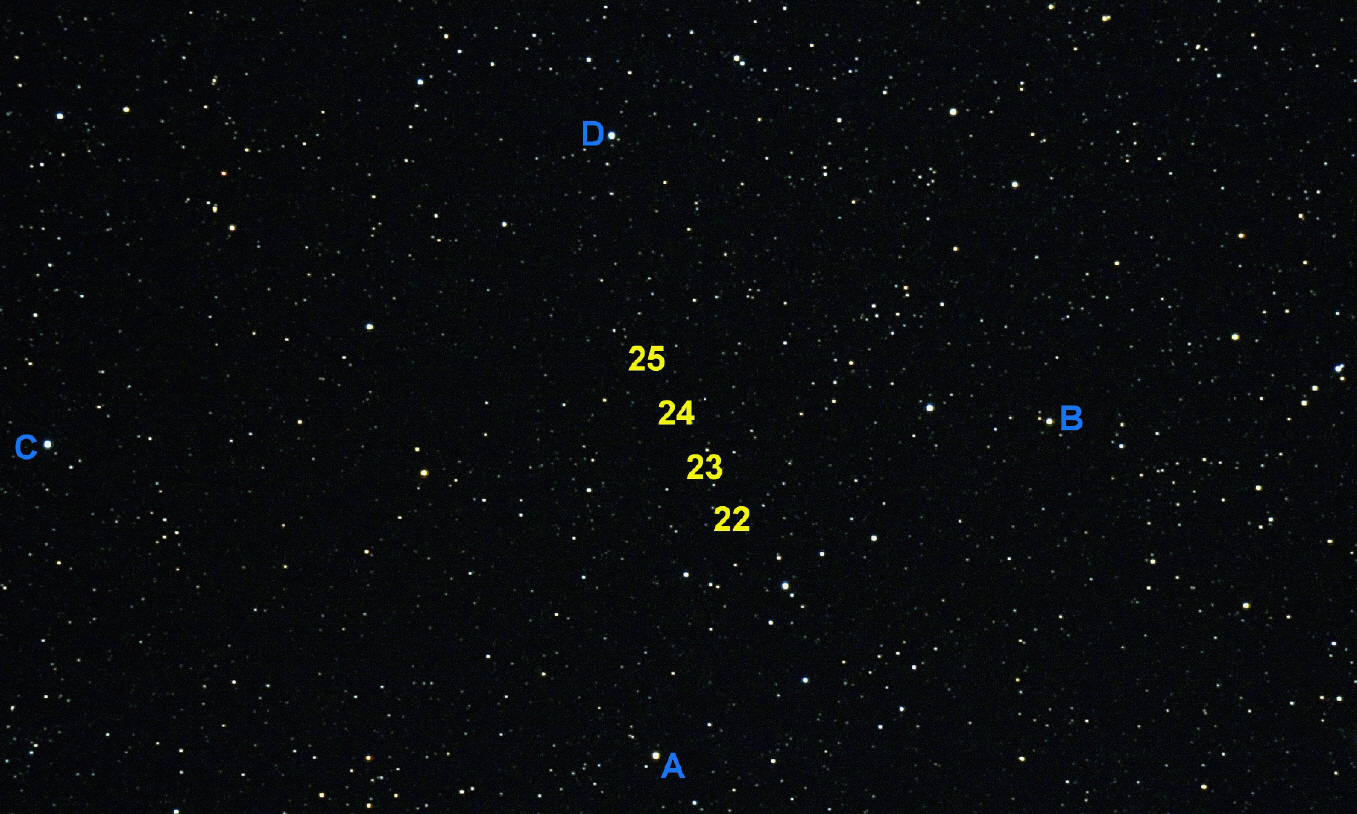

Pluto: The

erstwhile ninth and most distant planet passed through

The movement of the dwarf planet Pluto in two days, between 13 and 15 September,

2008. Pluto is the one object that has moved.

Width of field:

200 arcseconds

This is a stack of four images, showing the movement of Pluto over the period October 22 to 25, 2014. Pluto's image for each date appears as a star-like point at the upper right corner of the numerals. The four are equidistant points on an almost-straight line. Four eleventh magnitude field stars are identified. A is GSC 6292:20, mv = 11.6. B is GSC 6288:1587, mv = 11.9. C is GSC 6292:171, mv = 11.2.

D is GSC 6292:36, mv = 11.5. (GSC = Guide Star Catalogue). The position of Pluto on October 24 (centre of image) was at Right Ascension = 18 hours 48 minutes 13 seconds, Declination = -20º 39' 11". The planet moved 2' 51" with respect to the stellar background during the three days between the first and last images, or 57 arcseconds per day, or 1 arcsecond every 25¼ minutes.

