Updated: 5 January 2024

Planets and Comets

Transit of Mercury, 9 November 2006

Sunrise on November 9 occurred at 4.54 am. Soon after, starting at 5.19 am, Mercury was visible through the telescope as a black dot moving across the Sun’s disc. This 'transit of Mercury' lasted until 10.12 am. These transits are quite rare, and the next one will occur on 9 May, 2016. Unfortunately, the next five transits of Mercury will not be visible from Australia, and we will have to wait for 46 years to see the next one from Nambour. The November 9 event occurred on a cloudy morning with some rain, but despite the weather, the following images were captured at Starfield Observatory:

Phases of Venus

April 2017 June 2017 December 2017

Mars near the 2016 opposition

Mars

photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on June 29 and July 9, 2016, showing two

different

sides of the planet. The north polar cap is prominent.

Brilliant

Mars at left, shining at magnitude 0.9, passes in front of the dark molecular clouds in

Sagittarius

on October 15, 2014. At the top margin is the white fourth magnitude

star 44 Ophiuchi. Its type is A3 IV:m.

Below it and to the left is another star,

less bright and orange in colour. This is the sixth magnitude star

SAO 185374,

and its type is K0 III. To the right (north) of this star is a dark molecular

cloud named B74.

A line of more dark clouds wends its way down through the image

to a small, extremely dense cloud, B68,

just right of centre at the bottom

margin. In the lower right-hand corner is a long dark cloud shaped like a figure

5.

This is the Snake Nebula, B72. Above the Snake is a larger cloud, B77.

These

dark clouds were discovered by Edward Emerson Barnard at Mount Wilson in 1905.

He catalogued

370 of them, hence the initial 'B'. The bright centre of our

Galaxy is behind these dark clouds, and is hidden

from view. If the clouds were

not there, the galactic centre would be so bright that it would turn night into

day.

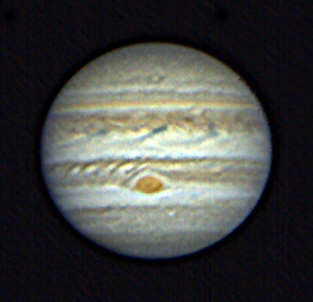

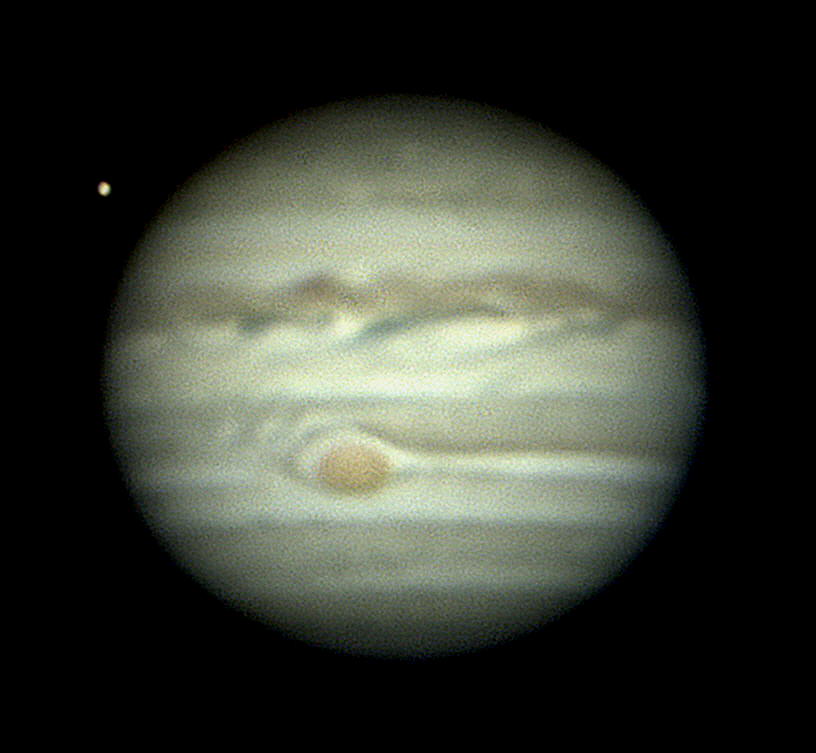

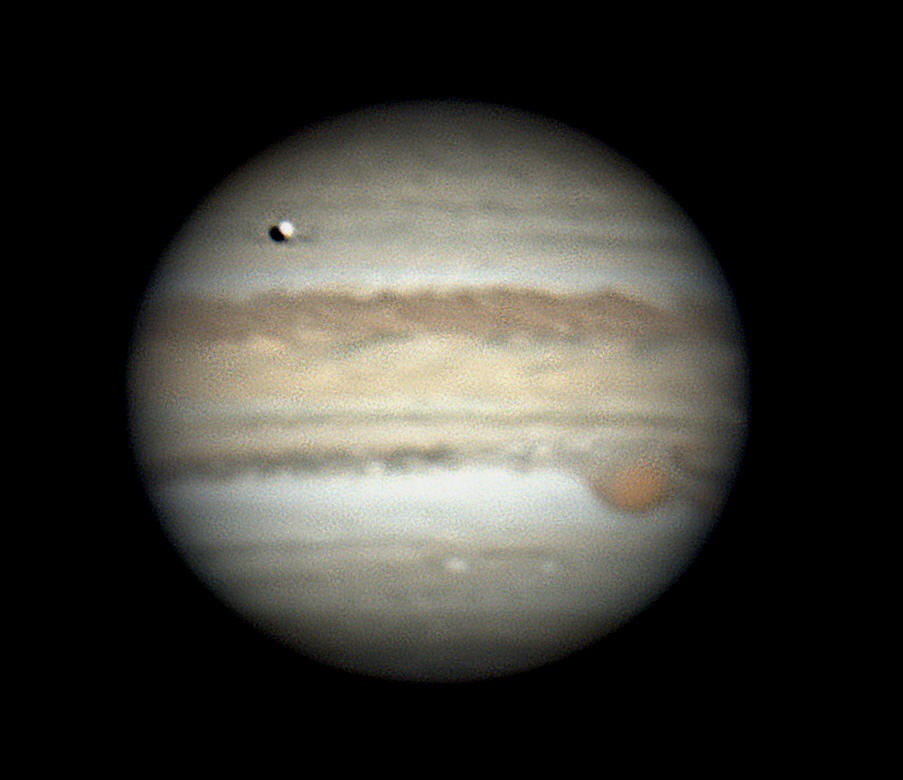

Jupiter near opposition in 2017

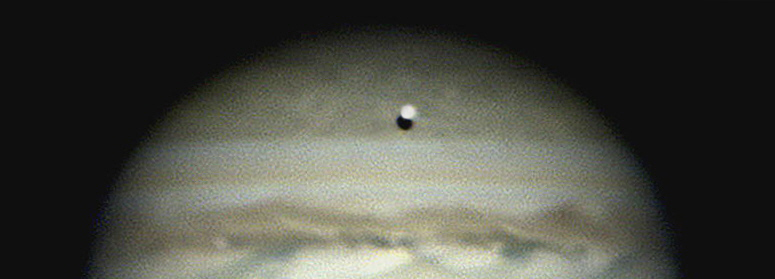

Jupiter as

photographed from Nambour on the evening of April 25, 2017. The images were

taken, from left

to right, at 9:10, 9:23, 9:49, 10:06 and 10:37 pm. The rapid

rotation of this giant planet in a little under 10

hours is clearly seen. In the

southern hemisphere, the Great Red Spot (bigger than the Earth) is prominent,

sitting within a 'bay' in the South Tropical Belt. South of it is one of the

numerous White Spots. All of these

are features in the cloud tops of Jupiter's

atmosphere.

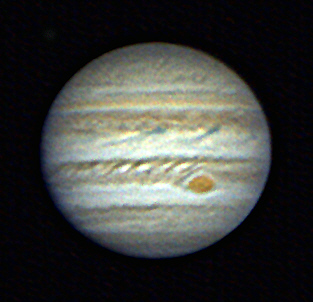

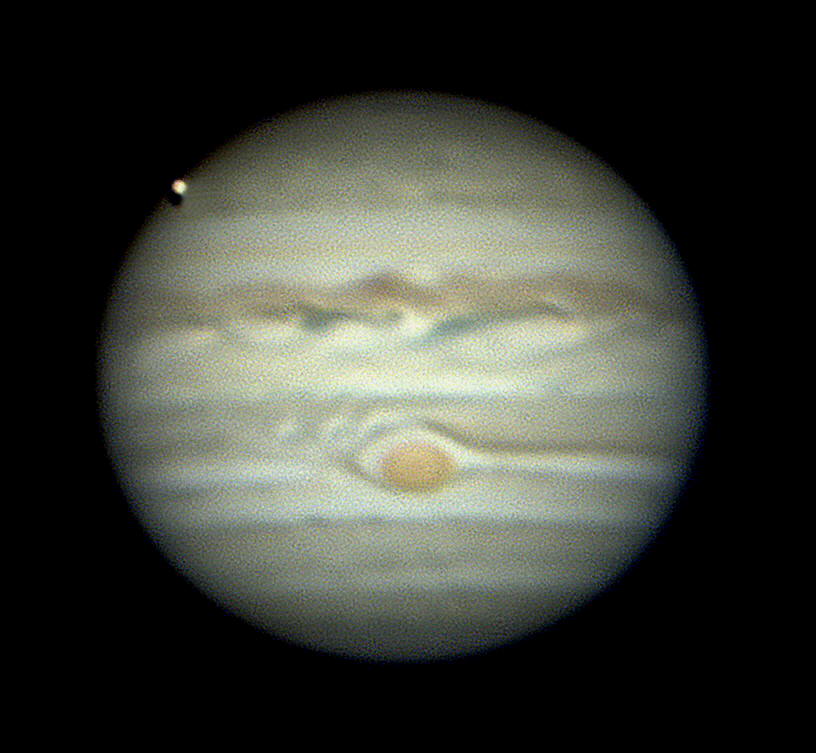

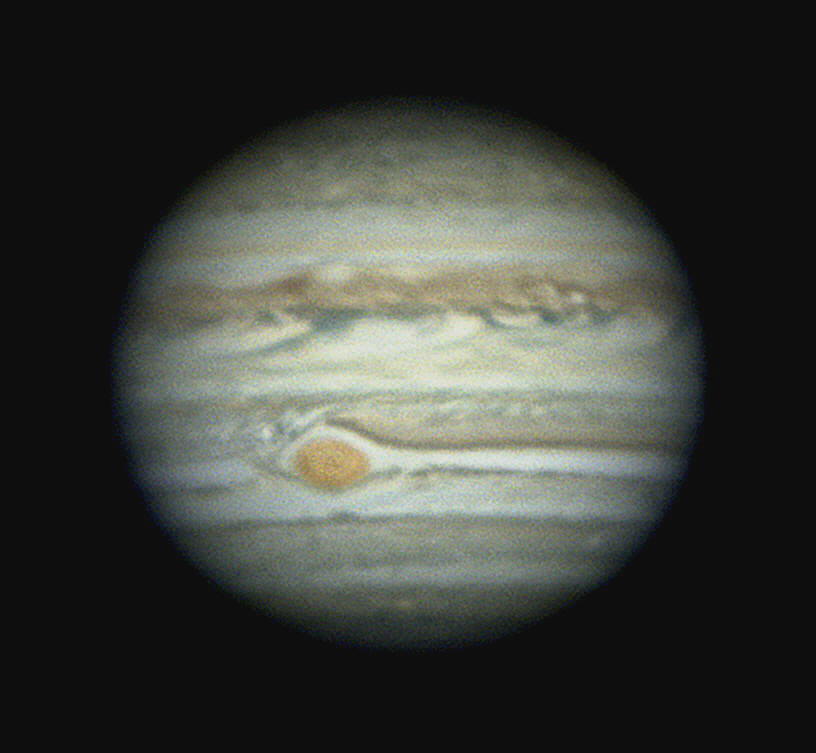

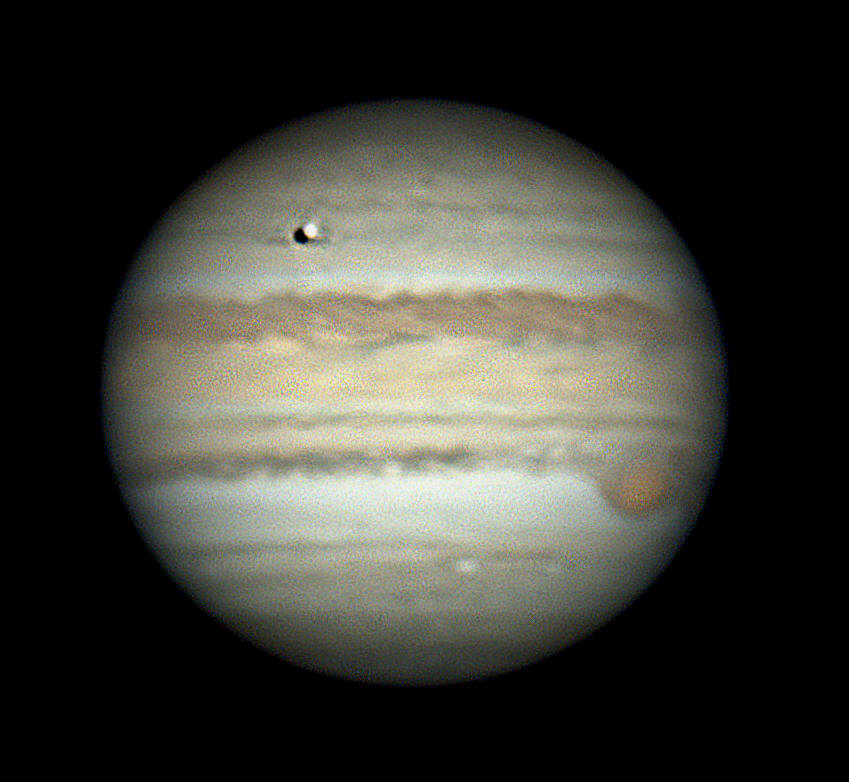

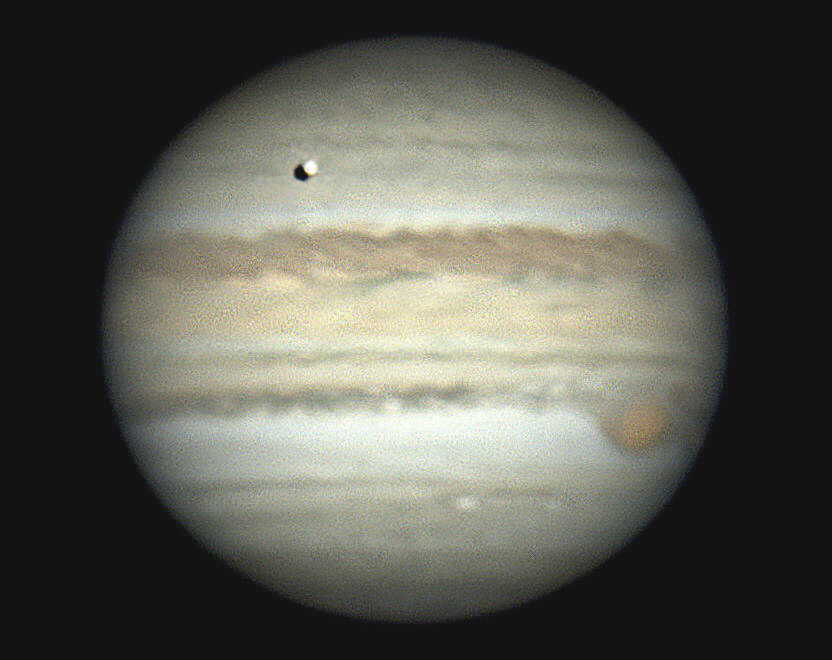

Jupiter as it appeared at 7:29 pm on July 2, 2017. The Great Red Spot is in a

similar position near Jupiter's

eastern limb (edge) as in the fifth picture in

the series above. It will be seen that in the past two months

the position of

the Spot has drifted when compared with the festoons in the Equatorial Belt, so

must rotate

around the planet at a slower rate. In fact, the Belt enclosing the

Great Red Spot rotates around the planet

in 9 hours 55 minutes, and the

Equatorial Belt takes five minutes less. This high rate of rotation has made

the

planet quite oblate. The prominent 'bay' around the Red Spot in the five earlier

images appears to be

disappearing, and a darker streak along the northern edge

of the South Tropical Belt is moving south.

