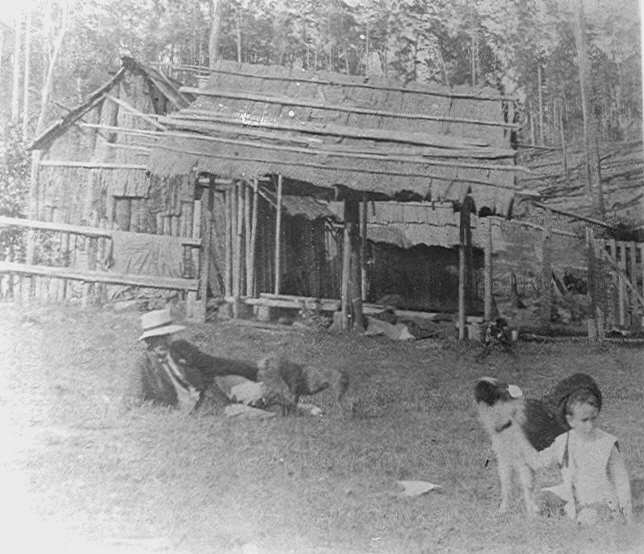

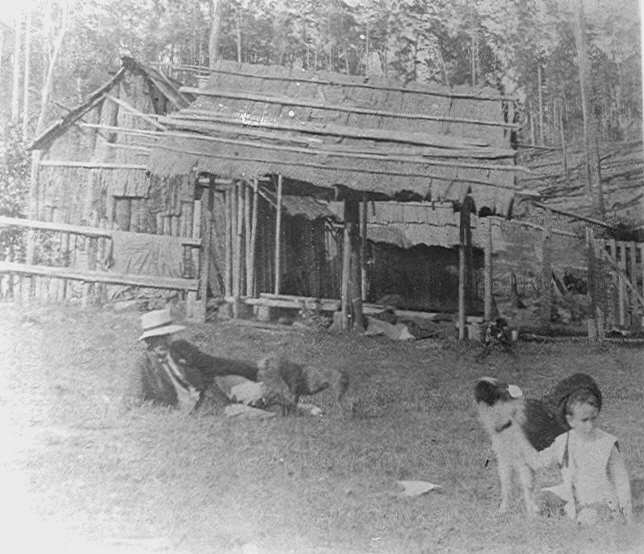

Henry Tucker's house in 1900, a typical pioneer's slab hut

The

beginnings of Mapleton

In 1889 the promise of the Blackall Range region came

to the notice of two young farmers, who were then working for their father as

market gardeners on their fruit and vegetable farm at Redland Bay, on the

outskirts of Brisbane. William James Smith, aged 21, and his brother Thomas

David Smith, 20, had emigrated from England to America with their parents

before moving on to Australia. Their sister Amy had been born while the family

were living in the United States. The Smith brothers had heard that some newly

surveyed land on the Range, nine miles west of Petrie's Creek, was available

for selection, so they set out that September to inspect it with a view to

settling there and growing bananas.

From their home in Redland Bay, they travelled by

train to Brisbane and then to Caboolture, which was the terminus of the North

Coast Railway at that time. There they boarded a Cobb & Co. stagecoach at

4.00 p.m. for a bumpy overnight ride to the Cobb's Camp Hotel where they

arrived at 6.00 a.m. the following morning in time for breakfast. That morning

they continued by coach over Currie's Knob to Matthew Carroll's Hotel on

the corner of the Bli Bli Road. The only other building in what was to become

the town of Nambour was a rough slab hut, occupied by Thomas Howard.

A cattle station homestead was located on a nearby

ridge. Only two other people lived in the area between the homestead and the

Range, James Stark near Highworth and John Murtagh at Doolong. Both men were

timber cutters, and had made many tracks into the scrub to enable them to

bring out logs.