Here are the positions of the planets above the horizon in mid-October, at

1:30 am: Saturn is at an altitude of 19º (about a handspan) above the western horizon. 14.3º (about three-quarters of a handspan) east of Saturn is Neptune, which will require the use of a small telescope to find. Uranus

has passed through culmination (crossing the

meridian or north-south line), and is about 43º above the northern horizon. Jupiter has an altitude of two handspans above the north-north-western horizon, and Mars is

three-quarters of a handspan above the north-eastern horizon (Jupiter is much brighter than Mars).

The movements of planets including their alignments and close-up images can be watched using the freeware

On October 1 there will be a fine grouping of Mars, Jupiter and Uranus in the north-eastern sky

after midnight. It will be quite spectacular, as the star clusters the Pleiades (Seven Sisters) and the Hyades will be nearby, as well as the bright stars Alderbaran, Betelgeuse and Capella. Not far away will be the stars Sirius, Rigel and Procyon,

and the Twins Pollux and Castor.. Mars is moving eastwards during October, from

central Gemini into Cancer on October 30. Jupiter will move away from the clusters in Taurus, also heading towards Gemini. The waning crescent

Moon will pass through this grouping from October 20 to 24.

Meteor

Showers:

Use this

ZHR

Although most meteors are found in swarms associated with debris from comets, there are numerous 'loners', meteors travelling on solitary

paths through space. When these enter our atmosphere, unannounced and at any time, they are known as 'sporadics'. On an average clear and dark evening, an

observer can expect to see about ten meteors per hour. They burn up to ash in their passage through our atmosphere. The ash slowly settles to the ground as

meteoric dust. The Earth gains about 80 tonnes of such dust every day, so a percentage of the soil we walk on is actually interplanetary in origin. If a

meteor survives its passage through the air and reaches the ground, it is called a 'meteorite'. In the past, large meteorites (possibly comet nuclei or small asteroids) collided with the Earth and produced huge craters which still exist

today. These craters are called 'astroblemes'. Two famous ones in Australia are Wolfe Creek Crater and Gosse's Bluff. The Moon and Mercury are covered with such

astroblemes, and craters are also found on Venus, Mars, planetary satellites, minor planets, asteroids and even comets.

Comets:

This periodic comet returns every 71 years, and is in our western twilight sky at present. Look due west, close to the horizon as soon as the sky darkens. On 16 July, the comet was near the magnitude 2.2 star Suhail (Lambda Velorum).

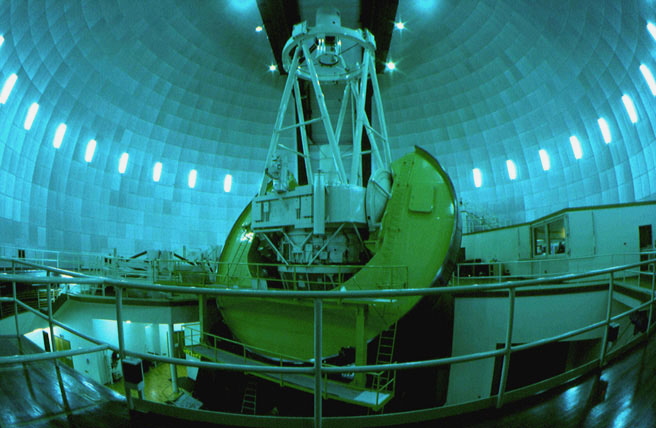

This comet was discovered on 2 March 2022 at the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF)

at the Hale Observatory on Mount Palomar. It was found on CCD images taken by

the famous 48-inch Schmidt Telescope. It

Both of these comets appeared recently in orbits that caused them to dive

towards the Sun's surface before swinging around the Sun and heading back

towards the far reaches of the Solar System. Such comets are called 'Sun

grazers', and their close approach to the Sun takes them through its immensely

powerful gravitational field and the hot outer atmosphere called the 'corona'.

They brighten considerably during their approach, but most do not survive and

disintegrate as the ice which holds them together melts. While expectations were

high that these two would emerge from their encounter and put on a display as

bright comets with long tails when they left the Sun, as they came close to the

Sun they both broke up into small fragments of rock and ice and ceased to exist.

Comet 46P/Wirtanen In December 2018, Comet 46P/Wirtanen swept

past Earth, making one of the ten closest approaches of a comet to our planet

since 1960. It was faintly visible to the naked eye for two weeks. Although

Wirtanen's nucleus is only 1.2 kilometres across, its green atmosphere

became larger than the Full Moon, and was an easy target for binoculars and

small telescopes. It reached its closest to the Sun (perihelion) on December 12,

and then headed in our direction. It passed the Earth at a distance of 11.5

million kilometres (30 times as far away as the Moon) on December 16, 2018.

Green Comet ZTF (C/2022 E3)

Comet SWAN (C/2020 F8) and Comet ATLAS (2019 Y4)

Comet Lulin

This comet, (C/2007 N3), discovered

Comet Lulin at 11:25 pm on February 28, 2009, in Leo. The brightest star is Nu Leonis, magnitude 5.26.