Two new white spots have developed

in the South Temperate Belt, west of the Red Spot. The five upper

images were taken near opposition, when the Sun was directly behind the Earth and

illuminating all of

Jupiter's disc evenly. The July 2 image was taken just four

days before Eastern Quadrature, when the

angle from the Sun to Jupiter and back

to the Earth was at its maximum size. This angle means that

we see a tiny amount

of Jupiter's dark side, the shadow being visible around the limb of the planet

on

the left-hand side, whereas the right-hand limb is clear and sharp. Three of

Jupiter's Galilean satellites

are visible, Ganymede to the left and Europa to

the right. The satellite Io can be detected in a transit of

Jupiter, sitting in

front of the North Tropical Belt, just to the left of its centre.

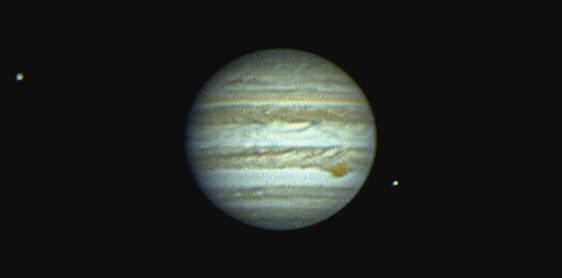

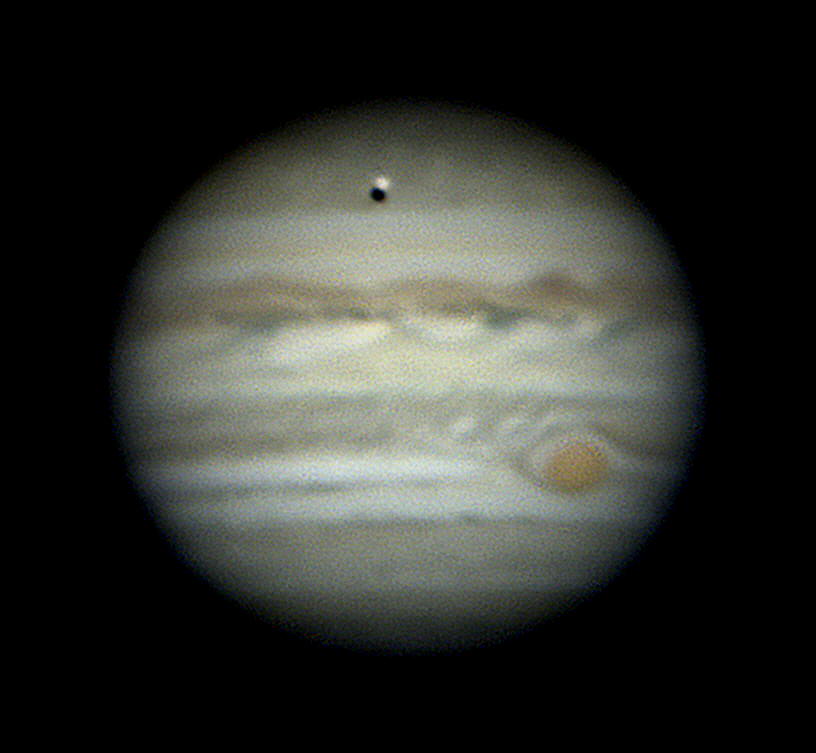

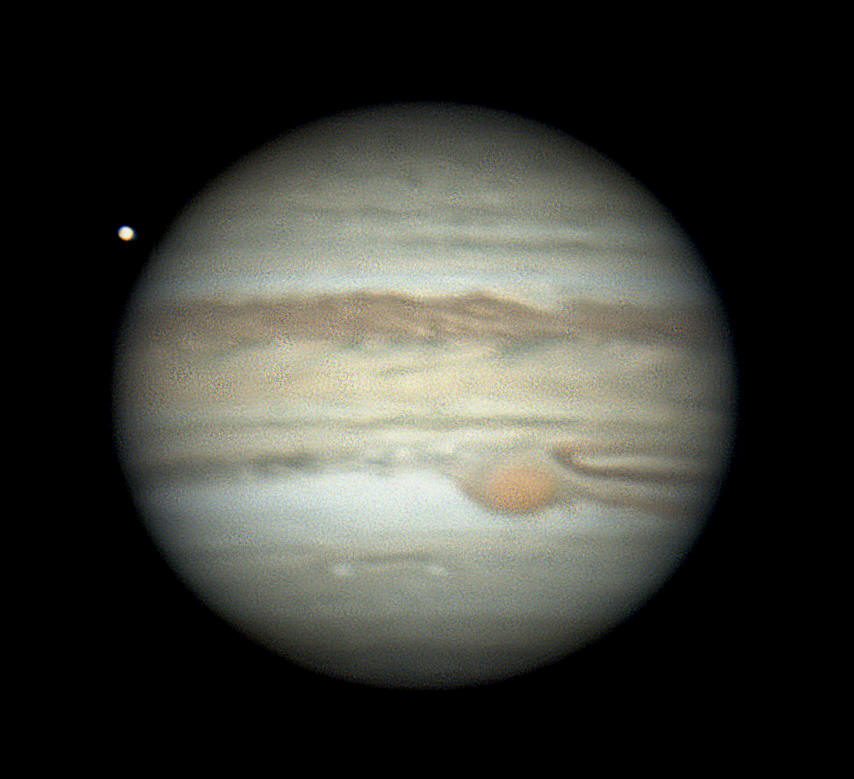

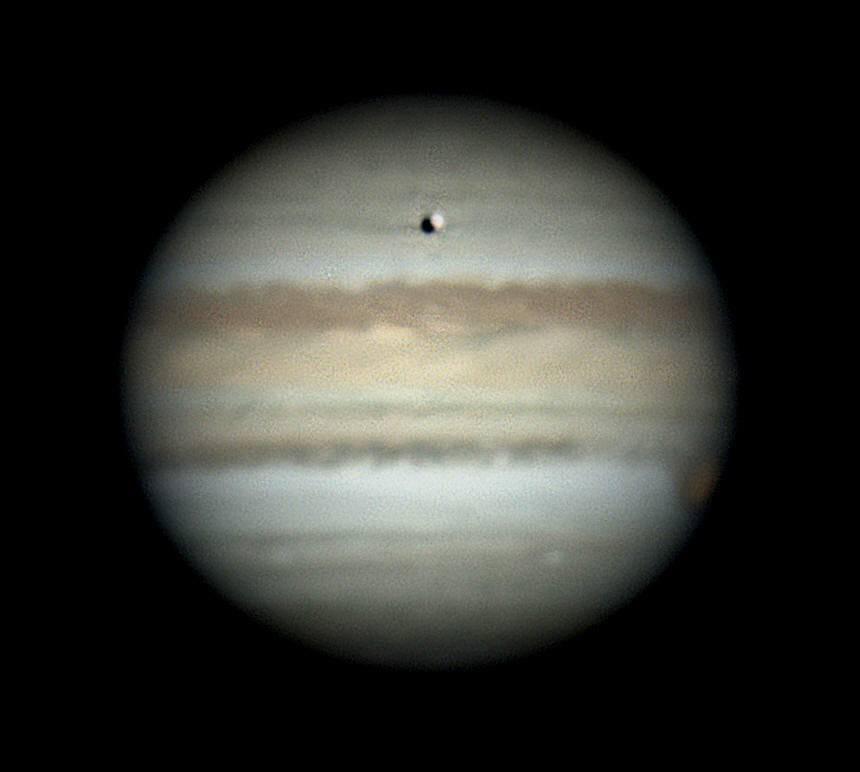

Jupiter at opposition

on May 9, 2018

Jupiter reached opposition on May 9, 2018 at 10:21 hrs, and the above photographs were

taken that evening,

some ten to twelve hours later. The first image above was

taken at 9:03 pm, when the Great Red Spot was

approaching Jupiter's central

meridian and the satellite Europa was preparing to transit Jupiter's disc.

Europa's transit began at 9:22 pm, one minute after its shadow had touched

Jupiter's cloud tops. The second

photograph was taken three minutes later at 9:25

pm, with the Great Red Spot very close to Jupiter's central meridian.

The third photograph was taken at 10:20 pm, when Europa was approaching

Jupiter's central meridian.

Its dark shadow is behind it, slightly below, on the

clouds of the North Temperate Belt. The shadow is partially

eclipsed by Europa itself. The fourth

photograph at 10:34 pm shows Europa and its shadow well past the

central meridian. Europa is

the smallest of the Galilean satellites, and has a diameter of 3120 kilometres.

It is ice-covered, which accounts for its brightness and whitish colour.

Jupiter's elevation above the horizon

for the four photographs in order was 50º,

55º, 66º and 71º. As the evening progressed, the air temperature

dropped a

little and the planet gained altitude. The 'seeing' improved slightly, from Antoniadi IV to Antoniadi III.

At the time of the photographs, Europa's angular diameter

was 1.57 arcseconds. Part of the final

photograph is enlarged below.

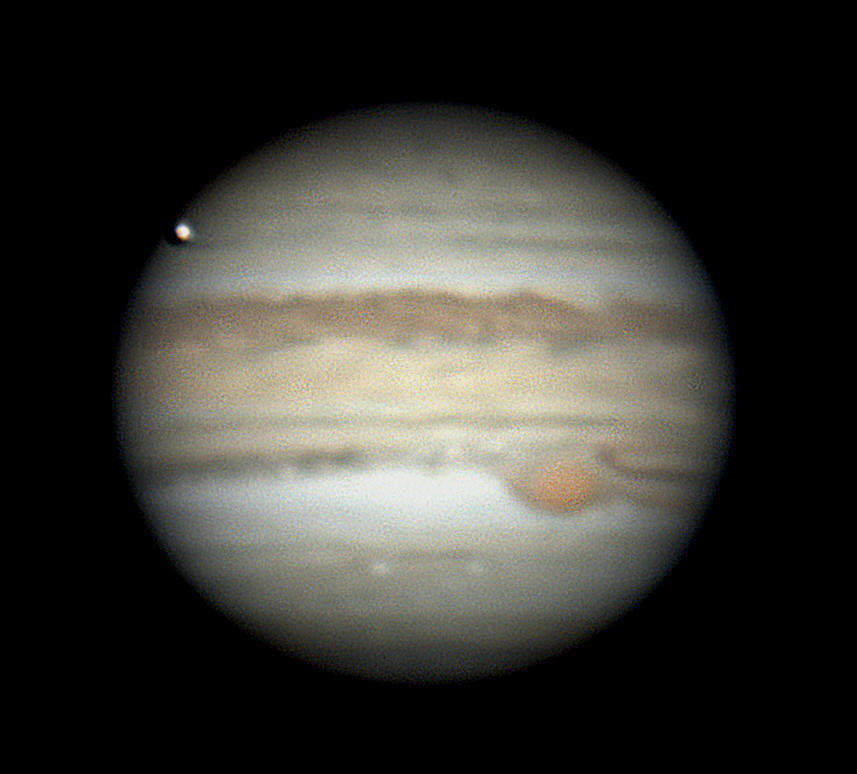

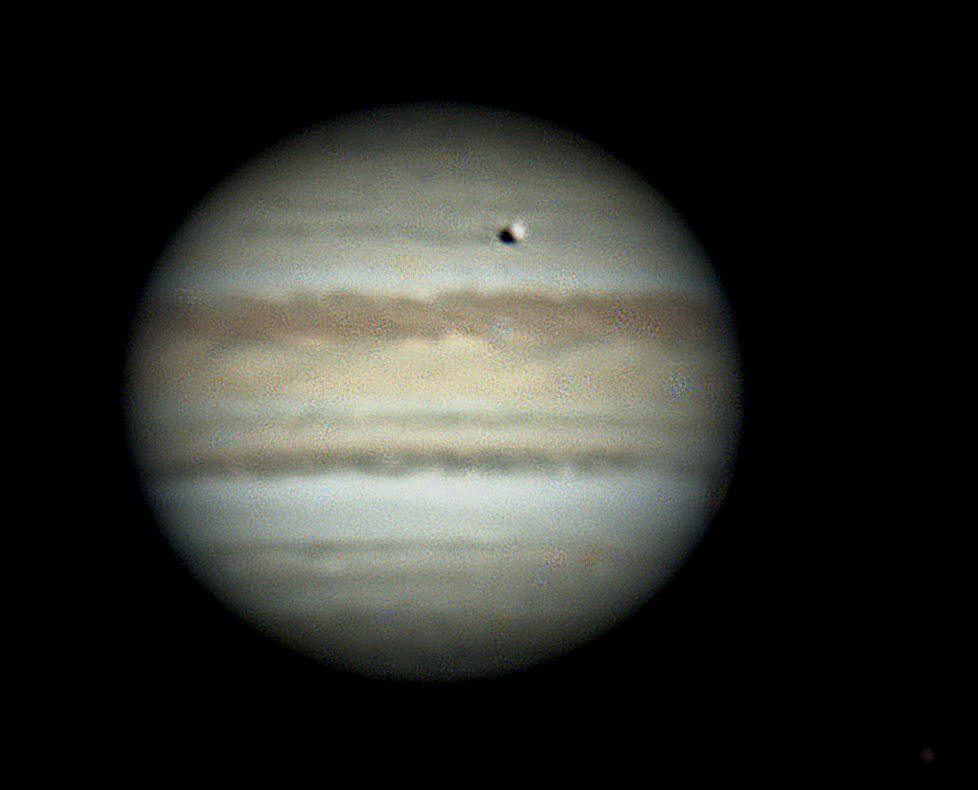

Jupiter at 11:34 pm on May 18, ten days later. Changes in the rotating cloud

patterns are apparent,

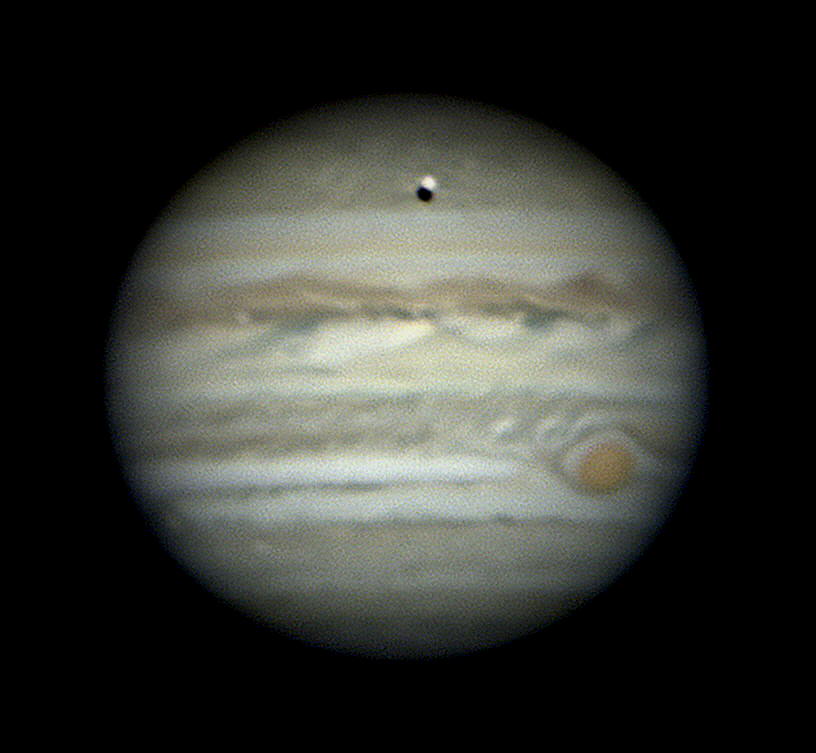

Jupiter at opposition on June 11, 2019

as some cloud bands rotate faster than others and

interact. Compare with the first photograph in

the line of four taken on May 9.

The Great Red Spot is ploughing a furrow through the clouds of the

South

Tropical Belt, and is pushing up a turbulent bow wave.

The third photograph was taken at 10:41 pm, when Europa was

about a third of its way across Jupiter.

There have been numerous alterations to Jupiter's belts and spots over the thirteen months since the 2018

some

twenty to twenty-two hours later. The first image above was

taken at 10:01 pm, when the Great Red Spot

was leaving Jupiter's central meridian and the satellite Europa was preparing to transit Jupiter's disc.

Europa's transit began at 10:11 pm, and its shadow touched Jupiter's cloud tops

almost simultaneously.

Europa was fully in transit by 10:15 pm. The second photograph was taken two minutes later at

10:17

pm,

with the Great Red Spot heading towards Jupiter's western limb.