Carrying heavy swags, the Smith brothers sought out

Thomas Howard, who led them up the hills of the Nambour cattle-run and over

the Highworth Range. A road had been surveyed, but it had not yet been built.

With care, they were able to find the occasional blazed tree which confirmed

that they were heading in the right direction. The men found that the area was

covered with thick rain forest containing large quantities of red cedar, beech

and pine, all tangled up with a mass of vines. Soon they reached the area now known as Kureelpa.

There they met James Stark who took them along the rough timber tracks that

criss-crossed the scrub to where John Murtagh was working, and there they

spent the night.

The next morning, with John Murtagh acting as a guide and accompanied by Mr Stark, they climbed up the Range to inspect the newly surveyed blocks that they had heard about. It took all day to cover the three miles along snigging tracks through Doolong to the foot of the Range, and then to force their way through thick scrub to the top. Once there, they found that the only tracks through the vine scrub were those cut by the surveyors, so they followed these to find the corner pegs of the few blocks that had been marked out. The brothers returned to Petrie's Creek, where they were able to obtain a tent, axes, brush hooks and food. They carried these supplies back up the Range and set about 'staking their claim.'

William Smith selected an area of 160 acres near the present Falls Road, that had not been previously surveyed. He pegged it out himself, and lodged his application for an agricultural farm with the Department of Lands on 30th October 1889. Within three weeks his brother, Thomas had lodged an application for another unsurveyed 160 acre block along the western edge of the Range near a stream that broke over a steep rockface in an impressive waterfall (now known as the Mapleton Falls).

After spending

some time looking over other blocks of land available on the Range, William

found some land that he liked better than the block he had applied for. After

some correspondence with the Department of Lands, William

forfeited his original selection and made a fresh application on 2nd August

1890. This new selection covered the area of the present Rainbow Park Drive,

north of Post Office Road. Mr David Smith, father of William and Thomas,

agreed to take over William's previous claim, but remained living at Redland

Bay.

These blocks were later surveyed properly with a theodolite by a Government

surveyor, David Smith's farm being measured out by Mr Alfred Lymburner in

April 1893. (Lymburner was a close relative of Alfred Delisser, who had been the

first surveyor to visit the area ten years before.)

The first task facing the Smith brothers was to cut a

walking track from their blocks to the top of the Range and then down its

steep slopes to the timber track below. The actual route that they took is not

known with certainty, but it is likely that they followed a blazed line which

had been surveyed between Nambour and the Mt Ubi cattle station. This went

straight down the escarpment from the north-east corner of today's Mapleton

State School reserve,

and linked up with an official road surveyed (but not built) between Nambour

and Doolong (now Sherwell) Road.

The track was narrow, steep, slippery, boggy and

dangerous but it was the track along which the Smith brothers walked every

week to carry supplies of food, necessities and tools from the boats at

Petrie's Creek and, after the railway was opened early in 1891, from

Nambour. Each trip to Nambour and back meant a walk of eighteen miles.

Clearing

the land

The next task was to clear their claims, and they

engaged two timber cutters to cut down the high trees. As the branches were so

entwined and the trees linked with vines, many trees would not fall separately

when cut. The method adopted by the scrub cutters was to cut almost through

the trunks of a large number of trees at once, leaving key trees uncut, about

a quarter of an acre at a time. The key trees would then be cut, sometimes

dynamited, and the whole lot would fall together. This was called a 'timber

drive', and was especially successful in clearing tree-covered slopes.

They felled twenty acres of vine scrub and, when it

was dry, they 'burnt off'' with a roaring fire that poured heavy clouds of smoke over the Range and left behind a blackened mass of logs and

stumps. After two months enough land was cleared to enable farming to begin.

Henry Tucker's house in 1900, a typical pioneer's slab hut

The first

farms

The Smith brothers built the first slab hut at

Mapleton in 1890. They cleared a small area, felled a hardwood tree, split

slabs and shingles and built a two-room hut with slab walls, a shingle roof,

and a flag-stone floor. This was on Thomas Smith's selection on the way to

the Falls. Their sister Amy came up and kept house for them for over two years

before marrying a new arrival, Mr David Williams.