The

LINEARNearly all of these programs are based in the northern hemisphere, leaving gaps in the coverage of the southern sky. These gaps are the areas of sky where amateur astronomers look for comets from their backyard observatories.

To find out more about current comets, including finder charts showing exact positions and magnitudes, click

here. To see pictures of these comets, click here.

The 3.9 metre Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) at the Australian Astronomical Observatory near Coonabarabran, NSW.

Deep Space

Sky Charts and Maps available on-line:

There are some useful

representations of the sky available here. The sky charts linked below show the

sky as it appears to the unaided eye. Stars rise four minutes earlier each

night, so at the end of a week the stars have gained about half an hour. After a

month they have gained two hours. In other words, the stars that were positioned

in the sky at 8 pm at the beginning of a month will have the same positions at 6

pm by the end of that month. After 12 months the stars have gained 12 x 2 hours

= 24 hours = 1 day, so after a year the stars have returned to their original

positions for the chosen time. This accounts for the slow changing of the starry

sky as the seasons progress.

The following interactive sky charts are courtesy of Sky and Telescope magazine. They can simulate a view of the sky from any location on Earth at any time of day or night between the years 1600 and 2400. You can also print an all-sky map. A Java-enabled web browser is required. You will need to specify the location, date and time before the charts are generated. The accuracy of the charts will depend on your computer’s clock being set to the correct time and date.

To produce a real-time sky chart (i.e. a chart showing the sky at the instant the chart is generated), enter the name of your nearest city and the country. You will also need to enter the approximate latitude and longitude of your observing site. For the Sunshine Coast, these are:

latitude: 26.6o South longitude: 153o East

Then enter your time, by scrolling down through the list of cities to "Brisbane: UT + 10 hours". Enter this one if you are located near this city, as Nambour is. The code means that Brisbane is ten hours ahead of Universal Time (UT), which is related to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), the time observed at longitude 0o, which passes through London, England. Click here to generate these charts.

_____________________________________

Similar real-time charts can also be generated from another source, by following

this second link:

The first, circular chart will show the full hemisphere of sky overhead. The zenith is at the centre of the circle, and the cardinal points are shown around the circumference, which marks the horizon. The chart also shows the positions of the Moon and planets at that time. As the chart is rather cluttered, click on a part of it to show that section of the sky in greater detail. Also, click on Update to make the screen concurrent with the ever-moving sky.

The stars and constellations around the horizon to an elevation of about 40o can be examined by clicking on

The view can be panned around the horizon, 45 degrees at a time. Scrolling down the screen will reveal tables showing setup and customising options, and an Ephemeris showing the positions of the Sun, Moon and planets, and whether they are visible at the time or not. These charts and data are from YourSky, produced by John Walker.

The charts above and the descriptions below assume that the observer has a good observing site with a low, flat horizon that is not too much obscured by buildings or trees. Detection of fainter sky objects is greatly assisted if the observer can avoid bright lights, or, ideally, travel to a dark sky site. On the Sunshine Coast, one merely has to travel a few kilometres west of the coastal strip to enjoy magnificent sky views. On the Blackall Range, simply avoid streetlights. Allow your eyes about 15 minutes to become dark-adapted, a little longer if you have been watching television. Small binoculars can provide some amazing views, and with a small telescope, the sky’s the limit.

This month,

These descriptions of the night sky are for 9 pm on October 1 and 7 pm on October

31. Broadly speaking, the following description starts low in the north-west and

follows the horizon to the right, heading round to the east, then south, then

west, then overhead and back to the north-west.

Whereas most binaries are a pair of similar stars, there are many in which the two stars are very different, such as brilliant

Sirius the Dog Star with its tiny white dwarf companion known as 'The Pup'. Albireo's two components have a marked colour contrast, the brighter star being a golden yellow, and the

fainter companion being a vivid electric blue. It is a wonderful object to view with a small telescope. At the top of the Northern Cross is the brightest star in the constellation. It appears close to the north-north-western horizon tonight. This star is

the first magnitude star Deneb, or Alpha Cygni. Deneb is a white giant star, and is the nineteenth brightest in the sky. Its name is Arabic for 'tail'. It will be

due north at about 7.00 pm at mid-month. High in the sky and approaching culmination is the Great Square of Pegasus. It will be standing directly above the northern horizon at 9.30 pm at

mid-month. It is very large, each side being around 15 degrees long. It is about as large as a fist held at arm's length, and is a similar distance above the horizon. The

Great Square is remarkable for having few naked-eye stars within it. The names of the four stars marking the corners of the Square (starting at the top-left one and moving in a clockwise direction around the Square) are

Markab, Algenib, Alpheratz and Scheat. Although these four stars are known as the Great Square of Pegasus, only three are actually in the

constellation of Pegasus, the Winged Horse. In point of fact, Alpheratz is the brightest star of the constellation

Andromeda, the Chained Maiden. Andromeda trails down from Alpheratz below the north-eastern horizon. To its right is the zodiacal constellation of

Aries, now risen in the

north-east. The brightest star in Aries is a second magnitude orange star called

Hamal. Above it is the white star Sheratan, slightly fainter.