Its dark shadow is trailing it, slightly below, on the clouds of the North Temperate Belt. The shadow is

partially eclipsed by Europa itself. The fourth

photograph at 10:54 pm shows Europa and its shadow about

a quarter of the way across. This image is enlarged below. The fifth photograph shows Europa on Jupiter's

central meridian at 11:24

pm, with the Great Red Spot on Jupiter's limb.

The sixth photograph taken at 11:45 pm shows Europa about two-thirds of the way through its transit,

and the

Great Red Spot almost out of sight. In this image, the satellite Callisto may be

seen to the lower

right of its parent planet. Jupiter's elevation above the horizon for the six photographs in order was 66º,

70º,

75º, 78º, 84º and 86º. As the evening progressed, the 'seeing' proved quite variable.

opposition. In particular, there have

been major disturbances affecting the Great Red Spot, which appears

to be slowly

changing in size or "unravelling".

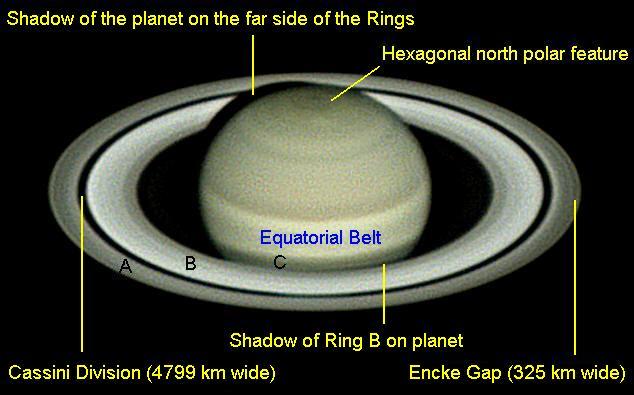

Saturn

Right: Over-exposed

Saturn surrounded by its satellites Rhea, Enceladus, Dione, Tethys and Titan -

February 23/24, 2009.

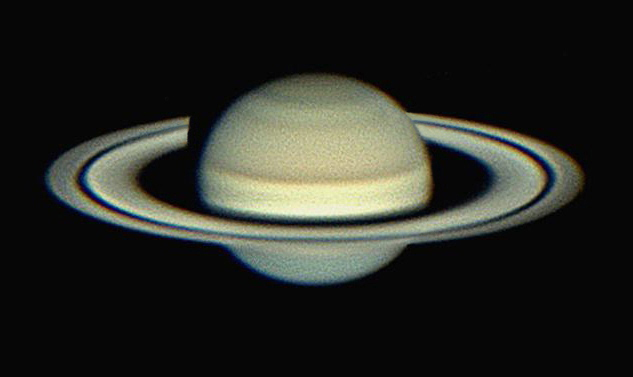

Saturn with its Rings wide open on July 2, 2017. The shadow of its globe can be

seen on the far side of

the Ring system. There are three main concentric rings:

Ring A is the outermost, and is separated from

the brighter Ring B by a dark gap

known as the Cassini Division, which is 4800 kilometres wide, enough

to drop

Australia through. The innermost parts of Ring B are not as bright as its

outermost parts. Inside

Ring B is the faint Ring C, almost invisible but

noticeable where it passes in front of the bright planet as a

dusky band.

Spacecraft visiting Saturn have shown that there are at least four more Rings,

too faint and

tenuous to be observable from Earth, and some Ringlets. Some of

these extend from the inner edge of

Ring C to Saturn's cloudtops. The Rings are

not solid, but are made up of countless small particles,

mainly water ice with

some rocky material, all orbiting Saturn at different distances and speeds.

The

bulk of the particles range in size from dust grains to car-sized chunks.

T

he photograph above was taken when Saturn was close to opposition, with the Earth between Saturn

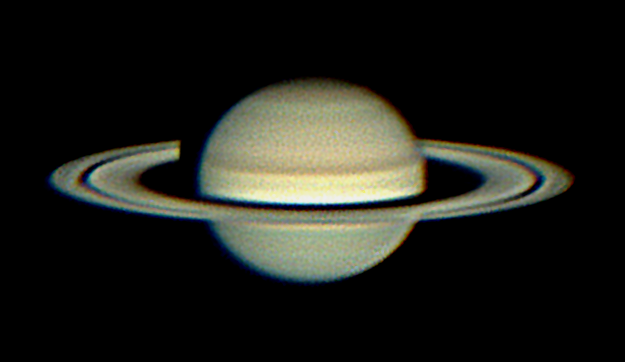

The change in aspect of Saturn's rings is caused by the plane of the ring system being aligned with Saturn's equator, which is itself tilted at an angle of 26.7 degrees to Saturn's orbit.

As the Earth's orbit around the Sun is in much the same plane as Saturn's, and

the rings are always tilted in the same direction in space, as we both orbit the Sun, observers on Earth see the configuration of the rings change from wide open (top large picture) to half-open

(bottom large picture) and finally to edge on (small picture above). This cycle is due to Saturn taking 29.457 years to complete an orbit of the Sun, so the

complete cycle from

"edge-on (2009) →

view of Northern hemisphere, rings half-open (2013) → wide-open (2017) → half-open (2022) →

Neptune

Neptune, photographed from Nambour on October 31, 2008

Pluto

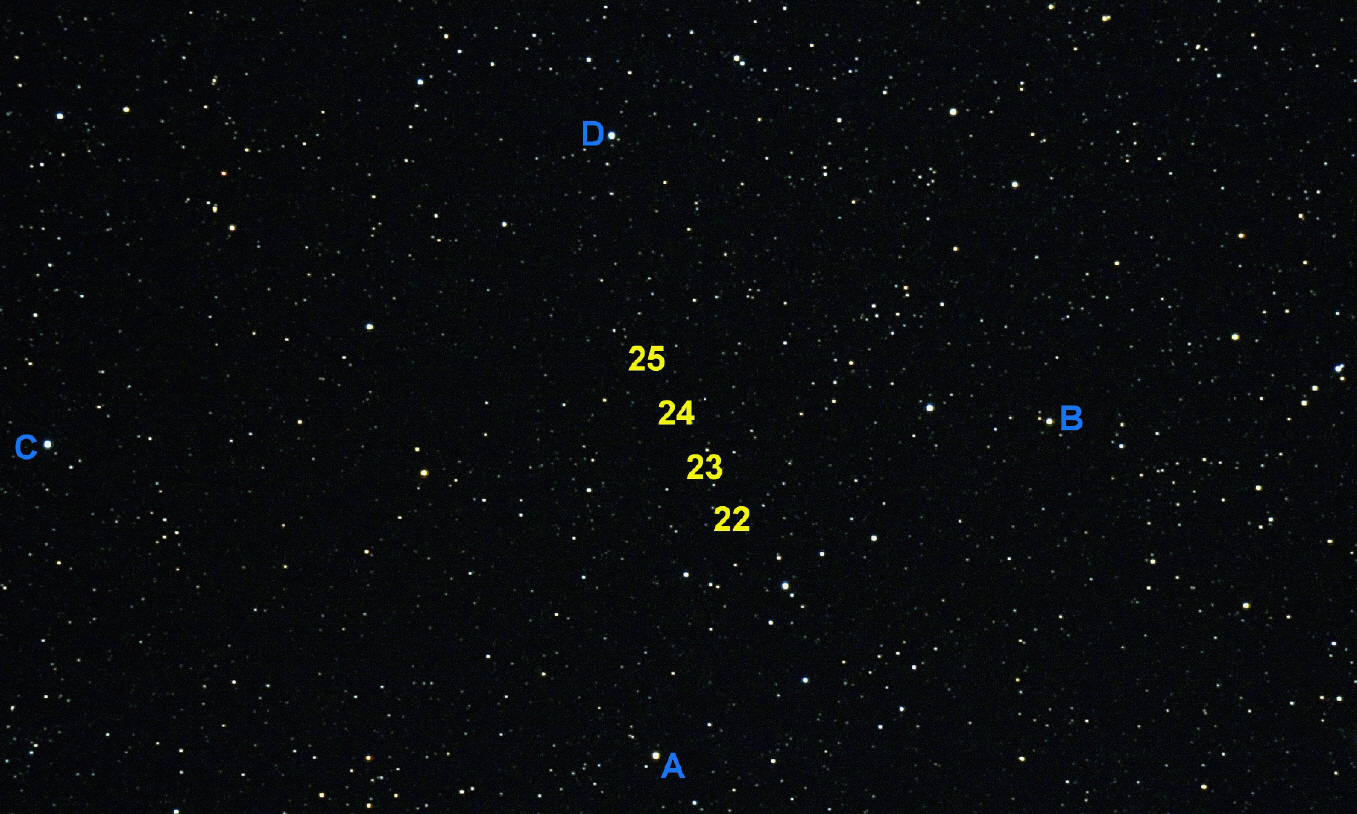

The movement of the dwarf planet Pluto in two days, between 13 and 15 September, 2008. Pluto is the

one object that has moved. Width of field: 200 arcseconds

This is a stack of four images, showing the movement of Pluto

over the period October 22 to 25, 2014.

Pluto's image for

each date appears as a star-like point at the upper right corner of the numerals.

The four are equidistant points on an almost- straight line. Four eleventh magnitude field stars are

identified.

A

is GSC 6292:20, mv

= 11.6.

B

is GSC 6288:1587, mv

= 11.9.

C

is GSC 6292:171,

mv

= 11.2.

Comet 17P / Holmes, October - December 2007

Comet 17P/Holmes is an extremely faint periodic comet that returns every 6.88 years without anyone taking much notice. Its arrival last year gained it world-wide attention, for it exploded on 24 October 2007. A vast sphere of dust and debris was ejected in an ever-growing cloud. Though the comet’s head is only some tens of kilometres across, the cloud rapidly reached the size of Jupiter by November 9 grew larger than the Sun. It has continued to enlarge until it exceeded two million kilometres in diameter.

Before the eruption, the comet could only be seen through large telescopes, but the explosion caused it to brighten a millionfold within 36 hours, making it an obvious naked-eye object. It is possible that there could be a second explosion, as occurred in 1892 and led to its discovery by Edwin Holmes.

Since the explosion was first detected, the comet expanded dramatically, to become the largest object in the solar system. It reached a size in the night sky a little larger than the diameter of the Moon. How a small comet could produce such an enormous cloud has not yet been explained.

In mid-November 2007, Comet Holmes experienced a ‘disconnection event’ - its faint, beautiful blue ion tail became detached from its head. Comet tails can be disconnected by gusts of solar wind which trigger magnetic storms around the comet similar to the geomagnetic storms which cause aurorae on Earth. Such a storm and disconnection was observed earlier this year in the tail of Comet Encke.

Was it really the largest object in the Solar System? In diameter, yes, but of course the Sun is the most massive object by several orders of magnitude. Some comets produce tails many millions of kilometres long, so they would be longer, but not 'bigger'. Photographs taken from Starfield Observatory, Nambour appear below.

This image and those following are all taken with the same equipment and have

the same plate scale,

except when indicated otherwise. They therefore show how the ejecta cloud surrounding the

nucleus has

expanded from night to night. The sphere of ejecta surrounding the comet's nucleus is most clearly defined

in

the direction of the Sun, In the picture above this direction is towards the

lower right. The magnitude 11.4

star GSC

3321:602 can be seen shining through the cloud at upper left. The diameter of

the expanding

cloud had reached 15 arcminutes and was still growing.

In the remaining images, the direction of the Sun is to the right.

This

image was taken ten nights later,

on 13

November. The cloud of dust surrounding the nucleus is much larger - in fact the

cloud itself was

larger than the Sun and appeared in the sky about the same size

as the Full Moon.

This

image was taken three nights later, just

after midnight on 17

November. The cloud of dust surrounding

the nucleus continues to grow, and the

comet is now the largest object in the Solar System. It appeared to

the

unaided eye like a faint ghost of the Full Moon. The bright star at lower left

is Mirfak, a yellow-white F5

star of magnitude 1.79.

This

image was taken two nights later, on November 19. The coma of Comet Holmes

appears to swallow

the much more distant star Mirfak. At this stage the comet is

fading, and becoming swamped by

moonlight from the waxing gibbous Moon.

This

image was taken ten nights later, on November 29. The cloud is still

expanding, and has reached

a diameter of 46 arcminutes (cf approximately 30

arcminutes for the Full Moon. A newly developing tail

can be seen extending from

the spherical cloud to the left-hand margin.

This

image was taken at the prime focus of the RCOS reflector, and has a much larger

plate scale than

the other images above. It shows the interior of the ejecta

cloud, which fills the frame and has now

become the comet's coma. The nucleus or

head is just right of centre, and the beginnings of the tail

stream off to the

left. Image acquired on December 3.

Comet 2006 P1 (McNaught), January - February 2007

Comet McNaught provided a magnificent display in early 2007, the best since the 1910 apparition of Halley's Comet. At its brightest, the head outshone nearby Venus, and the tail developed great fan-shaped streamers of dust and gas that spread over a large span of the night sky. The following images were taken on January 20 and 21, when there was a break in persistent overcast weather. Thanks to Nambour Plaza's Digital Dog for careful processing.

Comet McNaught faintly appears out of the

twilight shortly after sunset. Photographed from the Maleny-

Conondale Road on

January 20.

As twilight fades, Comet McNaught becomes easily seen.

The comet becomes clearly visible

as darkness falls.

The great tail does

not become visible until twilight fades. Unfortunately this happens after the

comet's

head has passed below the horizon. Photographed from Starfield

Observatory in Nambour on January 21.

The house lights in the foreground are at

Image Flat. The short curved lines in the sky are star trails

caused by the

Earth's rotation.

The full extent of the tail is

revealed after darkness falls. A faint line of dots crossing the frame is the

trail left by the strobe lights of the local rescue helicopter on its flight

path to the Nambour Hospital.

There are over a dozen synchronic

bands or streamers visible in the comet's tail

in this photograph.

The lights on the skyline are private homes built on Kureelpa Falls Road, on the edge of the Highworth

Range escarpment. The Dulong

Lookout is at the left margin. The brightest star trail at upper right was

made by the first magnitude star Fomalhaut. The bright star behind the comet's

tail (above left centre

of photograph) is the star Al Nair in the constellation Grus. Taken from Starfield Observatory

with a

standard lens which has a field width of 43 degrees.

By February 6 the synchronic

bands have merged into a wide, triangular fan tail covering an angle of

about 55

degrees.

The star just below the comet's coma (the glowing gas and dust surrounding the

nucleus)

is SAO 247006, magnitude 7.47. The faintest stars on this image are of

magnitude 13. None of these

stars is visible to the unaided eye. Taken from Starfield Observatory - the field width is 4.5 degrees.

Comet 2007 N3 (Lulin), February - March 2009

Comet Lulin was

discovered in 2007 at Lulin Observatory by a collaborative team of Taiwanese and Chinese astronomers. It moved rapidly from Scorpius to Gemini, the head reaching a magnitude of 5. It had bright ion and dust tails, and an anti-tail.

Comet 46P / Wirtanen, November - December 2018

In December 2018, Comet 46P/Wirtanen swept past Earth, making one of

the ten closest approaches of a comet to our planet since 1960. It became

faintly visible to the naked eye for weeks.

Although Wirtanen's nucleus is only 560 metres across, its emerald green atmosphere

appeared larger than the full Moon, and it was an increasingly easy target for binoculars

and small telescopes. It reached its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) on December 12, and then

headed towards Earth. It passed the Earth at a distance of 11.5 million kilometres (30 times as far away as the Moon) on December 16. Its

passage across the sky took it from the southern constellation of Fornax through

Eridanus, Cetus, Taurus and Auriga, making it an all-night object for observers

in the southern hemisphere. I

position was Right Ascension = 2 hrs 30 min 11 secs,

Declination = 21

the top of the picture. The nearest star to the comet's position, just to its left, is GSC 5862:549,

magnitude 14.1.

The spiral galaxy near the right margin is NGC 908.

The right-hand star in the yellow circle is SAO 167833,

magnitude 8.31.

9:05

pm. The comet's movement over the 52 minute period can be seen, the five images of the

comet

merging into a short streak.

It is heading towards the upper left corner of the image, and is brightening as

it approaches the Sun, with perihelion occurring on December 12. The images of the stars

in the five

exposures overlap

each other precisely. The length of the streak indicates that the comet is

presently

moving against the starry background at 1.6º per day.

The comet at 9:05 pm was at Right Ascension = 2 hrs 32 min 56 secs, Declination = 20º 27'

20".