The two brothers worked together and cleared areas on

their separate selections. They were in their early twenties and worked hard

from dawn until dark. They sowed grass seed in one section to make a paddock

for horses, and with their

mattocks they dug holes and planted bananas, maize,

sweet potatoes, pumpkins, tomatoes and other crops. Gooseberries sprang up

everywhere and produced prolific yields.

Acting on previous experience, the brothers decided

to plant bananas, and a block of thirty acres was prepared. The first

consignment of banana suckers was obtained from their parents' farm at

Redland Bay. They were first carted to Cleveland, then carried by rail to

Woolloongabba, by Pettigrew's steamer S.S.

Tarshaw to Maroochy Heads, by Histead's punt up Petrie's Creek to

Davis' Pocket, by bullock wagon up the rough logging tracks to the top of

the Range and by horse-drawn slide to Thomas Smith's property.

It took six weeks to transport the banana suckers

from Redland Bay to the Blackall Range and the cost was 7 pounds per hundred. After twelve months there was a magnificent

crop. Bunches of bananas were ready for market and the problem was how to

transport the fruit to the railway station at Woombye. The narrow tracks made

a vehicle out of the question. The Smith brothers purchased five pack-horses

and used them to carry two cases of bananas each, one on either side of the

pack-saddle, or three bunches each.

It was a day's work for a man to take five

pack-horses carrying ten cases of bananas from the Range to Woombye or, after

January 1891, the new Nambour station. Often the track was so wet that the

horses became bogged and had to be unloaded before they could be freed. Unfortunately there was a glut of bananas at the time, due to a

record

local crop. They realised only 2d. (2 cents) per dozen on the Brisbane market,

which was a very meagre return for all the work involved.

As the number of banana growers

increased, it became the custom to cut the fruit on certain days, and for the

men with their pack-horses to meet at 'The Box Tree' at the top of the

Range (a large tree near the site of the present-day Mapleton Tavernl), where a long

string of pack-horses would be made up. Horses and owners then journeyed down

to the railway to despatch their fruit.

Drought and flood

The Smith brothers had only

just felled and burnt their first area of scrub, planted their first bananas and

sowed an area with grass seed when in 1890-91 a severe drought scourged the

district. Surface water dried away and the creek that tumbled over the Falls

almost ceased to flow, due to the massive scrub timbers along the banks draining

the supply. The two brothers feared that they would have to leave their

selections and return to Redland Bay.

One day when Thomas Smith was

clearing land he noticed moist earth near the stump of a gum tree that he had

felled. The two brothers dug down to make a well. They split slabs and

shored up the sides of the hole to prevent any collapse of the wet soil. With round timber

they made a windlass. Using a technique known to the Aborigines, lengths of

lawyer vine up to twenty feet long were cut down, and the hard, rough outer skin

peeled off. The strong and supple rope resulting was just as strong as a hemp

rope. They joined lengths together, fastened them to the windlass, and lowered a

metal drum as a bucket to remove the earth. They travelled up

and down standing in the drum, suspended by three or four strands of lawyer

vine. At a depth of

fifty feet they found sufficient water for their needs. Those were the days when courageous, resourceful men with a will to

succeed used the primitive means at their disposal to achieve their purpose.

Lawyer vines were known to the Aborigines as Yura. They were long, tough, strong vines that grew in abundance, entwining the tops of trees. They had prickly fronds and long, tough tendrils with thorns like sharp-pointed teeth sloping backwards. Because of the tearing effect on clothing and bare skin, the lawyer vine became known as the 'wait-a-bit'. It is still known locally by this name and as the 'wait-a-while'.

The drought was followed by the

disastrous 1892-93 floods, which caused great havoc in south-east Queensland.