In the east, a mv 2.2 star is about halfway up the sky. This is Beta Ceti, the brightest ordinary star in the constellation Cetus,

the Whale. Its common name is Diphda, and it has a yellowish-orange colour. By rights, the star Menkar being also known as Alpha Ceti should be

brighter, but Menkar is actually more than half a magnitude fainter than Diphda. Menkar may be seen rising above the east-north-eastern horizon. Cetus is a large constellation, running around the eastern horizon tonight, and to the unaided eye it appears unremarkable. But it does contain a most

interesting star, which even ancient peoples noticed. The astronomer Hevelius named it Mira, the Wonderful (see below). Between Cetus and Pegasus is the zodiacal constellation of

Pisces, the Fishes. Pisces is found just above Aries, and contains a faint ring of stars, known as the 'Circlet'.

The planet Neptune is currently in the western end of Pisces. Above Diphda is Fomalhaut, a bright, white first magnitude star in the faint constellation Piscis Austrinus, the Southern Fish. Above

Fomalhaut and to the right is a large, flattened triangle of stars, Grus, the Crane. Fomalhaut and Grus are both almost directly overhead at this time. Very high in the south-east is Achernar, which is the ninth brightest star. It is the main star in the constellation Eridanus the River,

which winds its way from Achernar towards the eastern horizon below Cetus. It then continues below the horizon all the way to

Orion, which this month will not rise above the eastern horizon until a little after 10.00 pm.

Achernar's visual magnitude ( mv ) is 0.45, and it is a hot blue-white star of B3 spectral type. The width of the field is 24 arcminutes and the faintest

stars are mv 15. Between Achernar and the south-eastern horizon can be seen the brilliant supergiant

Canopus rising in the south-east. Canopus is the second-brightest star in the night sky, being outshone only by Sirius, which is smaller but much closer. To the left of Achernar, the faint constellation of Phoenix may be seen. Its brightest star is Ankaa, a mv 2.39 star which is

halfway between Diphda and Achernar, but slightly above. A little to the east of due south, the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) is gaining altitude. The Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) is about a

handspan above it, and to the right of Achernar. Both of these Clouds appear as faint smudges of light, but in reality they are dwarf galaxies containing millions of

stars. From our latitude both Magellanic Clouds are circumpolar. This means that they are closer to the South Celestial Pole than that Pole's

altitude above the horizon, so they never dip below the horizon. They never rise nor set, but are always in our sky. Of course, they are not visible in daylight, but they

are there, all the same. The Southern Cross is almost out of sight below the southern horizon, and Alpha and Beta Centauri are setting nearby. Near the

west-south-western horizon, we see the bright S-shaped constellation of Scorpius, the Scorpion, with the red-supergiant star Antares marking the Scorpion's

heart. From October 8 on, the planet Venus will be passing through Scorpius, and on October 16 and 17 will be within 1.5º of Antares.

The Stars and Constellations for this month:

The adjoining constellation of Sagittarius, the Archer is about 45º above the south-western horizon, just

above Scorpius. The star clouds in the centre of our Milky Way galaxy lie behind the stars of Sagittarius.

Antares, a red supergiant

The star which we call Antares is a binary system. It is dominated by the great red supergiant Antares A which, if it swapped places with our Sun, would enclose all the planets out to Jupiter inside itself. Antares A is accompanied by the much smaller Antares B at a distance of between 224 and 529 AU - the estimates vary. (One AU or Astronomical Unit is the distance of the Earth from the Sun, or about 150 million kilometres or 8.3 light minutes.) Antares B is a bluish-white companion, which, although it is dwarfed by its huge primary, is actually a main sequence star of type B2.5V, itself substantially larger and hotter than our Sun. Antares B is difficult to observe as it is less than three arcseconds from Antares A and is swamped in the glare of its brilliant neighbour. It can be seen in the picture above, at position angle 277 degrees (almost due west or to the left) of Antares A. Seeing at the time was about IV on the Antoniadi Scale, or in other words below fair. Image acquired at Starfield Observatory in Nambour on July 1, 2017.

The centre of our galaxy is teeming with stars, and would be bright enough to turn night into day, were it not for intervening dust and molecular clouds. This dark cloud was discovered by Edward Emerson Barnard in 1905 and is known as B72, 'The Snake'. A satellite passed through the field of view at right.

East of Sagittarius and a little to the west of the zenith is Capricornus, the Sea-Goat.

Between Capricornus and Pisces is a rather faint constellation, Aquarius, the Water Bearer. Aquarius is almost directly overhead at this time, and this year

contains the planet Saturn, which lies about two-thirds of a handspan south-east of the asterism known as the 'Water Jar'.