The upper star in the yellow circle is SAO 167833, magnitude 8.31, the same

one circled in the preceding

picture but with higher magnification.

eye, but easily visible through binoculars.

The Moon to: The Stars

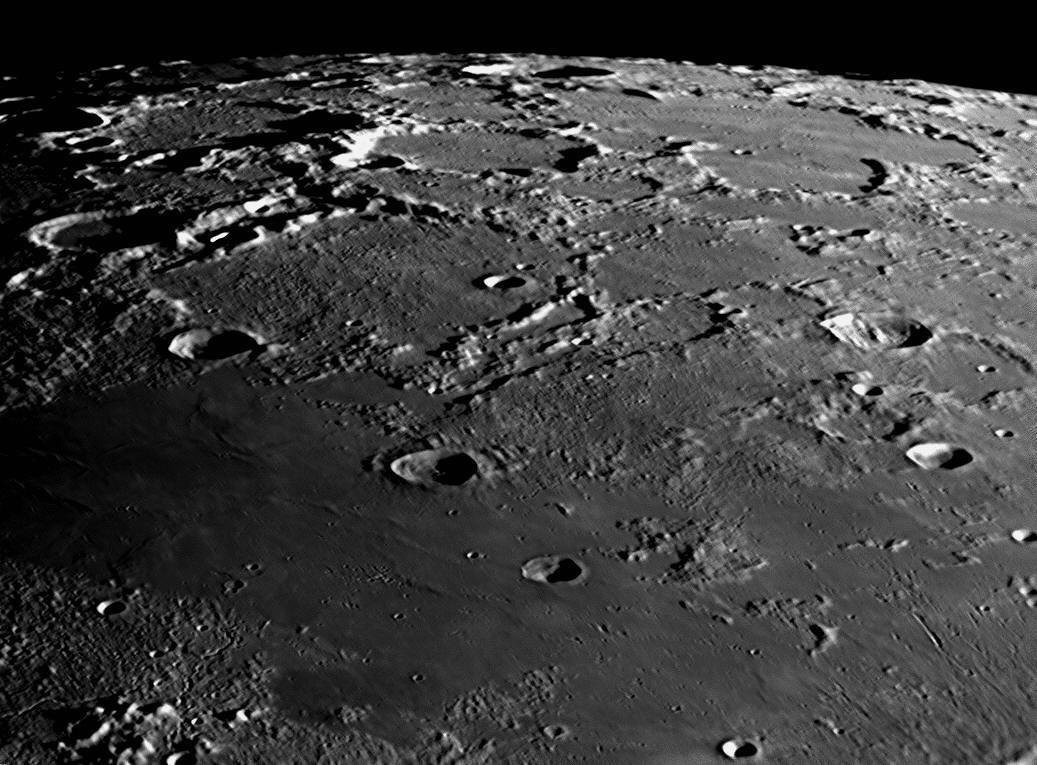

Below is a picture of the Moon's Mare Imbrium taken forty years ago on Kodachrome II colour slide film by the writer at the East Warwick Observatory, using a Celestron 14. Following this is a set of pictures taken with a digital video camera at Nambour from 2017 to the present.

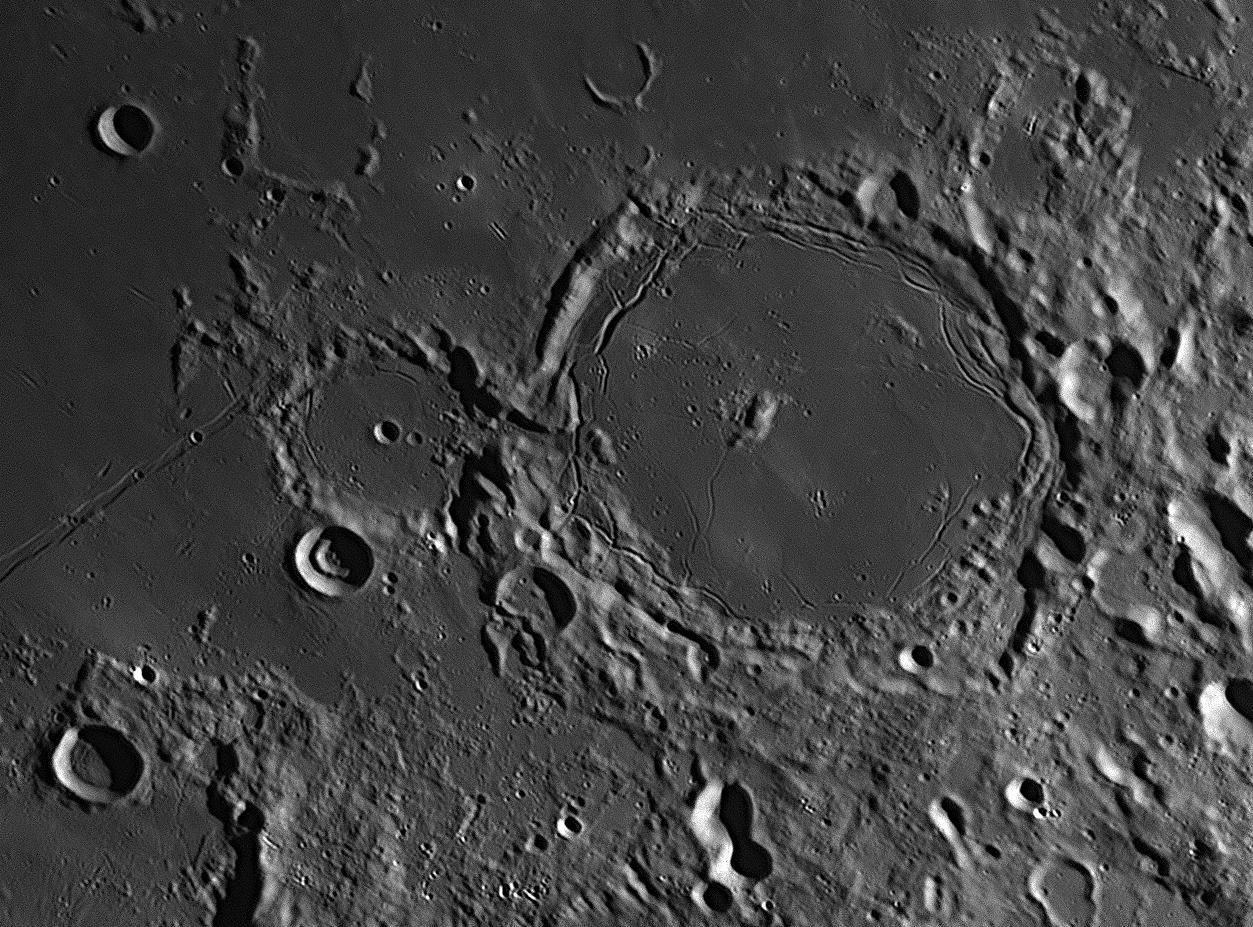

Mare Imbrium, with the large

walled plain Plato (centre left, 100 km diameter) and the 130 km

long Alpine

Valley (centre right).

The following are digital images taken with the Alluna RC-20 at Starfield Observatory. The video cameras used are a ZWO ASI 120MM-S, ZWO ASI 290MM and ZWO ASI 290 MC. The video streams of 2000 - 2500 frames are processed using AutoStakkert 3 and RegiStax 6.1 to produce still images.

The most delicate details visible in these images include the tiny craterlets on the floors of Plato and Archimedes, the Schröter's Valley rille and the Alpine Valley rille which averages only 600 metres across and 75 metres deep.

Moon at 8 days after

New. You may be able to find on this image some of the lunar features seen in

close-up in the following images.

Sunrise at the Moon's south pole.

Sunrise at the Moon's north pole.

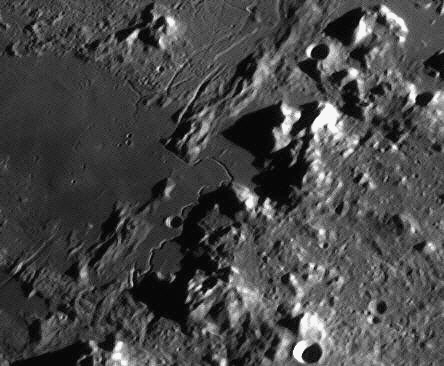

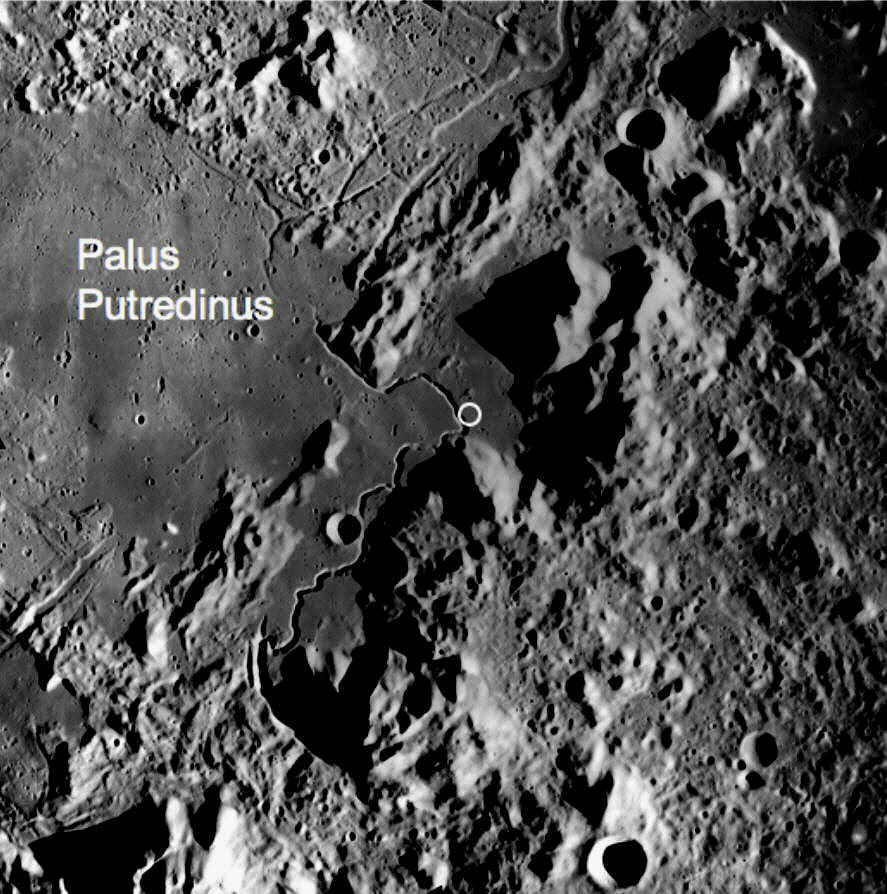

This area was photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on October 10,

2016. East (where the

Sun is rising) is to the right, north is to the top. The area is dominated by the

large walled plain Plato at upper left,

and the impact crater Cassini at lower

right. Between the two is a rugged mountainous area called the Alps,

to the west

of which is a large basin filled with solidified lava, called Mare Imbrium (the

Sea of Rains).

Most of the craters on the Moon larger than about 8 kilometres are named,

usually after famous philosophers

or scientists. In addition, the lava plains,

mountain ranges, peaks, shallow valleys (called 'rilles'), and other

notable

features have also received names, sometimes after places on the Earth. As there

are no rivers,

cities or countries on the Moon, these names help observers to

find their way around. The second picture

above shows some examples.

Plato in close-up. Five craterlets with diameters of 2 to

3 kilometres are visible inside it, as well as several smaller ones.

Sunrise over the 166

km long Vallis Alpes (Alpine Valley). It has a maximum width of 10 km. A

delicate rille runs

One day later.

along the entire length. The rille has an average width of 600 metres and an

average depth of 78 metres.