The Crohamhurst Observatory near Peachester reported that 107.6 inches of rain

had fallen in the 27 days up to 2nd February 1893, an average of four inches of

rain every day for a month. The settlers on the Range were unable to leave the

mountain top, and so could not get down to Nambour to obtain food supplies. In any case, Nambour was in

much the same predicament, as the railway and boats could not get through

because of widespread flooding. The resourceful women of the Range overcame this

difficulty by drying bananas and grinding them into banana meal. They used the

meal to provide sustenance until the track to Nambour became passable once more.

Strawberries

Owing to the small profit in

selling bananas and the difficulty of transport, the settlers soon decided to

try a crop that could be more easily packed and carried, and that had a higher

return. Accordingly, many acres of strawberries were planted which, in time,

gave a prolific yield. The marketing of the berries entailed a lot of work.

After picking the strawberries and placing them into specially made containers,

they were then graded. Prime fruit would be packed into fern-lined, home-made

pine trays, and the smaller berries stemmed and put into wooden kegs for the jam

market. These were transported by pack-horses down to the Nambour Railway

Station. Growers received a remarkably good return, obtaining one shilling (10

cents) per quart on rail at Nambour for the markets of Sydney and Melbourne.

Also, the Cape gooseberries

that were appearing everywhere produced abundant crops. These were picked during

the day and husked at night, the people working into the early hours of the

morning. The berries were packed in fifty-six pound casks and sent to Brisbane

for jam manufacture. The strawberries though, turned out to be merely a 'stop-gap' crop

after bananas went out and until the citrus trees came into bearing.

To help with money, the Smith brothers took a

contract with the Maroochy Divisional Board to fell timber to the width of one

chain and clear stumps and logs for a wider track down the Range. The payment

was three shillings (thirty cents) per chain, and this worked out at three

shillings per day in return for fifty-five hours labour per week. Payment for

scrub felling in those early days was three shillings per acre. William and

Thomas did this work while waiting for their crops to mature. It is recorded

that, after working all day on the road, Thomas Smith would hang a lantern on a

forked stick after his evening meal, and dig rows to plant strawberries.

On 21st October 1891, David

Smith's wife Emma, mother of William and Thomas, passed away. Soon after,

David decided to join his sons, and drove by horse and cart from Redland Bay,

along the Gympie Road to Nambour and then with great difficulty up the narrow

track climbing the steep hills to Mapleton. The journey took him a week, and he

settled on his block along the Mapleton Falls Road.

Citrus orchards

Around 1892, a Mr Benson, an agriculturalist who later became Director of Fruit Culture, visited the district. He strongly advocated the planting of citrus trees, particularly oranges and mandarins. Acting on his advice, David Smith planted an orange orchard, and it flourished. Finding that he had enough trees to provide a very handsome income, he decided not to undertake the clearing of his remaining land but subdivided the acreage into twenty small farms, selling blocks of twelve to fifteen acres to five other settlers.

Gradually the citrus orchards, which were later to make Mapleton famous, were established. William and Thomas Smith both laid out splendid orchards, as did many other settlers. Many of the first seedlings were obtained from Joseph Dixon's orchard at Flaxton. Mapleton quickly became a leading citrus producing area, the most popular trees being orange trees. The Mapleton crop matured one month later than other citrus areas, which was an advantage towards the end of the season. The orchards produced an excellent livelihood for many families. The soil was so fertile that a mature orange tree could produce over twenty cases of oranges in a season, with a return of nine shillings per case.

It was said in 1909 that an

acre of ground planted with mature citrus trees could yield 60 - 70 pounds cash per

annum, at a time when a worker's average yearly income was less than 100 pounds.

But the success of the orchardists pushed up the cost of land. Compared with a

purchase price of 46 shillings per acre in 1889, by 1909 prime land was changing

hands at 80 pounds per acre, nearly 35 times as much.