The constellations Sagittarius (top) and Scorpius (bottom), with the elegant curve of Corona Australis to the left of Sagittarius. They are high in the west at 8.00 pm this month.

High in the north-west, between Capricornus and Albireo, is the constellation of Aquila, the Eagle. The centre of this constellation is marked by a short line of three stars, of which the centre star is the brightest. These stars, from left to right, are Tarazed, Altair and Alshain, and they indicate the Eagle's body. A handspan east of the bright, first magnitude Altair is a faint but easily recognised diamond-shaped group of stars, Delphinus the Dolphin.

Vega is the brightest star at centre left, with the stars of Lyra to its right. Deneb is the brightest star near the bottom edge. Cygnus, or the 'Northern Cross', stretches up vertically from Deneb to Albireo, above centre. We see the Northern Cross upside-down. The three bright stars of Aquila form a line at upper right, with Altair, the brightest, being the middle one. The small diamond-shaped constellation of Delphinus, the Dolphin, is above centre-right.

The zodiacal constellations visible tonight, starting from the west-south-western horizon and heading north-east, are Scorpius, Sagittarius, Capricornus, Aquarius, Pisces and Aries.

More photographs of the amazing sights visible in our sky this month are found in our Picture Gallery.

If you would like to become familiar with the constellations, we suggest that you access one of the world's best collections of constellation pictures by clicking

here. To see some of the best astrophotographs taken with the giant Anglo-Australian telescope, click here.

Mira, the Wonderful

The amazing thing about the star

Mira or Omicron Ceti is that it

varies dramatically in brightness, rising to magnitude 2 (brighter than any other star in Cetus), and then dropping to magnitude 10 (requiring a telescope

to detect it), over a period of 332 days.

This drop of eight magnitudes means that its brightness diminishes over a period of five and a half months to one six-hundredth of what it had been, and then over the next five and a half months it regains its original brightness.

The seventeenth century Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius named it Mira, meaning 'The Wonderful' or 'The Miraculous One'.

We now know that many stars vary in brightness, even our Sun doing so to a small degree, with a period of 11 years. One type of star varies, not because it is actually becoming less bright in itself, but because another, fainter star moves around it in an orbit roughly in line with the Earth, and obscures it on each pass. This type of star is called an eclipsing variable and they are very common.

The star Mira though, varies its light output because of processes in its interior. It is what is known as a pulsating variable. Stars of the Mira type are giant pulsating red stars that vary between 2.5 and 11 magnitudes in brightness. They have long, regular periods of pulsation which lie in the range from 80 to 1000 days.

In 2022, Mira reached a maximum brightness of magnitude 3.4 on July 16 and then faded slowly, dropping well below naked-eye visibility (magnitude 9) by February of 2023. It then brightened rapidly, and reached that year's maximum on June 13. Now it has faded again, and reached its minimum brightness early in 2024. A small telescope was needed in order to find it. By Easter it brightened again and reached maximum brightness on May 10, 2024. It was then a morning sky object, rising on that day at 4:48 am. Each of these cycles lasts 332 days. Mira is now fading and will reach a minimum around this coming Christmas. It will then brighten again and will reach its next maximum on April 6, 2025. On that date it will rise at 7:03 am and set at 7:17 pm.

Mira near minimum, 26 September 2008 Mira near maximum, 22 December 2008

Astronomers using a NASA space telescope, the Galaxy Evolution Explorer, have spotted an amazingly long comet-like tail behind Mira as the star streaks through space.

Galaxy Evolution Explorer - "GALEX" for short - scanned the well-known star during its ongoing survey of the entire sky in ultraviolet light. Astronomers then noticed what looked like a comet with a gargantuan tail. In fact, material blowing off Mira is forming a wake 13 light-years long, or about 20,000 times the average distance of Pluto from the sun. Nothing like this has ever been seen before around a star. More, including pictures

Double and multiple stars

Estimate

Binary stars may have similar components (Alpha Centauri A and B are both stars like our Sun), or they may be completely dissimilar, as with Albireo (Beta Cygni, where a bright golden giant star is paired with a smaller bluish main sequence star).

The binary stars Rigil Kent (Alpha Centauri) at left, and Beta Cygni (Albireo), at right.

The binary star Rigel (Beta Orionis, left) is a large white supergiant which is 500 times brighter than its small companion, Rigel B, Yet Rigel B is itself composed or a very close pair of Sun-type stars that orbit each other in less than 10 days. In the centre of the Great Nebula in Orion (M42) is a multiple star known as the Trapezium (right). This star system has four bright white stars, two of which are binary stars with fainter red companions, giving a total of six. The hazy background is caused by the cloud of fluorescing hydrogen comprising the nebula.

Acrux, the brightest star in the Southern Cross, is also known as Alpha Crucis. It is a close binary, circled by a third dwarf companion.