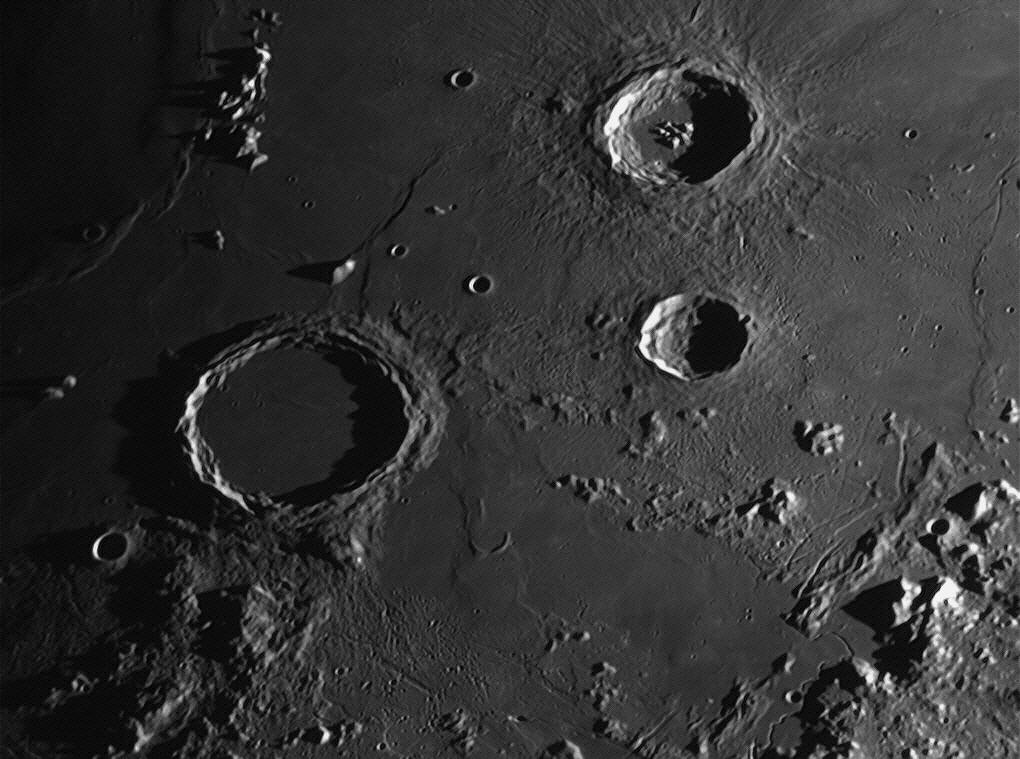

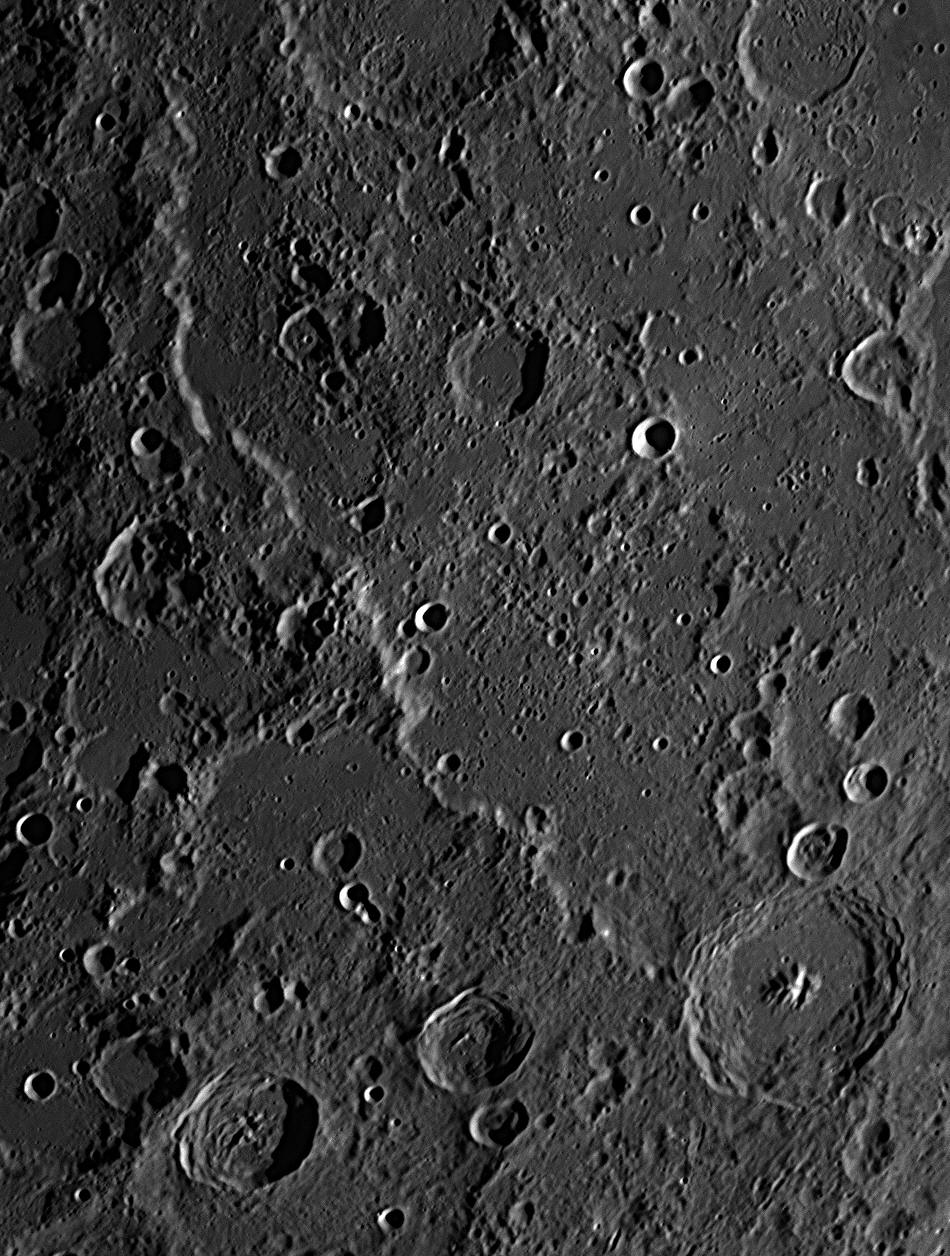

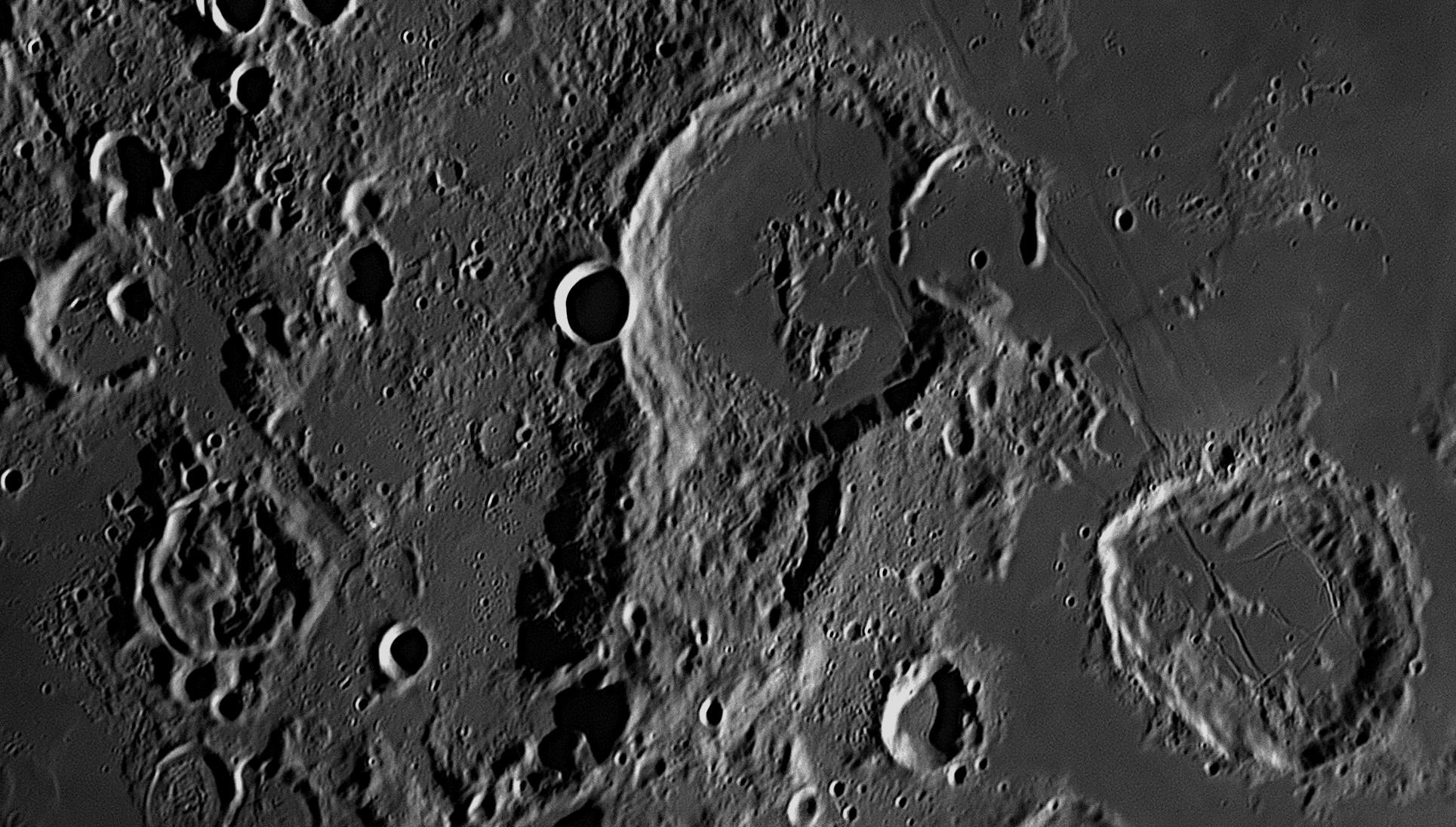

This well-known trio dominates the south-eastern quadrant of Mare Imbrium. The

craters are Archimedes (left),

Aristillus (top right) and Autolycus (lower right). The Fresnel Rilles and

Hadley Rille are in the lower right-hand corner.

Some small craterlets dot the flat floor of Archimedes. The complex of mountains

at upper left is called the Spitzbergen.

Close-up of Archimedes, 85 km in diameter. The smallest craterlets visible are less than 1 km in diameter.

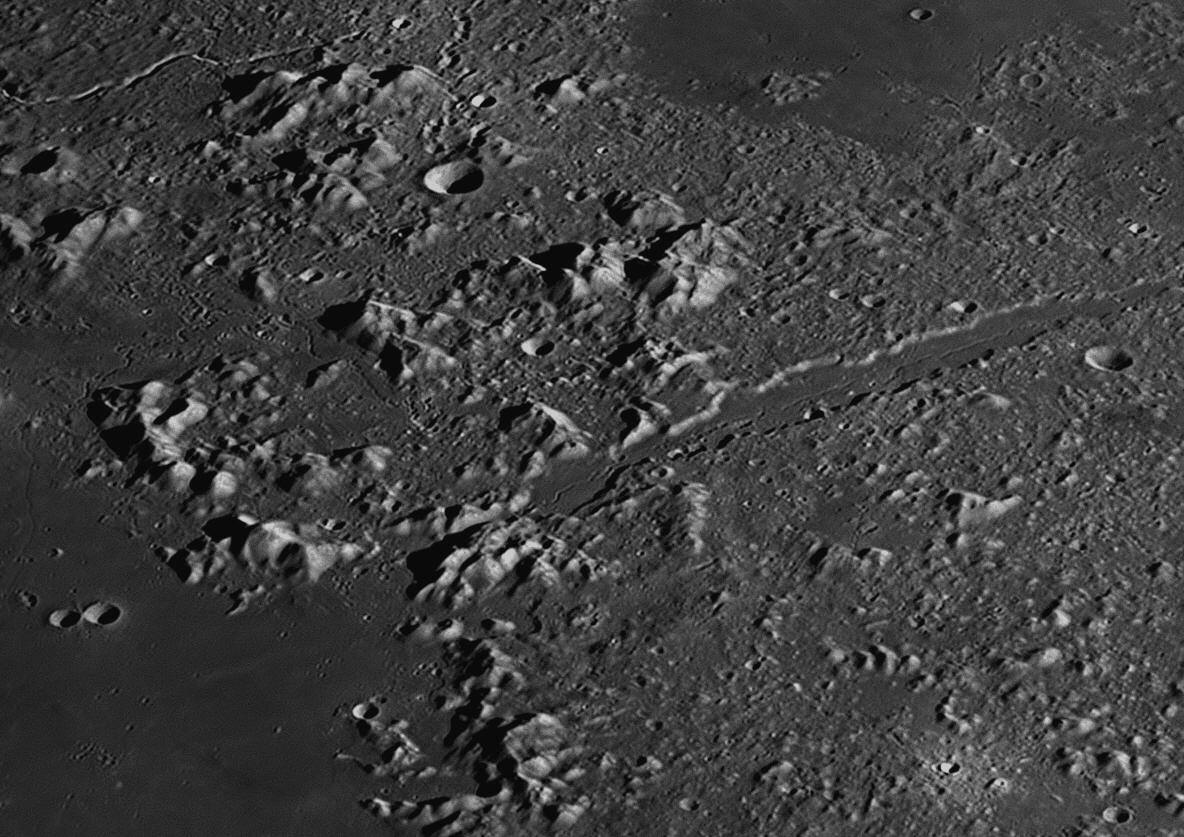

Sunrise on the Apennines: the crater Eratosthenes and the Montes Apenninus on the Moon,

photographed from Nambour on August

1, 2017.

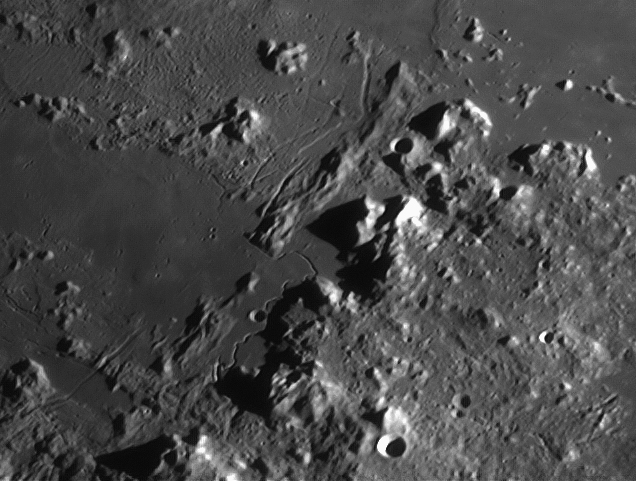

This area was photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on August 2, 2017.

East (where

the Sun is rising) is to the right, north is to the top.

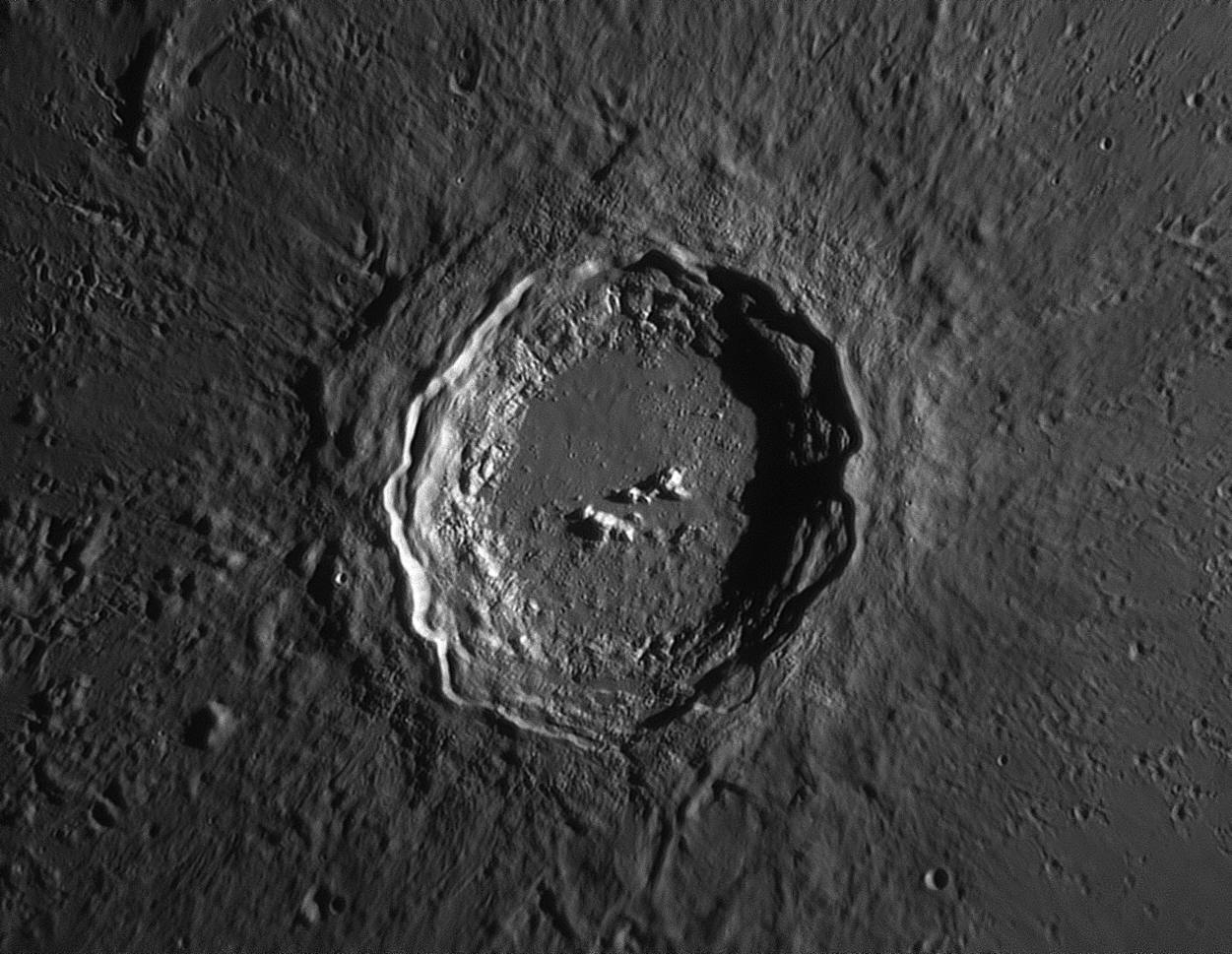

Eratosthenes is the crater at top right, Copernicus

is at lower left.

The damaged landscape and debris field caused by rubble from the Copernicus impact

is at centre,

and

the ghost crater Stadius can be faintly seen at lower right.

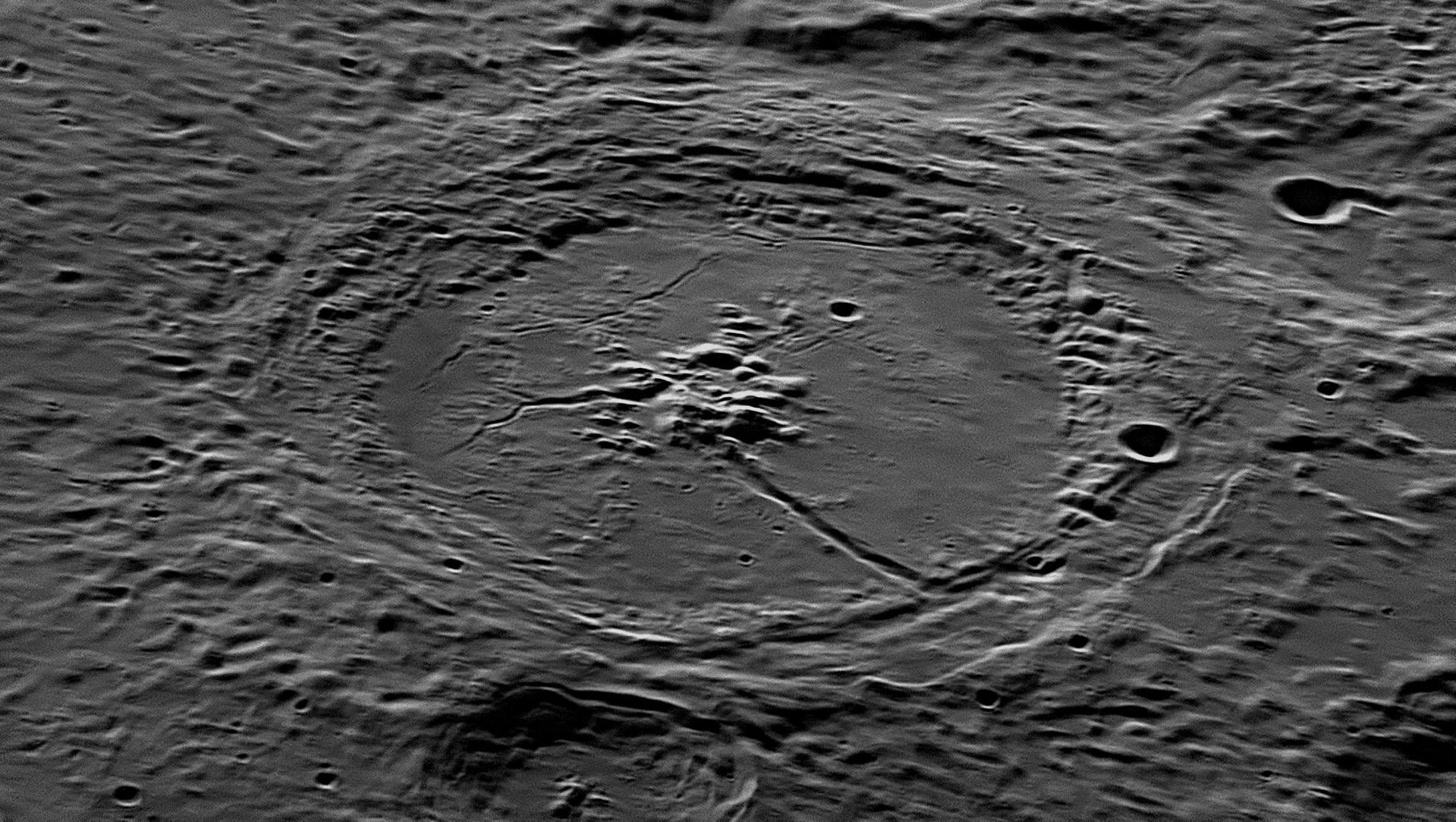

This image adjoins the one above.

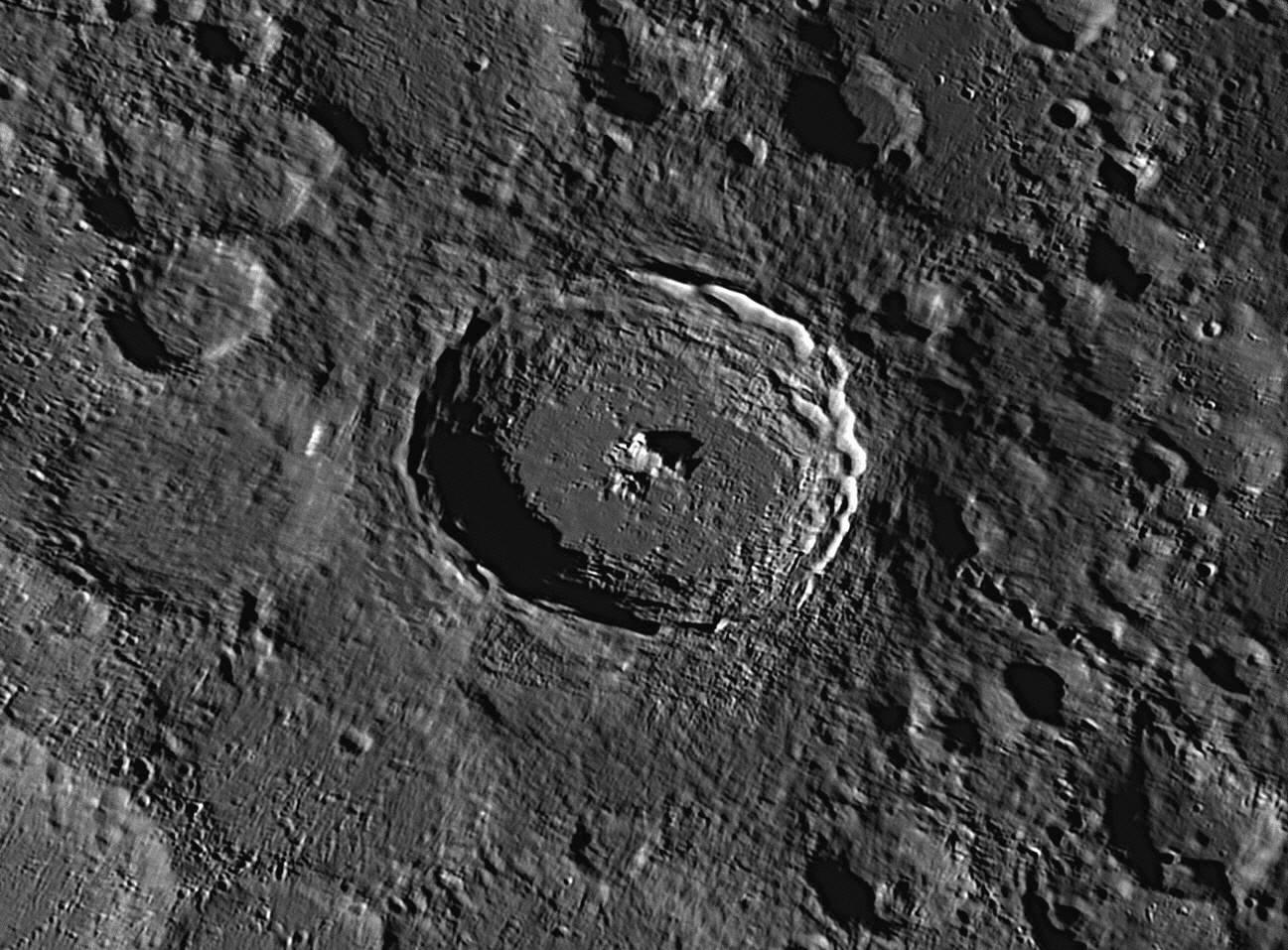

The young crater Copernicus has a diameter of 95 km and is

3.75 km

deep.

Photographed on August 2, 2017.

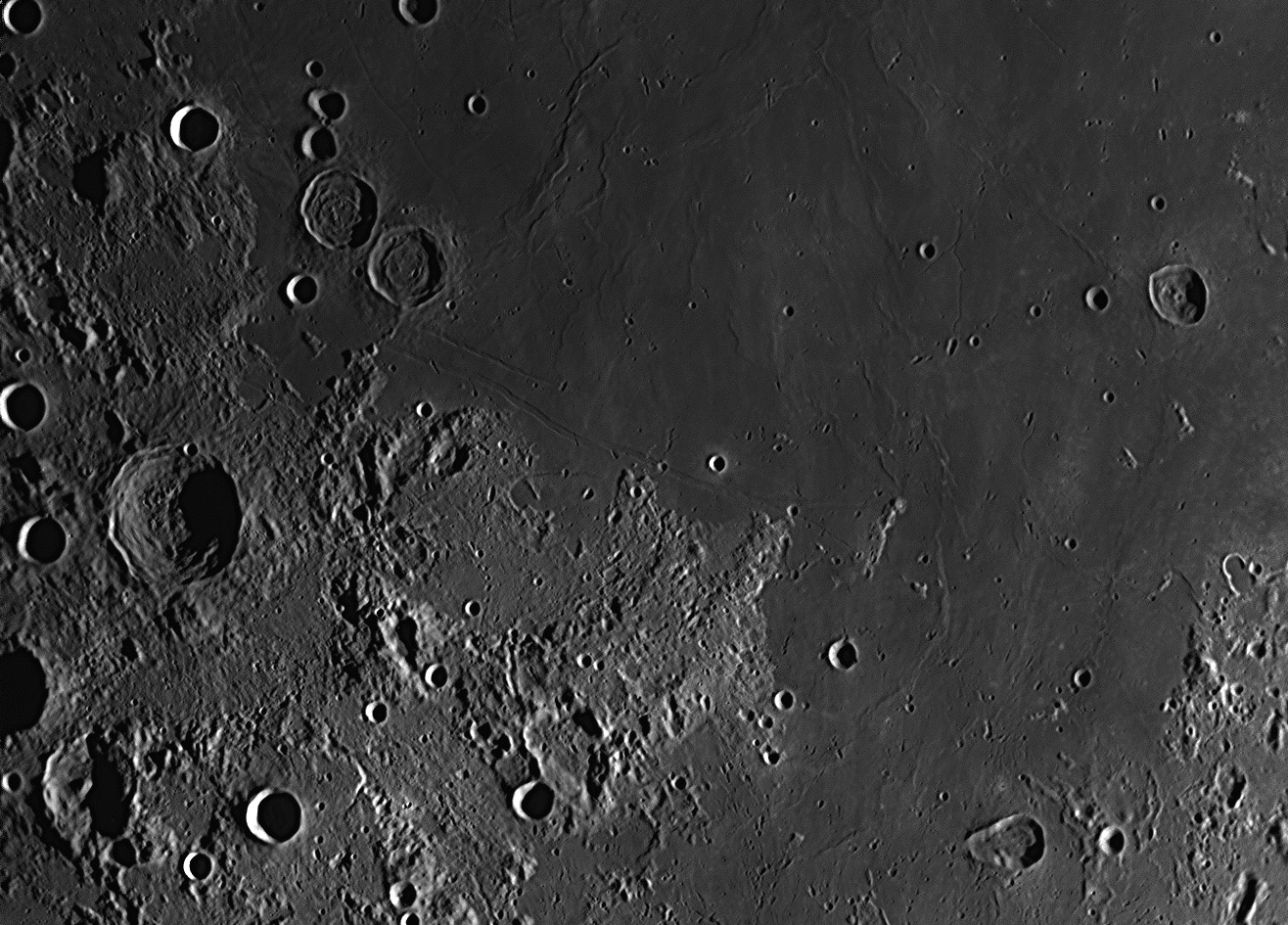

This area shows Tranquility Base, site of the landing by Apollo 11's lunar

module on July 21, 1969.

It was photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on July 30,

2017. East (where the Sun is

rising) is to the right, north is to the top. The largest crater in the image

above is near the centre of the

left margin, and is

called Delambre. The deformed crater towards bottom right is named Torricelli.

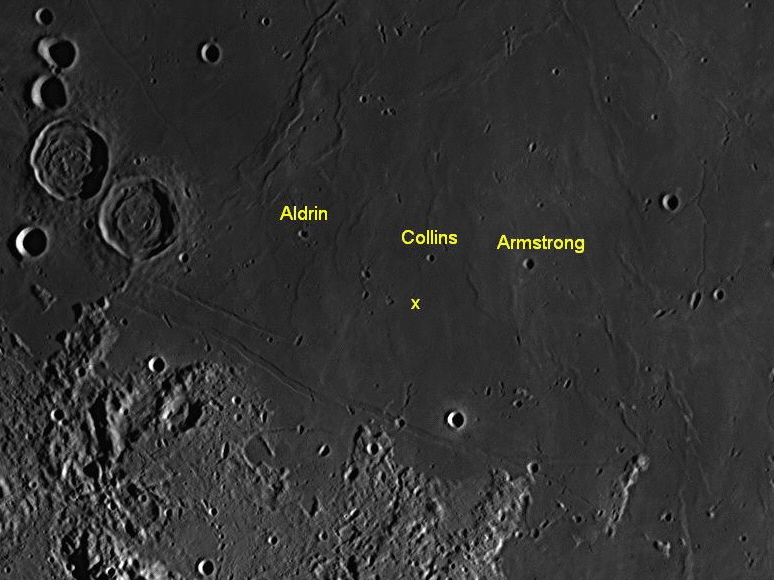

This is an enlargement of the previous image.

The landing site is shown by an '

x

'. Three craterlets have

been

officially named after the astronauts. Armstrong is 4.6 km in diameter,

Collins is 2.4 km,

and

Aldrin is 3.4 km.

The lunar module's landing approach was from the east (right).

Hadley Rille and its environs, where Apollo 15 landed. The Rille varies between

1 and 1.5 km in width,

and is 80 km long. There are many more rilles to the north.

Comparing the image above with the NASA image below, from Nambour we see the

area slightly

foreshortened as we are at 27º South while Hadley Rille is at latitude 26º North.

A photograph of Hadley Rille from an Apollo spacecraft, in orbit around the

Moon, cropped to cover the

same area as the previous photograph taken from Nambour, for comparison

purposes. The circle

shows the exact landing site. The camera is looking vertically down, so there is

no foreshortening.

This was the first mission to include an LRV

(lunar roving vehicle).

Theophilus (top),

Cyrillus and Catharina (bottom) were photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour

on July 30, 2017. East (where the Sun is rising) is to the right, north is at the top.

Of these three craters, Theophilus (top) is obviously the newest, for it is

more clearly defined and overlaps

Cyrillus. Catharina is the oldest of the

three, appearing much more degraded and damaged by continual impacts

by small

meteorites over billions of years, All three craters were named by Giovanni Riccioli

in the mid-17th century.

He was a Jesuit priest who knew his history of astronomy and astronomers very well,

and used this knowledge

when applying names to the lunar features. The names

were not chosen at random, and the three above were

named after people connected

with the lost Great Library of Alexandria.

Catharina has a diameter of 100 kilometres and a depth of 3130 metres. It has been damaged by a later impact

on its northern wall, which has produced a 46

kilometre wide crater, Catharina P. The walls of Catharina are

quite steep in places, but the rugged floor is reasonably flat with no large, central

mountains. The floor does

contain some small hills and fissures, and is disrupted in the south by a 16 kilometre crater called Catharina S.

Nearby, on

the southern wall of Catharina, there is a small, bright, bowl-shaped crater 7 kilometres across, Catharina F.

This photograph was taken 23 minutes after the preceding one on July 30, 2017,

which it adjoins. The

crater Catharina is at the top of the image. The Rupes Altai or

Altai Mountains is a 450 km long cliff or

fault escarpment which runs in a huge curve from west of Catharina to the 90 km

crater Piccolomini

at the lower-right corner. The cliff averages 700 to 1000 metres in height,

with some summits approaching

2 km high. One peak is 4 km high.

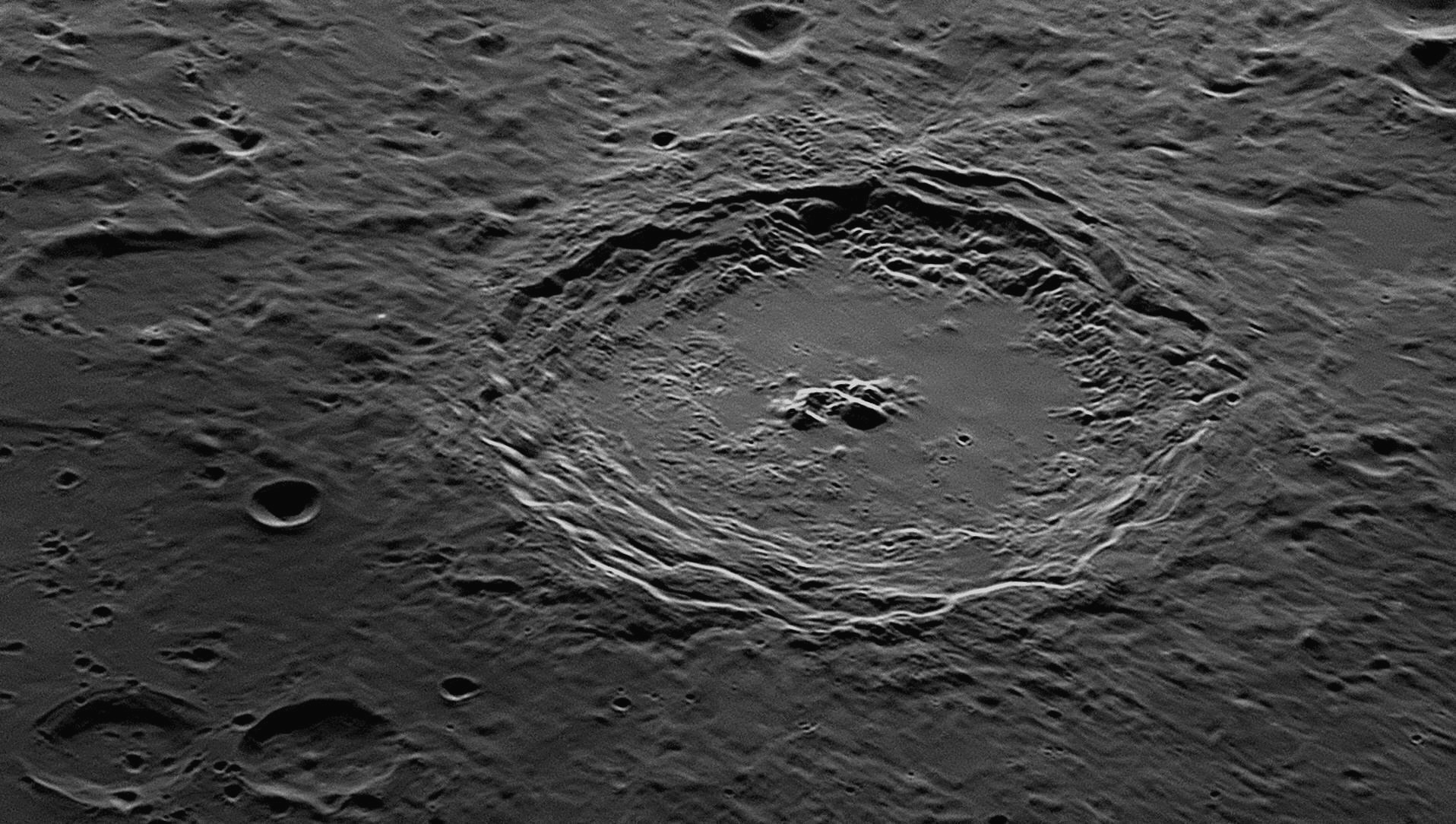

The crater Petavius has a diameter of 182 kilometres and this photograph was taken from Starfield Observatory,

Nambour on September 14, 2018. East (where the Sun is rising) is to the top, north is to the left. As Petavius is near

the south-east limb of the Moon, we see the crater at an angle, which foreshortens its circular shape into an ellipse.