Alpha Centauri (also known as Rigil Kentaurus, Rigil Kent or Toliman) is a binary easily seen with a small telescope. The components are both solar-type main sequence stars, one of type G and the other, slightly cooler and fainter, of type K. Through a telescope this star system looks like a pair of distant but bright car headlights. Alpha Centauri A and B take 80 years to complete an orbit, but a tiny third component, the 11th magnitude red dwarf Proxima Centauri, takes about 1 million years to orbit the other two. It is about one tenth of a light year from the bright pair and a little closer to us, hence its name. This makes it our nearest interstellar neighbour, with a distance of 4.3 light years. Red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star, but, being so small and faint, none is visible to the unaided eye. Because they use up so little of their energy, they are also the longest-lived of stars. The bigger a star is, the shorter its life.

Close-up of the star field around Proxima Centauri

Knowing the orbital period of the two brightest stars A and B, we can apply Kepler’s Third Law to find the distance they are apart. This tells us that Alpha Centauri A and B are about 2700 million kilometres apart or about 2.5 light hours. This makes them a little less than the distance apart of the Sun and Uranus (the orbital period of Uranus is 84 years, that of Alpha Centauri A and B is 80 years.)

Albireo (Beta Cygni) is sometimes described poetically as a large topaz with a small blue sapphire. It is one of the sky’s most beautiful objects. The stars are of classes G and B, making a wonderful colour contrast. It lies at a distance of 410 light years, 95 times further away than Alpha Centauri.

Binary stars may be widely spaced, as the two examples just mentioned, or so close that a telescope is struggling to separate them (Acrux, Antares, Sirius). Even closer double stars cannot be split by the telescope, but the spectroscope can disclose their true nature by revealing clues in the absorption lines in their spectra. These examples are called spectroscopic binaries. In a binary system, closer stars will have shorter periods for the stars to complete an orbit. Eta Cassiopeiae takes 480 years for the stars to circle each other. The binary with the shortest period is AM Canum Venaticorum, which takes only 17½ minutes.

Sometimes one star in a binary system will pass in front of the other one, partially blocking offs light. The total light output of the pair will be seen to vary, as regular as clockwork. These are called eclipsing binaries, and are a type of variable star, although the stars themselves usually do not vary.

The Milky Way

A glowing band of light crossing the sky is especially noticeable during the winter months,

and to a lesser extent in the spring, when it appears more to the west. This glow is the light of millions of faint stars combined with that coming from

glowing gas clouds called nebulae. It is concentrated along the plane of our galaxy, and this month it is seen crossing the western half of the sky, starting from the

south-south-west and passing through Crux to Norma, Ara, Scorpius, Sagittarius, Scutum and Aquila to Cygnus in the north-north-west.

The plane of our galaxy from Scutum (at left) through Sagittarius and Scorpius (centre) to Centaurus and Crux (right). The Eta Carinae nebula is at the right margin, below centre. The Coalsack is clearly visible, and the dark dust lanes can be seen. Taken with an ultra-wide-angle lens.

It is rewarding to scan along this band with a pair of binoculars, looking for star clusters and emission nebulae. Dust lanes along the plane of the Milky Way appear to split it in two in some parts of the sky. One of these lanes can be easily seen, starting near Alpha Centauri and heading towards Antares.

The centre of our galaxy. The constellations partly visible here are Sagittarius (left), Ophiuchus (above centre) and Scorpius (at right). The planet Jupiter is the bright object below centre left. This is a normal unaided-eye view.

The Season of the Scorpion

The rest of the stars run around the scorpion's tail, ending with two blue-white B type stars, Shaula (the brighter of the two) and Lesath,

at the tip of the scorpion's sting. These two stars are at the eastern end of the constellation, and are near the top of the picture below. West of Lesath in the body of

the scorpion is an optical double star, which can be seen as two with the unaided eye.

The spectacular constellation of Scorpius is about a handspan above the western horizon at about 8.00 pm in mid-October. Three bright stars in a gentle

curve mark his head, and another three mark his body. Of this second group of three, the centre one is a bright, red supergiant, Antares. It marks the

red heart of the scorpion. This star is so large that, if it swapped places with our Sun, it would engulf the Earth and extend to the orbit of Mars. It is 604

light years away and shines at magnitude 1.06. Antares, an M type star, has a faint companion which can be seen in a good amateur telescope.

Scorpius, with its head at lower right, and the tail (with sting) at upper left.

Probably the two constellations most easily recognisable (apart from Crux, the Southern Cross) are Orion the Hunter and Scorpius the Scorpion. Both are large constellations containing numerous bright stars, and are very obvious 'pictures in the sky'. Both also contain a very bright red supergiant star, Betelgeuse in Orion and Antares in Scorpius.