On the southern wall of Petavius (on the right in the picture above, is an 11 kilometre wide crater, Petavius C.

The most spectacular cleft on the Moon runs in a straight line from the central mountain group to the south-west wall.

In this view, the Great Cleft is seen to be relatively shallow in places.

In the foreground is the 60 kilometre wide crater Wrottesley.

A peculiar double ridge 200 kilometres long

passes

through Petavius C and skirts the end of the Great Cleft, terminating near

Wrottesley. Behind Petavius

(to the east)

is the 42 kilometre wide

crater Palitzsch, with the 114 kilometre Vallis Palitzsch (Palitzsch Valley)

running to the

north (left), outside the far

wall of Petavius.

The crater

Langrenus has a diameter of 136 kilometres. Like Petavius above, this photograph was taken

from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on September 14, 2018. The orientation

and foreshortening of Langrenus

is similar to that of Petavius above, for they are near neighbours on the Moon.

The central cluster of

mountain peaks averages one kilometre in height. The north-western area of the

floor is rough, while the

southern half is much smoother. The walls have slumped down to make spectacular

terraces. Outside

the crater, the landscape has been covered with melted rock from the impact.

This image of the south-western margin of the Moon's Mare Fecunditatis (Sea of Fertility) was taken at

5:19 pm on 18 July 2018,

just five minutes after sunset. A deep red filter was used to counteract the light

of the sky. North is to the top, east (where the Sun is

rising) is to the right. The central crater is 77 km

diameter Gutenberg. To its south-east is the 56 km crater Goclenius, which

is crossed by numerous

clefts.

Towards the lower left corner of the image is the 34 km crater Gauldibert, which has a very

unusual volcanic floor. The smallest craterlets clearly visible in this image, e.g. one just north of

the

mountain at the centre of Goclenius, are less than 600 metres across.

Smaller ones in the flat area

due west of Goclenius may also be detected.

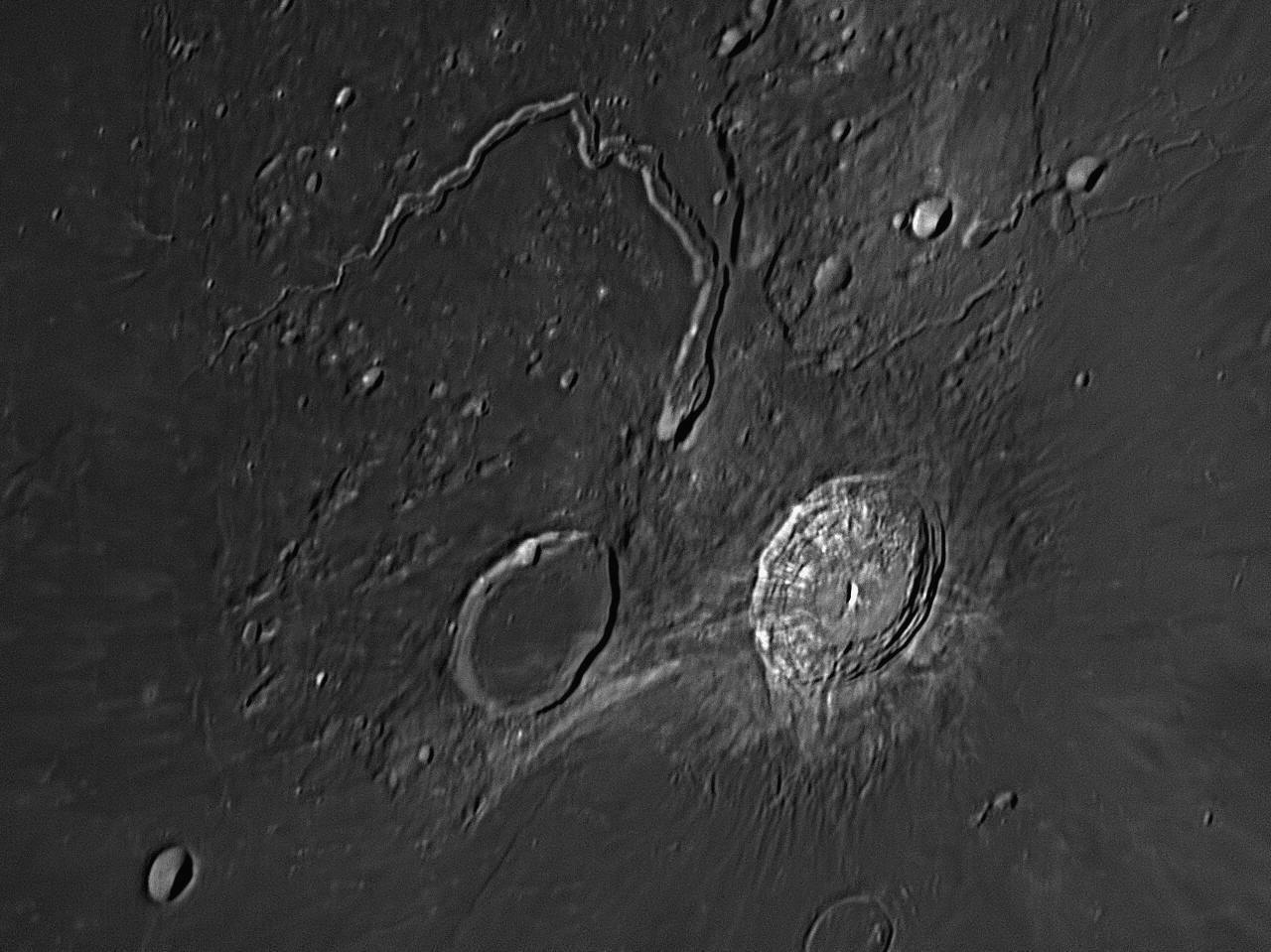

Aristarchus is the bright 41 km crater at right, Herodotus is the

flooded 36 km crater to its left.

Vallis Schöteri (Schröter's Valley) is the remarkable feature to their

north, and is 165 km long. The valley

begins at a small crater in the highlands between Aristarchus

and Herodotus, widens out and then narrows

again heading north, before zig-zagging to the north-west and then turning to the south-west, where it

narrows

further and peters out. It has been described as like a snake, in particular as a cobra, and its widest area

near its starting point has become

known as the 'Cobra Head'. A delicate rille 200 metres wide like a dry

water

course meanders along the valley, visible above for most of its length. There is

a complex of

narrow, winding rilles in the north-eastern corner of this image.

Gassendi was photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on September 2, 2017.

North is to the top,

west is to the left. Gassendi is a moderately large crater, with a diameter of

114 km. It is completely

circular, but due to its position

towards the Moon's west-south-western limb, we see it considerably

foreshortened. It is quite ancient, and since it was formed by the impact of a large meteor or

small asteroid

about 3.9 billion years ago, a large more recent impact has deformed its northern wall (on the right-hand side

in the image above). This later crater is called Gassendi A, and is 33 kilometres across. Almost adjoining

it

on its north-western side is Gassendi B, which is 26 kilometres across. The floor of Gassendi is flat, with

a

group of mountains in the centre that average 1200 metres high. To the south is a large, flat lava plain called

Mare Humorum (the Sea of Humours).

The Mare Humorum was caused by an asteroid striking the Moon in

the epoch after Gassendi was formed.

This huge impact blasted out a crater 391 kilometres

across, fracturing the Moon's crust in the area. These

fractures released pressure on the hot rocky layers below, which immediately liquified, allowing

hot magma

to come to the surface as lava, which filled up the crater that had been formed, resulting in the large,

level

lava plain that was discovered and

named the "Sea" of Humours by Giovanni Riccioli in the mid-17th century.

As the lava spread out from the impact crater, much of it reached the southern wall of Gassendi, sweeping

over it and bursting

in to pool on the southern end of Gassendi's floor (to the left as seen in the image above).

We can see a gap in Gassendi's southern ramparts where the wall

has been completely demolished, and

other parts of the southern wall have been smoothed over by the lava. As the lava cooled, ripples in it became

solid, and

can be seen close to the south and south-east walls of Gassendi. The eastern, northern

and

western walls, unaffected by the lava flow, are rugged.

The three largest

craters above, which once were called ‘walled plains’, are near the centre of

the Moon’s

disc.

Above centre is the large walled

plain, Ptolemæus, which has a diameter of 145 km. Its flat floor

is marked

by numerous craterlets. South of Ptolemæus is another crater plain,

Alphonsus, which is

121 km in diameter and has a central peak protruding from a low 'spine'.

There are a number of ash volcanoes occurring along a cleft system around the

inside rim of Alphonsus.

Each has a dark halo of ash. To the

right of these two large craters is a third, Albategnius,

139 km in diameter.

Adjoining Alphonsus to the south-west is a 41 km crater called Alpetragius,

which has an unusually large domed

mountain at its centre.

South of Alphonsus is a smaller crater with a diameter of 100 km called

Arzachel. It has very steep slopes with

terraces where the walls have slumped. There is an off-centre mountain

mass which rises to a height of 1500 metres.

On the floor is a 10 km crater, Arzachel A. The southern slopes of this crater

are deformed by a later impact

which left a 4 km crater. Another 4 km crater, Arzachel K, is on the floor

slightly to the south of Arzachel A.

A network of rilles curves around the eastern part of Arzachel's floor.

The whole area of this image is damaged

by

material blasted across the surface

by a cataclysmic

explosion called the Imbrium Event. The damage

appears as grooves crossing

the

image

from

north-north-west to south-south-east, and is called 'Imbrium sculpture'.

The photograph was taken on August 1, 2017.

At top centre is the 6 km wide crater

Hyginus. Its northern wall is deformed by a 2 km wide smaller

crater. Passing

through Hyginus is a notable valley or rille, rather disjointed in outline,

appearing

in parts to be made up of chains of collapse craterlets. This area of

the Moon shows numerous

clefts, extending south past the crater Triesnecker at lower centre.

The

south-eastern quadrant of the Moon is covered with overlapping craters ranging

in size from large to

tiny. There are no lava plains (known as "Maria" or "seas" in the area. The two

largest craters in the image

above are Stöfler (left, deformed on its south-eastern rim by Faraday) and

Maurolycus.

Dominating

this area is the

magnificent crater Clavius, 233 km in diameter. The walls rise in places

over

3.6 km above the floor. The slopes at lower right exhibit massive land

slips. A remarkable series

of

five craters begins on the southern wall (top) and

trends in ever-decreasing size towards the north,

then west (right).

The floor of Clavius is covered with numerous craterlets and other delicate

features.

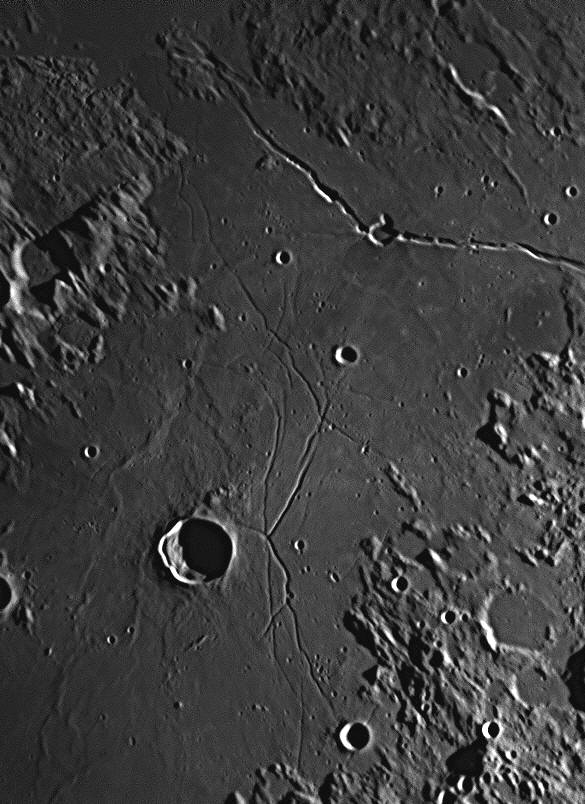

Rupes Recta, or the Straight Wall, is a long cliff in the Moon's Mare Nubium (Sea of Clouds).

100 km

long and 1 to 1.5 kilometres wide, it is a fault scarp.

Despite its appearance under a low Sun as above,

it is neither particularly high

nor steep. The eastern or right-hand side is about 250 metres higher than the

western, near the wall's mid-section. The slope is actually quite gentle,

some sources quoting as little as

seven degrees.

Also in the image are some craters. To the west (left) of the Wall, is the 17 km

crater Birt, the eastern rim

of which is deformed by the later impact that created 6.8 km Birt A. Starting in

a craterlet just to the west

of Birt is a curved rille called Rima Birt, which is 51 km long and turns to the

north-west before fading out.

It has a gap in its middle and a slight S-bend.

The large crater to the right of the image is 60 km Thebit which has a rille on

its floor which is unusual in that

it is composed of four straight sections joined at abrupt angles. Most

rilles are sinuous. Thebit A (20 km)

has deformed the western rim of the larger crater, and is itself deformed by

Thebit L (12 km).

The

largest crater in this image is Pitatus which is 100 km in diameter. To its west

(left) is its 44 km

diameter neighbour Hesiodus.

Both of these craters have flat floors with multiple rilles

around their

circumferences. Pitatus has an off-centre mountain massif on its

floor, while that of Hesiodus has two

newer impact craters, both bowl-shaped.

There is an unusual valley joining the floors of Pitatus and

Hesiodus. A 12 km

'ghost crater', partially submerged by the lava flows from the north, is about

30 km

north of Pitatus, with another to the west. From the western ramparts of

Hesiodus, the 309 km long rille

called Rima Hesiodus runs to the

south-west and off the image. There are three craterlets visible on this

narrow

and shallow valley. They are so well-aligned on the rille that they are probably

volcanic vents associated

with the creation of the rille. It is unlikely that

random impacts from space could have landed together exactly

on the rille.

This image

shows the crater Hesiodus (above centre) when the Sun was higher, reducing the

shadows and flattening

the contrast. Adjoining Hesiodus to the south-south-west

is the 15 km bright crater Hesiodus A. This crater is

remarkable in that it

contains two concentric rings like a bulls-eye. The rings only become visible

when the Sun is

high enough

to shine over the steep walls and illuminate them.

The picture was taken on September 2, 2017.

The rings are only

partially visible

in the larger picture above, which was taken on August 2, 2017.

The crater Tycho is probably the youngest large crater on the Moon. Its diameter

is 88 km and it lies at the centre

of a spectacular system of light-coloured rays. The surroundings are covered

with areas of rock melt and

large angular blocks. The central mountain has three peaks and is 1.5 km high.

Posidonius is a large crater 99 km in diameter with a heavily fractured level

floor. This image was taken

on November 24, 2017. East is to the top, north to the left. There is a secondary rim

of mountains in the

eastern interior. The largest crater

inside Posidonius

has a diameter of 11 km and near

it is a fresh 3 km

crater and some

smaller craterlets.

There are also five

volcanic domes inside Posidonius and three more

outside. Of interest is the

very sinuous

and narrow rille

which starts just inside the northern rim and follows

the rim

to its north-western

curve, where

the rille suddenly turns towards the interior and heads south,

aiming for the

south-western wall.

A branch

turns to the right and heads directly to the western wall (lower

margin in the

image above).

Where the wall

is breached near the bottom margin, shadow reveals that

the floor of Posidonius is higher

than the level of

Mare Serenitatis outside the wall.

This area was photographed from Starfield Observatory, Nambour on May 6,

2017. East (where the Sun

More domes are found about 160 km south-east of Milichius in the area shown

here, which adjoins the one

These domes are only observable when the angle of sunlight is small, i.e.

the Sun is low to

the Moon's

This photograph of the Sinus Iridum (the Bay of Rainbows) and its environs was taken on December 29,

The Sinus Iridum is a very large feature, and is visible with the smallest telescope. It is bounded on the

There is a pair of remarkable impact craters in the south-eastern corner of the image. They are Helicon For the latest

photographs taken from Nambour, click on the

The Stars

is rising) is to the right, north is to the top. The largest crater in the image

above is Milichius, which is a

minor crater only 14 kilometres in

diameter. Milichius is surrounded by a great number of

volcanoes, in

the form of low domes. These are of a roughly circular shape, and

average only 200 to 300 metres high.

At the summit of each one is a volcanic crater, but all appear to be either

dormant or extinct.

Once it was thought that all the craters on the Moon were volcanic in origin,

for that is how craters on the

Earth are generally formed. Not until the

beginning of the 19th century did astronomers become aware

of huge rocky masses

flying through space that could impact the Moon, the Earth and other planets.

These rocks, as big as a truck or as big as Tasmania, were called 'asteroids'

(star-like) by William Herschel,

as in the telescope they are simply points of light, but they are now called

SSSBs (Small Solar System

Bodies) a name they share with comets and meteors.

above it. The largest crater in this image is Hortensius, 15 km in diameter,

towards the lower-left corner

and filled with shadow. There is a fine cluster

of eight domes, most with volcanic vents at their summits,

just north of Hortensius.

Their heights range between 300 and 400 metres. Six of the domes are quite

prominent - the other two a

little more difficult. There are another three domes

elsewhere in the

image - can you find them?

horizon. This produces shadows which reveal the nature of the domes,

which appear as low blisters.

As the Sun rises over the Moon, the shadows

diminish and soon disappear

entirely, the only remaining

features to be observable being the tiny crater vents

at the top of most of them.

These vents rarely exceed

1000 metres in diameter.

2017. North is to the top and west is to the left.

The Bay is a large semi-circular formation in the north-

western part of the Mare Imbrium, (the Sea of Rains).

north-east by the

Promontorium Laplace (Laplace Promontory) and on the south-west by the

Promontorium Heraclides (Heraclides Promontory).

The mountainous western rim of the Bay is

called the Montes Jura or Jura Mountains, named after a range near the Alps, on the border between

France and Switzerland. The Bay is 411 kilometres across. It has been filled with molten lava from the

Imbrium Event about 3.8 billion years ago,

which created the Mare Imbrium. As the lava cooled, waves in its

surface solidified and can be seen in the image above as 'wrinkle ridges', of which

there are more than ten.

The Bay was not completely filled, as its surface is about 600 metres lower than that of the adjoining Mare Imbrium.

(left, 26 km across), and Le Verrier (20 km across). Helicon was a Greek Astronomer who was active around

400 BCE.

Le Verrier was the man "who discovered Neptune by the point of his pen", i.e. by

mathematical

calculation, not by

using a telescope.

Dog Star. It is a very hot A0 type star, larger than

our Sun. It is bright because it is one of our nearest

neighbours, being only 8.6 light years away. The four spikes are caused by the secondary mirror

supports

in the telescope's top end. The faintest stars on this image are of magnitude 15.

To reveal the companion

Sirius B, which is currently 10.4 arcseconds from its

brilliant primary, the photograph below was taken

with a

magnification of 375x, although the atmospheric seeing conditions in the current

heatwave were more

turbulent. The exposure was much shorter to reduce the overpowering glare

from the primary star.

hotter and brighter, its companion Sirius B is very tiny, a white dwarf star nearing the end of its life.

Although small, Sirius B is very dense, having a mass about equal to the Sun's packed into a volume

about the size of the Earth. In other words, a cubic

centimetre of Sirius B would weigh over a tonne.

Sirius B was once as bright as Sirius A, but reached the end of its lifespan on the main sequence

much

earlier, whereupon it swelled into a red giant. Its outer layers were blown away, revealing

the

incandescent core as a white dwarf. All thermonuclear

reactions ended, and no fusion reactions

have been taking place on Sirius B for many millions of years. Over time it will radiate its heat

away

into space,

becoming a black dwarf, dead and cold. Sirius B is 63000 times fainter than

Sirius A.

Sirius B is seen at position angle 62º from Sirius A (roughly east-north-east,

north is at the top), in

the

photograph above which was taken at Nambour on January 31, 2017.

years after Alvan Graham Clark discovered Sirius B in 1862

with a brand new 18.5 inch (47 cm)

telescope made by his father, which was the

largest refractor existing at the time.

Rigel (Beta Orionis, left) is a

binary star which is the seventh brightest star in the night sky. It is huge

when compared with Sirius. Rigel A

is a large

white supergiant which is 500 times brighter than its

small companion, Rigel B.

Yet Rigel B is itself composed or a very close pair of Sun-type stars that

orbit

each other in less than 10 days. Each of the two stars comprising Rigel B is

brighter in absolute

terms than Sirius. The Rigel B pair orbit Rigel

A at the immense distance of 2200 Astronomical Units,

equal to 12 light-days.

(An Astronomical Unit or AU is the distance from the Earth to the Sun.)

Antares, a red supergiant star

The star which we call Antares is a binary system. It is dominated by the great red supergiant

Antares A

which, if it swapped places with our Sun, would enclose all the planets out to Jupiter inside itself.

Antares A is accompanied by the much smaller

Antares B at a distance of between 224 and 529 AU -

the estimates vary. (One AU or Astronomical Unit is the distance of the Earth from the Sun, or about

150

million kilometres.) Antares B is a bluish-white companion, which, although it is dwarfed by its

huge

primary, is actually a main sequence star of type B2.5V,

itself substantially larger and hotter than our

Sun or Sirius. Antares B is difficult to observe as it is less than three arcseconds from Antares A and

is swamped in the

glare of its brilliant neighbour. It can be seen in the picture above, at position angle

277 degrees (almost due west or to the left) of Antares A. Seeing

at the time was about IV on the Antoniadi

Scale, or in other words below fair. Image acquired at Starfield Observatory in Nambour on July 1, 2017.

The red supergiant star Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis) is almost a twin of Antares, but has no companion.

Achernar is the ninth brightest star in the night sky. Its visual magnitude ( mv) is 0.45, and it is a hot

blue-white star of B3 spectral type. The

width of the field is 24 arcminutes and the faintest stars are mv 15.

As it is in the extreme southern sky, it is the only first magnitude

star unknown to the ancient Greeks.

Arcturus, an orange K2 giant star, magnitude -0.05.

Gamma Crucis is a red star at the top of the Southern Cross. It shines at magnitude 1.59, and is a giant

star of type M4. The

white star seen just to lower right of the main star is a sixth magnitude companion,

in orbit around the system's barycentre.

The star Regor, properly called Gamma Velorum. There are at least four stars in the

system. The brightest

star in the image above, Gamma Velorum A, is itself a binary or double star composed of a blue

supergiant

and a massive Wolf-Rayet

star. They are too close to be split optically, being closer than Mercury is to our Sun.

Their double nature is only revealed by examination of their combined

spectrum.

The second component

to its left, Gamma Velorum B, is also a spectroscopic binary, with a period of

less

than two days. The main star in this

pair is a blue-white giant, and it is so close to its companion that the

spectrum of the companion is swamped by the other. Wolf-Rayet stars have strong

emission lines in their

spectra and will end their lives with Type 1b supernova explosions. The one in Gamma Velorum A is one of

the closest supernova

candidates to the Sun. The star's name "Regor" is not ancient nor exotic,

but honours

the Apollo astronaut Roger Chaffee, and is simply 'Roger' spelt

backwards. It was devised by one of the other

astronauts, Virgil "Gus" Grissom, and is not officially approved. It is allowed to be used as both Chaffee and

Grissom, along with the third crew member Ed White, died in the Apollo 1 pre-launch fire in 1967.

The optical double star Mu Scorpii, halfway along the body of Scorpius, is a useful test of keen eyesight,

being only 6 arcminutes apart. Though the two components look similar, it is only a chance alignment,

not a true binary system. The stars are not related in any way. The

upper star of the two is an eclipsing

binary 822 light years distant, while the lower star, a blue-white subgiant, is only 517 light years away.

A typical nebula, where hydrogen gas is condensing into stars. The Great Nebula in Orion, M42, with its

The central section of the Great Nebula in Orion.

Embedded in the centre of the nebula is a multiple star known as the Trapezium.

The Trapezium is composed of four bright white stars, two of which are binary stars with fainter

red

companions, giving a total of six. The hazy background is caused by the cloud of fluorescing hydrogen

comprising the nebula.

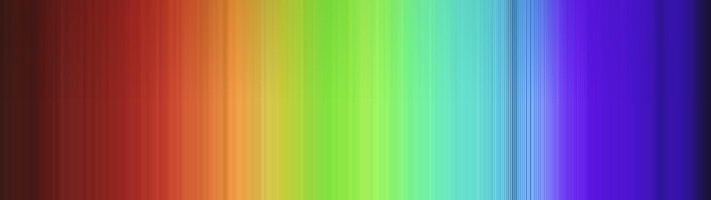

The spectrum

of Vega, an A0

out of a nebula and are of the same age and stage of evolution.

The galactic cluster in Scorpius, M7, is also known as Ptolemy's Cluster.

Ring Nebula - also seen below) are composed of gases such as oxygen and

nitrogen which are fluorescing

from intense stellar radiation from the central

white dwarf star, producing bright-line spectra.

This gives an image of the

circular nebula for each element.

magnitude of 9.7. Photographs taken over a period of 50 years

show the rate of expansion of the nrbula

to be about 1 arcsecond per century, which corresponds to a speed of 20-30 kilometres per second.

M57 is illuminated by a central white

dwarf or ‘planetary nebula nucleus’ (PNN) whose visual magnitude

is 15.75; its mass is approximately 1.2 solar masses. All the interior parts of this nebula have a

blue-

green tinge that is caused to a small extent by the

oxygen emission lines at 495.7 and 500.7 nm. These so-called

‘forbidden lines’ of doubly ionised

oxygen occur only in conditions of very low density where there are only a few atoms per cubic centimetre.

In the outer region of the ring, part of the reddish hue is caused by

the first of the Balmer Series of hydrogen lines. Forbidden lines of ionised nitrogen

( N

reddish colour at wavelengths of 654.8

and 658.3 nm. Each of these emission lines reveals itself as an image

of the

whole nebula. The three brightest ones are easily seen, but there are three more

very faint ones visible.

The Ring Nebula, M57, a planetary nebula.

A planetary nebula, the 'Ghost of Jupiter', NGC 3242, formed when the central star exploded.

The 'Wishing Well Cluster', NGC 3532.

The Eagle Nebula, M16, a star-forming area.

This nebula has almost entirely contracted to form a cluster of new, hot, blue stars. Small amounts of wispy

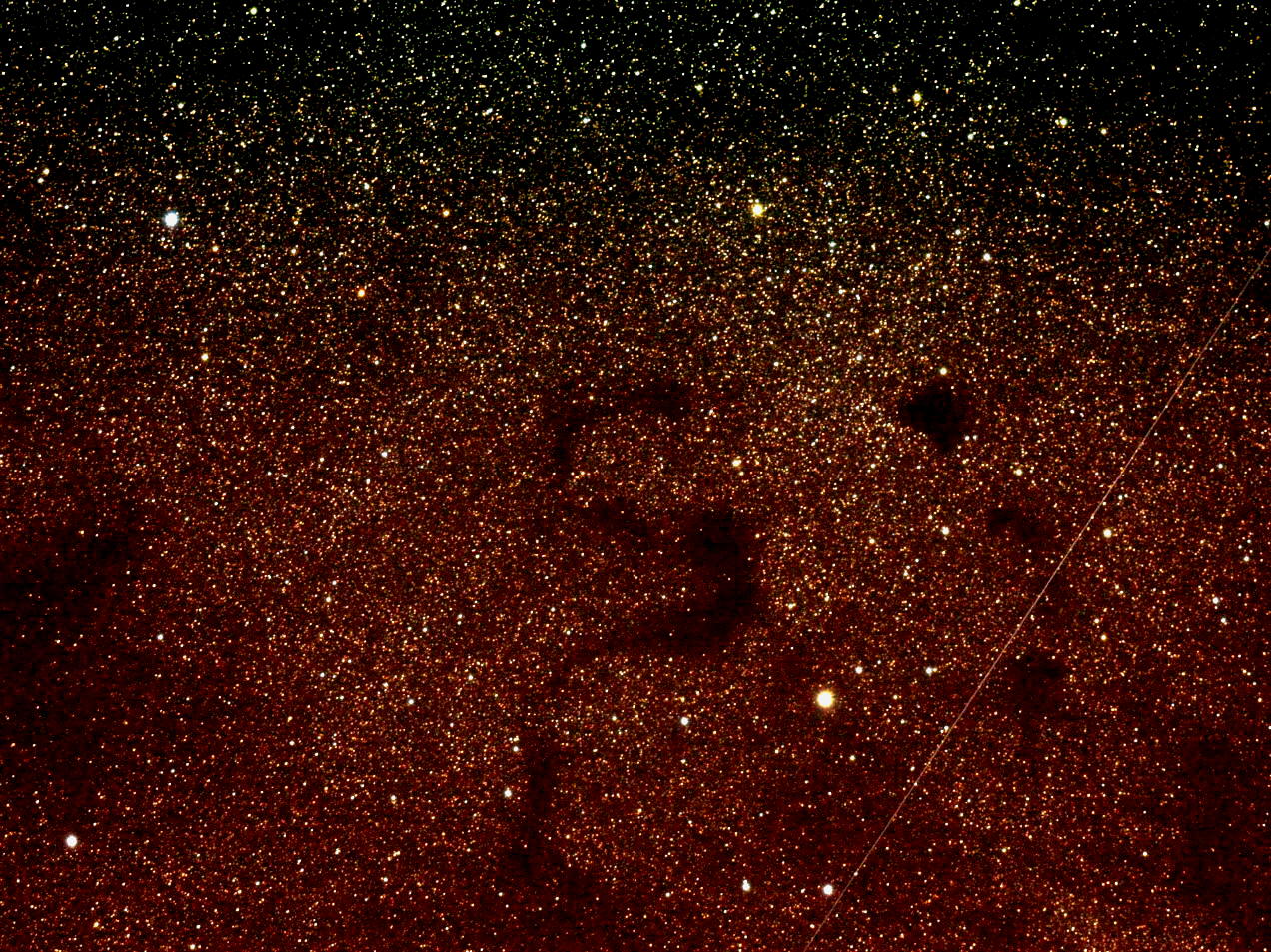

Star clouds in Sagittarius, with the dark Snake Nebula obscuring the stars behind. A satellite trail crosses the image.

The cluster IC 2602, known as the 'Southern Pleiades'.

The central core of Omega Centauri

There are over 120 globular clusters like this one, on the outer fringes of our

galaxy. They contain hundreds

of thousands of old stars. This example is named NGC104, but is popularly known as 47 Tucanae.

The globular cluster NGC 6752 in the constellation Pavo.

star to the Sun. It orbits the bright binary star Alpha Centauri (at left).

The binary star at the centre of the Alpha Centauri triple system. Both stars are solar types.

The binary star Albireo (Beta Cygni), which is well known for its colour contrast.

of fluorescing hydrogen

The Keyhole, a dark cloud obscuring part of the Eta Carinae Nebula

The Homunculus, a tiny planetary nebula ejected by the eruptive variable star, Eta Carinae

The Cat's Paw Nebula

The star Zeta Scorpii and the open cluster Caldwell 76.

The Dumbbell Nebula, M27

The centre of the Lagoon Nebula

Nebulosity in Scorpius.

The two bright stars at centre form the sting of the Scorpion's tail. Their names are Shaula and Lesath.

Shaula and Lesath are both hot, blue B type stars.

This cluster of new, hot B type stars surrounds the star Theta Carinae, and is sometimes called the

'Southern

Pleiades'.

Halley's Comet, photographed as it passed in front of the stars of Scorpius in April, 1986.

The Great Spiral M33 in Triangulum.

The Great Galaxy in Andromeda, M31, photographed at Starfield Observatory with an off-the-shelf digital

camera on 16 November 2007.

one sixth of the way to the edge of

the universe. It is 1000 times further away than the Andromeda Galaxy

shown above.