A very distant star that is easily seen with the unaided eye is Zeta Scorpii, in the tail of the Scorpion. Actually, there are two stars there, Zeta 1 and Zeta 2. Zeta 2 is an orange K-type giant star which is only 150 light years away. Zeta 1, though, is a blue-white B1 hypergiant, and at a distance of 2600 light years is over 17 times further away than Zeta 2. The light from Zeta 1 left it around 600 BC, when the Greek philosophers Socrates and Plato were alive. It can be found by following the line of the tail of Scorpius, and is the fourth star from Antares, heading south. It lies at the point where the tail takes a sharp turn east.

Zeta 1 Scorpii is the upper star in the bright group of three at centre right. Zeta 2 is below it.

The

centre of the Lagoon Nebula

Why are some constellations bright, while others are faint ?

The Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy some 100000 – 120000 light-years in diameter which contains

100 – 400 billion stars. It may contain at least as many planets as well. Our galaxy is shaped like a flattened disc with a central bulge. The Solar System is located

within the disc, about 27000 light-years from the Galactic Centre,

on the inner edge of one of the spiral-shaped concentrations of gas and dust called the Orion Arm. When

we look along the plane of the galaxy, either in towards the centre or out towards the edge, we are looking along the disc

through the teeming hordes of stars, clusters, dust clouds and nebulae. In the sky, the galactic plane gives the appearance

which we call the Milky Way, a brighter band of light crossing the sky. This part of the sky is very interesting to observe

with binoculars or telescope. The brightest and most spectacular constellations, such as Crux, Canis Major, Orion and Scorpius

are located close to the Milky Way.

If we look at ninety degrees to the plane, either straight up and out of the galaxy or straight down, we are looking through comparatively few stars and gas clouds and so can see out into deep space. These are the directions of the north and south galactic poles, and because we have a clear view in these directions to distant galaxies, these parts of the sky are called the intergalactic windows. The northern window is between the constellations Virgo and Coma Berenices, roughly between the stars Denebola and Arcturus. It is out of sight this month.

The southern window is in the constellation Sculptor, not far from the star Fomalhaut. This window is in the south-east in the early evening, but later in the night it will rise high enough for distant galaxies to be observed. Some of the fainter and apparently insignificant constellations are found around these windows, and their lack of bright stars, clusters and gas clouds presents us with the opportunity to look across the millions of light years of space to thousands of distant galaxies.

Finding the South Celestial Pole

The South Celestial Pole is that point in the southern sky around which the stars rotate in a clockwise

direction. The Earth's axis is aimed exactly at this point. For an equatorially-mounted telescope, the polar axis of the

mounting also needs to be aligned exactly to this point in the sky for accurate tracking to take place.

To find this point, first locate the Southern Cross. Project a line from the top of the Cross down through its base and continue straight on towards the south for another four Cross lengths. This will locate the approximate spot. There is no bright star to mark the Pole, whereas in the northern hemisphere they have Polaris (the Pole Star) to mark fairly closely the North Celestial Pole.

Another way to locate the South Celestial Pole is to draw an imaginary straight line joining Beta Centauri in the south-west to Achernar in the south-east. Both stars will be at about the same elevation above the horizon at 7.00 pm at the beginning of October. Find the midpoint of this line to locate the pole.

Interesting photographs of this area can be taken by using a camera on time exposure. Set the camera on a tripod pointing due south, and open the shutter for thirty minutes or more. The stars will move during the exposure, being recorded on the film as short arcs of a circle. The arcs will be different colours, like the stars are. All the arcs will have a common centre of curvature, which is the south celestial pole.

A wide-angle view of trails around the South Celestial Pole, with Scorpius and Sagittarius at left, Crux and Centaurus at top, and Carina and False Cross at right

Star trails between the South Celestial Pole and the southern horizon. All stars that do not pass below the horizon are circumpolar.

Star Clusters

The two clusters in Taurus, the Pleiades and the Hyades,

are known as Open Clusters or Galactic Clusters. The name 'open cluster' refers to the fact that the stars in the cluster are grouped together, but not as

tightly as in globular clusters (see below). The stars appear to be loosely arranged, and this is partly due to the fact that the cluster is relatively close to us, i.e.

within our galaxy, hence the alternate name, 'galactic cluster'. These clusters are generally formed from the condensation of gas in a nebula into stars, and some

are relatively young.

The photograph below shows a typical open cluster,

M7*. It lies in the constellation Scorpius, just below the scorpion's sting, in the direction of our galaxy's centre. The cluster itself is the group of white stars in the centre of the field. Its distance is about 380 parsecs or 1240 light years. M7 is visible tonight.

Galactic Cluster M7 in Scorpius

Outside the plane of our galaxy, there is a halo of Globular Clusters. These are very old, dense clusters, containing perhaps several hundred thousand stars. These stars are closer to each other than is usual, and because of its great distance from us, a globular cluster gives the impression of a solid mass of faint stars. Many other galaxies also have a halo of globular clusters circling around them.

The largest and brightest globular cluster in the sky is

The globular cluster Omega Centauri

The central core of Omega Centauri

There is another remarkable globular, second only to Omega Centauri. Close to the SMC (see below), binoculars can detect a fuzzy star. A

telescope will reveal this faint glow as a magnificent globular cluster, lying at a distance of 5.8 kiloparsecs. Its light has taken almost 19 000 years to reach us. This is NGC 104, commonly known as 47 Tucanae. Some regard this cluster as being more spectacular than Omega Centauri, as it is more compact, and the faint stars

twinkling in its core are very beautiful. This month, 47 Tucanae will be observable all night.

The globular cluster 47 Tucanae.

The globular cluster NGC 6752 in the constellation Pavo.

Observers aiming their telescopes towards the SMC generally also look at the nearby 47 Tucanae, but there is another globular cluster nearby which is also worth a visit.

This is NGC 362, which is less than half as bright as the other globular, but this is because it is more than twice as far away. Its distance is 12.6 kiloparsecs or 41 000

light years, so it is about one-fifth of the way from our galaxy to the SMC. Both NGC 104 and NGC 362 are always above the horizon for all parts of Australia south of the

Tropic of Capricorn

* M42: This number means that the Great Nebula in Orion is No. 42 in a list of 103 astronomical objects compiled and published in 1784 by Charles Messier. Charles was interested in the discovery of new comets, and his aim was to provide a list for observers of fuzzy nebulae and clusters which could easily be reported as comets by mistake. Messier's search for comets is now just a footnote to history, but his list of 103 objects is well known to all astronomers today, and has even been extended to 110 objects.

** NGC 5139: This number means that Omega Centauri is No. 5139 in the New General Catalogue of Non-stellar Astronomical Objects. This catalogue was first published in 1888 by J. L. E. Dreyer under the auspices of the Royal Astronomical Society, as his New General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars. It contained only objects that could be seen through a telescope. Soon after it appeared, the new technique of astrophotography became available, revealing thousands more faint objects in space, and also dark, obscuring nebulae and dust clouds. This meant that the NGC had to be supplemented with the addition of two Index Catalogues (IC). Many non-stellar objects in the sky have therefore NGC numbers or IC numbers. For example, the famous Horsehead Nebula in Orion is catalogued as IC 434. The NGC was revised in 1973, and lists 7840 objects.

The recent explosion of discovery in astronomy has meant that more and more catalogues are being produced, but they tend to specialise in particular types of objects, rather than being all-encompassing, as the NGC / IC try to be. Some examples are the Planetary Nebulae Catalogue (PK) which lists 1455 nebulae, the Washington Catalogue of Double Stars (WDS) which lists 12 000 binaries, the General Catalogue of Variable Stars (GCVS) which lists 28 000 variables, and the Principal Galaxy Catalogue (PGC) which lists 73 000 galaxies. The largest modern catalogue is the Hubble Guide Star Catalogue (GSC) which was assembled to support the Hubble Space Telescope's need for guide stars when photographing sky objects. The GSC contains nearly 19 million stars brighter than magnitude 15.

Two close galaxies

The Large Magellanic Cloud - the

bright knot of gas to left of centre is the famous Tarantula Nebula.

Low in the south-south-east, two faint smudges of light may be seen. These are the two Clouds of Magellan, known to astronomers as the

LMC (Large

Magellanic Cloud) and the SMC (Small Magellanic Cloud). The LMC is

directly below the SMC, and is noticeably larger.

They lie at distances of 190 000 light years for the LMC, and 200 000 light years for the SMC. They are about 60 000 light

years apart. These dwarf galaxies circle our own much larger galaxy, the Milky Way,

and are linked to it by the Magellanic Stream. The LMC is slightly closer, but this does

not account for its larger appearance. It really is larger than the SMC, and has developed as an under-sized barred spiral galaxy.

Astronomers have recently reported the largest star yet found, claimed to have 300 times the mass of the Sun, located in a cluster of stars embedded in the Tarantula Nebula (above). Such a huge star would be close to the Eddington Limit, and would have a short lifespan measured in only a couple of million years.

These two Clouds are the closest galaxies to our own, but lie too far south to be seen by the large telescopes in Hawaii, California and Arizona. They are 15 times closer than the famous Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies, and so can be observed in much clearer detail. Our great observatories in Australia, both radio and optical, have for many years been engaged in important research involving these, our nearest inter-galactic neighbours.

Astronomy

Click

here to access a new spectacular picture every day - this link will also provide you with access to a wonderful library of astronomical photographs from telescopes, spacecraft and manned lunar missions.

Virtual Moon freeware>

Study the Moon in close-up, spin it around to see the far side, find the names and physical attributes of craters, seas, ranges and other features, by clicking

Calsky software

Stellarium freeware

New version. Check out where the stars and constellations are, as well as most other sky objects, by clicking

Observatory Home Page and Index